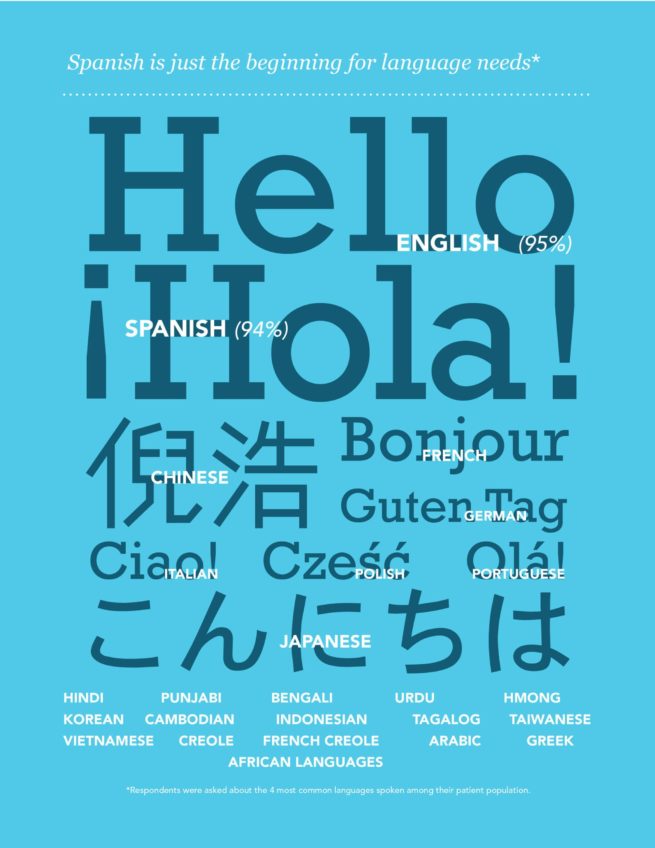

Language barriers remain the biggest obstacle to serving culturally diverse patient populations, researchers say. Almost half of the healthcare providers surveyed for a recent study told researchers from HealthEd Academy that they lack access to patient-education materials in appropriate languages. Chinese-language and Spanish/Spanish Creole materials seemed to be in shortest supply, with each garnering most-needed status by 18% of respondents.

The survey of 192 healthcare extenders (any Non-MD HCP) was conducted in late 2012. The aim was to gauge the pulse of education for culturally diverse patients. Findings have been published in the report, “Engaging Patients from Multicultural Backgrounds: providing culturally competent care in a diverse society,” released Monday.

Findings come on the heels of a previous HealthEd study that showed most health educators rely primarily on paper-based education when talking with patients, which has implications for pharma marketers providing such materials through digital means. The new report also has important ramifications.

Researchers say that providing sound and accessible education to diverse patient groups is of growing importance due to the convergence of three factors: changing demographics, a disparate healthcare system and the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

This leaves HCEs at the frontlines, often with very little support. “They’re an overlooked group, but they’re the group that interacts the most with patients,” said Katherine Margolis, PhD, director, health behavior strategy and research, HealthEd. “Healthcare Extenders often have a lot of knowledge, and a lot of things they want to be doing, but a lot of time they lack the resources. [This report shows] that they’re raising their hand and asking for help.”

Respondents (29%) cited language barriers and lack of understanding of cultural beliefs as the primary challenges to effective communication with culturally diverse patient groups. Those two challenges, which handicap an already bereft group, can be costly: patients with limited proficiency in English are also less adherent to treatments, less satisfied with their care and more likely to be confused with their treatment plan, according to HealthEd.

To eliminate that confusion, HealthEd Academy recommends trying to bring patients into the fold when developing materials. They note that one in three healthcare extenders develops his or her own patient-education materials (42% do their own translation into other languages). That is an important first step, but they typically involve other HCPs to develop these materials, as more than half say they “seldom or never involve patients, community stakeholders, or care partners.”

Print too has shown prevalence among culturally diverse groups. Nearly 30% of HCEs polled said “they do not use technology or social to engage patients—or they do not see the benefit in doing so,” and most patient education continues to come in the form of print (85%) and in-person (88%).

But Margolis told MM&M that a one-size-fits-all solution remains unlikely: “It’s going to be a multi-channel approach. It depends on your population. It’s really a matter of knowing how they want to be contacted.”

Chinese and Spanish Creole were the most requested language for new education materials. While the report suggests that expanding materials to other languages is vital for better communication, there needs to be a consulting team in place from the start, says Margolis: “It’s a matter of forming a panel that they can consult with and run their opinion by, especially if they’re developing their own materials.”

For those who need help tailoring their own materials, the report provides a tool kit with the following framework: learn more about your audience, plan ahead for development, involve patients in the process, expand resources to multiple languages and seek feedback at each stage.