A recent study by the National Survey for Children’s Health (NSCH) found that ADHD prevalence continued to climb upward from 2007 to 2011. The study’s findings, which appeared in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, show a 42% increase in parent-reported diagnoses among school-aged children during that four-year period.

The disorder also seems to skew more toward boys than girls. Researchers found that 20% of 11-year-old boys had been diagnosed with the disorder at some point in their lifetime and were 125% more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD.

However, even when children are diagnosed, only 30% are adhering to their treatment plan, the study showed, and one out of every five children diagnosed is not taking his or her medication or receiving counseling.

Researchers surmised that “efforts to further understand ADHD diagnostic and treatment patterns are warranted,” and warned of the “increased burden of ADHD on the healthcare system.” The survey concluded that, based on researcher estimates, the “cross-sector costs associated with ADHD likely exceed the previously estimated upper bound of $78 billion.”

That ceiling was determined in the study, “Economic Impact of Childhood and Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in the United States,” which appeared in the Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry in 2012.

An effort to further understand ADHD diagnostic and treatment patterns is already underway by a few companies that have developed diagnostic tools—albeit ones aimed more at curbing abuse in young adults rather than children.

Publishing company Pearson presented results from its Quotient ADHD test at the US Psychiatric and Mental Health Congress this past October. The test tracks motion and measures shifts in attention to give healthcare providers an “objective picture of the core symptom areas of ADHD,” the company said in a statement.

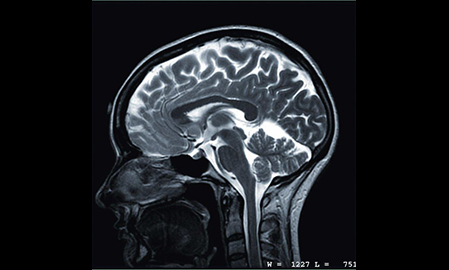

And this past summer Augusta, Georgia-based startup NEBA Health was given approval for its device that scans brain waves. But using the NEBA comes at no small cost, $300 a pop, and insurers have been reluctant to cover the test.

If the economic burden of ADHD continues to climb, these tools may become a popular route to determine who’s suffering and who’s simply not trying. The availability of more demonstrable criteria than industry-standard patient interviews could be too promising for physicians to pass up.