Patient navigators aren’t exactly a new phenomenon. First introduced in 1990 to guide cancer patients through the oncology maze, they’ve steadily surged in popularity in areas as diverse as mental health, fetal medicine and cardiac rehab.

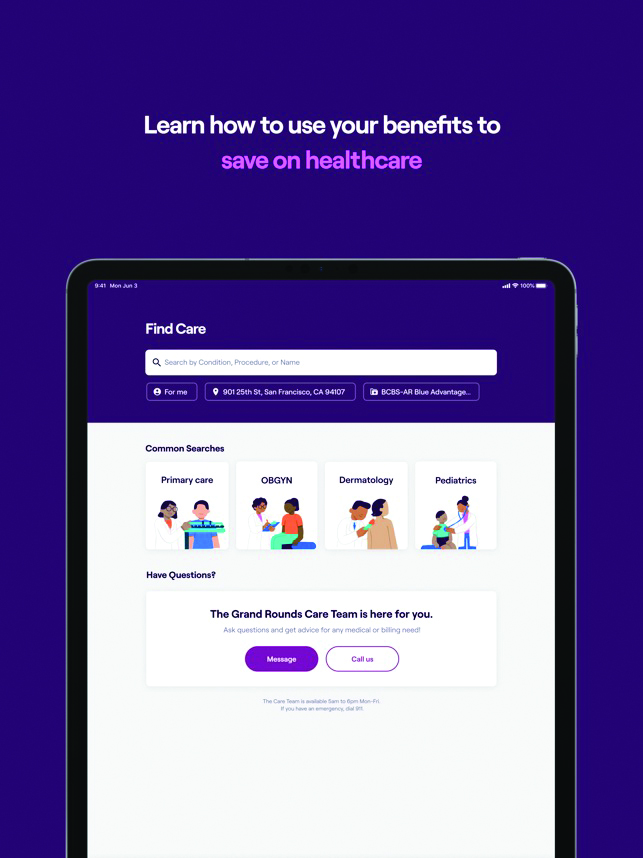

But thanks to a perfect cocktail of trends — notably the rising complexity of the healthcare system, new awareness of treatment disparities and more involved digital tools — navigation programs have finally moved into the medical mainstream. In addition to programs engineered by providers, patient navigation experts such as Grand Rounds, Accolade and Included Health have stepped up to help patients manage the unmanageable. And in doing so, they’ve accomplished a challenging task: simultaneously saving money and adding value.

While navigator programs may have initially been conceived to assist individuals with poor health literacy, providers and payers have come to realize that even health professionals are bewildered when they get sick. One recent study from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare and Research Quality found that a mere 12% of adults have the necessary knowledge to navigate the U.S. healthcare system. That particular finding was met with disbelief: Many observers doubted that the percentage was as high as claimed.

“As a physician in family medicine, I see myself as kind of a patient navigator,” says Dr. Todd Thames, senior regional medical director for Grand Rounds. “But I don’t have insights into the patient’s benefits ecosystem; it may be rich and valuable, but I don’t have access to that and I can’t leverage billing issues. And instead of finding care that solves their problems, people are met with obstructions and obstacles.”

Companies such as Grand Rounds simplify complexity, Thames adds. “It’s all about helping the member through this journey. Making it more efficient means clinical outcomes are better for patients and healthcare.”

While the industry has long been aware of glaring disparities based on race, income, education and gender, the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement made it impossible to look away.

“COVID-19 and the continued racial inequality experienced in 2020 forced employers and health plans to reassess their benefits offering and evaluate it through a DE&I and health equity lens,” explains Colin Quinn, cofounder and CEO of Included Health, a platform focused on improving care for LGBTQ+ employees, in response to emailed questions. “As a result, we’ve seen benefits leaders investing heavily in tailored solutions that cater to the unique health needs of underserved member populations, rather than accepting the previous one-size-fits-all approach.”

Lillie Shockney, RN, a patient navigator for the National Breast Cancer Foundation, believes awareness of these worsening disparities is especially profound in cancer care. As COVID-19 has chipped away at savings accounts and insurance coverage alike, financial barriers have increased for many patients.

“There are more unemployed people with less health insurance and less ability to manage co-pays,” she notes. “And that’s happening at a time when cancer drugs are more expensive.”

