Two targeted cancer pills that received the FDA’s nod yesterday offer physicians another set of weapons to fight the disease. They also highlight a difficulty that has plagued recent advances—the body’s resistance to personalized drugs.

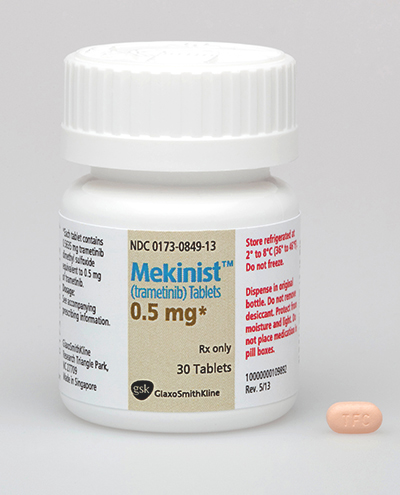

GlaxoSmithKline’s Tafinlar (dabrafenib) and Mekinist (trametinib) were sanctioned for use as single-agent oral therapies in treating unresectable or metastatic melanoma.

Tafinlar got the OK to treat patients with melanoma whose tumors express the BRAF V600E gene mutation. It’s in the same class as Roche/Genentech’s Zelboraf, the initial BRAF inhibitor to reach market. Mekinist, the first drug in a new class called MEK inhibitors, is cleared to treat patients whose tumors express the BRAF V600E or V600K gene mutations.

That gives the two new treatments a pre-defined patient population. Approximately half of melanomas arising in the skin have a BRAF gene mutation, the FDA said.

The approvals add to the excitement going into the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting, which gets under way tomorrow in Chicago. However, they also underscore a difficulty. As drug makers advance in identifying targeted therapies for particular biomarker segments, in many cases where they’ve developed such a treatment, the cancer comes back months later.

Scientists are realizing that “targeted therapies do not lead to long-term tumor control,” said Richard Wagner, PhD, a VP at Kantar Health. “This is a problem that shadows progress.”

One example is Zelboraf, the drug approved in 2011 which targets the roughly 50% of melanoma patients whose tumors carry the BRAF gene mutation. In virtually all of these patients, the tumor starts to progress again in about five months.

In another case, ALK-positive patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), tumors are held at bay for about nine months after those with the mutation take Pfizer’s Xalkori (crizotinib). One of the ASCO presentations will explore data for Novartis ALK inhibitor LDK378, which appears to be the first drug able to deal with the issue of short-lived response.

In a Phase I study of 123 NSCLC patients, tumors in 70% of the patients evaluated responded to the drug, and overall, tumors hadn’t progressed for a median 8.6 months. That’s encouraging for lung cancer patients, particularly those who relapse after crizotinib.

In melanoma, it was thought that combining GSK’s Mekinist with a BRAF inhibitor like Zelboraf or Tafinlar could delay progression. Tafinlar and Mekinist were approved as single agents, though, not as a combination treatment.

GSK is testing the two together in a Phase III study called COMBI-AD, but it’s not clear whether combined use is better than using any two melanoma drugs in sequence, Wagner said. Moreover, a statement from GSK notes that Mekinist has a specific limitation of use in patients after a BRAF inhibitor, something payers could use to deny coverage.

Use of a second targeted therapy after the first could become the standard of treatment in melanoma patients whose tumors express the BRAF mutation, however, there needs to be more support from academic physicians and guideline committees before it’s accepted as standard of practice, added Wagner.

Meanwhile, the two GSK drugs could be left competing with Zelboraf for first-line usage. “[GSK has] succeeded in getting both drugs to market with a first-line label,” said Wagner, “but this problem of resistance of a total treatment strategy for the BRAF-mutation patients is unanswered.”

Not every tumor where breakthrough treatments have been put forward develops resistance. Exceptions include the BCR-ABL inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia (Novartis’ Gleevec and Tasigna, Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Sprycel).

But trying to find ways to prevent the development of resistance with targeted therapies has become another front in the war on cancer. It’s also among the reasons why there is so much excitement about the immuno-oncology agents from BMS (nivolumab), Merck (MK-3475) and Roche (MPDL3280) that offer a third approach to treating the disease, beyond targeted therapies and conventional chemotherapy.

“We’ve [seen] impressive activity in multiple tumor types, long-lasting and durable results, as well as very good tolerability,” said Mike King, an analyst with JMP Securities, of those agents, also known as the “programmed death,” or PD-1 and PD-L1 therapies.

Speaking as part of a panel assembled by Kantar Health, King said that what he thinks is compelling about the experimental agents is the “ability to get treated for a year and walk away for three to five years.”

Both the GSK drugs were approved with a genetic test called the THxID BRAF test, a companion diagnostic that will help determine if a patient’s melanoma cells have the V600E or V600K mutation in the BRAF gene. It’s sold by bioMerieux.