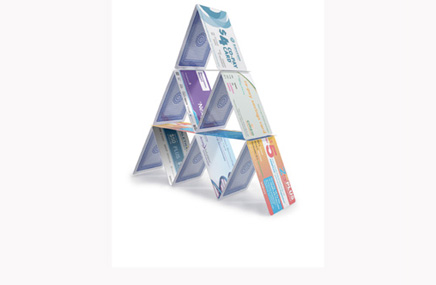

Co-pay cards have proliferated, undermining payer benefit plans. Now, insurers are striking back against the cards. Larry Blandford on what defensive measures plans are taking and what pharma can do to preserve one of its most effective marketing strategies

Over the past few years, co-pay cards have become an increasingly popular strategy used by manufacturers to support use of their products. Many co-pay card programs are designed to increase the affordability of certain therapies and to reinforce adherence. According to Richard Evans, a health analyst for Sector and Sovereign Research, co-pay assistance is now available for nearly half of the top 100 prescription drugs sold in the US.

The trend, however, has not been without implications. Some health plans and employers feel that discount programs that include co-pay cards have been designed to discourage patients from using less-expensive generic drugs, and instead direct them toward more expensive branded therapies.

Co-pay cards are designed to offset the cost share for patients as part of their prescription coverage, which has nearly doubled over the last 10 years according to a recent report from the Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research & Educational Trust. Although some studies have attempted to quantify the effect of increased co-pays on prescription adherence, the results have been mixed.

However, pharma companies realize that patients are less likely to fill a more expensive prescription, either to initiate or continue therapy. Thus, offering co-pay cards allows providers and patients more treatment options and enables them to choose or continue a prescription without co-pays being a significant factor.

Many forms, different goals

Strategies for consumer co-pay cards vary with respect to the amount a given card supports, as well as the alignment to the product’s life cycle. For example, Pfizer has initiated a co-pay program for Lipitor, one of the most successful drugs in existence for most of its life cycle and now available in a generic formulation. As a result, Pfizer now offers a $4 co-pay card for Lipitor in an effort to continue patients on its branded statin therapy. Given that some patients have been taking Lipitor for an extended period, the goal is to reinforce adherence to a single prescription in order to help more patients reach their lipid goals.

Although many co-pay cards focus on reducing a patient’s co-pay for a single prescription, others have the effect of changing the way the drug is purchased altogether. Some co-pay cards are valid for all co-pay costs for as long as a year. When used in this manner, co-pay cards effectively “buy down” a drug’s co-pay tier status, working to create a greater sense of loyalty to the brand. UCB’s Cimzia, for Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis, offers a co-pay card that provides 12 months of therapy with no out-of-pocket costs, regardless of a patient’s insurance status.

Co-pay cards also provide valuable support for newly approved drugs trying to gain a foothold in the marketplace. One example is Novartis’ once-daily multiple sclerosis drug Gilenya, which costs approximately $48,000 per year. Through the Gilenya co-pay card, patients may be covered for up to $800 per prescription and up to $10,400 per year.

Payers strike back

Although the uptake of co-pay card programs is seen as a success by pharma, the resulting impact on payers has not been positive. When patients use co-pay cards to offset their cost share, the payer is then responsible for the remaining cost, resulting in higher-than-expected costs for the plan. Some payers have seen their pharmaceutical benefit costs increase by more than 25% because of discount programs and co-pay coupons.

This is because co-pay cards can undermine a payer’s ability to stratify co-pay amounts to reduce drug costs. The cost to payers can increase dramatically if members choose a branded drug when a less expensive generic is available.

Not surprisingly, plans have taken measures to thwart the continued emergence of co-pay cards while still appealing to members. CVS Caremark provides comprehensive drug coverage to more than 2,000 health plan sponsors and participants throughout the US and Puerto Rico and operates a national retail pharmacy network including more than 57,000 participating pharmacies. Last fall, CVS Caremark proposed recommendations to its clients to no longer cover 34 drugs in 2012. Close to half of these drugs also have active co-pay card programs in place, including GlaxoSmithKline’s erectile dysfunction therapy Levitra and Eli Lilly’s insulin therapies Humulin and Humalog.

Another defensive tactic in use is adding step-therapy edits, which require patients to have tried another preferred product, like a generic, before allowing coverage. This tactic attracted attention in early 2011 after The New York Times noted a health plan in New York state had employed the strategy after noticing costs for an expensive acne drug, Medicis’ Solodyn, were being driven up by use of a card distributed by the drugmaker that reduced patients’ out-of-pocket costs sharply.

As pharma continues to roll out more co-pay card programs, payers can be expected to continue to adopt tactics that help deflect the impact the cards can have on their bottom line. Step therapy is likely to increasingly become a part of plan design for products with co-pay cards, as are NDC (National Drug Code) blocks, where the product is not covered at all.

At the same time, implications of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act allow patients to have more freedom choosing their health plan, resulting in pressure on plans to retain these members. Drug costs will be an important consideration that pharma companies and payers will have to keep in mind when designing and selling prescription drug coverage. However, it’s important to note that federal programs such as Medicare and Medicaid do not accept co-pay cards.

Pharma strategies

Moving forward, pharmaceutical companies and payers will likely have to pursue ways to reconcile their approaches. While manufacturers will likely continue to offer co-pay card programs, they may target their use and possibly negotiate with payers to reach co-pay card offerings that prevent product blocks.

Possible strategies may include targeting particular patient types, being aligned with preferred products, and supporting adherence initiatives. Since medication adherence is growing as an important quality measure as evidenced by inclusion of these metrics in the current Medicare Five-Star Rating System, this is a natural alignment that could benefit all.

Coordination of efforts to ensure that patients receive the best possible care in a financially responsible manner will be an important part of moving toward the larger goal of providing therapies that patients will be willing and able to pay for. This ultimately will better meet patient needs. Whether payers and pharmaceutical companies find this common ground or remain disconnected remains to be seen.

Larry Blandford is SVP, strategic services, for The Hobart Group.

From the March 01, 2012 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media