Thus, patient navigation becomes increasingly crucial for populations that too often feel disregarded. “For the LGBTQ+ community, healthcare is so much more than a trip to the doctor,” Quinn says. “It’s a receptionist using your correct pronouns, an OB-GYN not assuming you’re pregnant, a primary care physician who celebrates your choice to go on PrEP [pre-exposure prophylaxis] or parents researching to find a supportive pediatrician who will encourage your kid to be who they are.”

Quinn adds that 40% of Included Health’s LGBTQ+ members have had a negative healthcare experience, while 35% actively postpone or avoid care today. That percentage is three times greater than the overall U.S. population.

“Finding culturally competent, affirming providers isn’t impossible, but it is exhausting,” he continues. “Nearly a tenth of Americans identify as LGBTQ+, but lists of queer-friendly providers are out-of-date or unvetted or woefully overestimate a provider’s experience in working with our community.”

And that’s before the glut of digital health tools are entered into the equation. Despite the promise of seamless, connected care — a hook baited by everything from fitness devices to portable electronic health records — health tech was, until the pandemic, largely recognized as a disappointment by patients and providers. But COVID-19 and last year’s CARES Act changed that perception almost overnight, opening doors for virtual care and, in the process, vastly enhancing opportunities for patient navigators.

“We’ve had about 10 years of innovation around virtual care and virtual modality in nine months,” Thames says. “We are coming to understand there are some very effective engagement and treatment modalities that we can leverage in a virtual world. If I can reach my patient where they are, by phone or computer, I can bring them a whole different level of patient-centricity.”

To that point, Grand Rounds announced a merger with Doctor on Demand, a virtual platform, in March. Thames believes the newly united company is poised to tackle the $300 billion problem of uncoordinated care in the U.S.

“It’s revolutionary,” he proclaims. “With visibility across the care journey and different platforms, we can provide a more comprehensive experience — and that leads to better outcomes for patients.”

But don’t forget the bottom line: There’s more and more evidence that patient navigation saves money, making it easier for employers and providers to pony up for new programs.

That neatly complements the broader, more established body of evidence that they increase efficiency. “Many studies have been shown how navigation can make a difference, reducing no-shows, hospital readmissions and non-adherence to treatment plans,” says Sharon Gentry, program director at the Academy of Oncology and Patient Navigators. Much of the saving stems from streamlining care and decreasing duplication of services.

But new research from Accolade, a health and benefits solutions firm, offers some stunningly specific data points. Conducted by Aon, it builds on Accolade’s own research from 2018 and 2019. Encompassing data from 16 million members, the new findings are based on a comparison of two large employers using Accolade’s personalized advocacy services. Comparing both one- and three-year results to a matched control group, the research revealed that use of patient navigation services saved employers an average of $782 per person and lowered total employer healthcare costs by 6.5%. Use of Accolade’s navigation services also curbed rising costs: The companies using Accolade saw healthcare costs grow just 2.7% from 2014 to 2016, compared to 7.8% for the control group.

The findings didn’t surprise Accolade, says Carolyn Young, the company’s chief actuary and EVP of engagement. “What was most impressive is that this research substantiates those savings in so many areas, including mental health, musculoskeletal, diabetes, asthma and cardiac conditions,” she notes.

Young believes these proof points make it easier for employers to get on board with navigation services. “HR departments have only a finite amount of money,” she says, acknowledging that programs such as Accolade aren’t cheap. “That’s why demonstrating that employers get their return back in the first year, as we have done, is so important.”

But while justifying the costs of navigation services is essential, it’s more essential that employers recognize just how much help people need managing their care. Per Accolade’s research, 76% of people feel uncomfortable with their ability to navigate the healthcare system.

“When someone gets a diagnosis or their child gets a diagnosis, it’s difficult to know where to start,” Young says. “Having someone who’s in your corner, someone who is an expert in your benefits, is important.”

That’s why navigation boosters stress the most important benefit of these services is that they inject the human element into an increasingly dehumanized process. As patients trudge from one specialist and procedure to the next, often over a period of many months, navigators can become the most familiar face in their treatment journey.

“This is a very intimate relationship, and we get to know each other well,” Shockney says. “When I am at a tumor board meeting, I am the patient’s voice.”

Like many navigators, Shockney was once a patient herself: She was diagnosed with breast cancer first in her 30s and again in her 40s. That serves to bond navigators with their work in a way that few other professionals experience.

“For many of us, it’s as much a calling as it is a profession. And that makes it easier for patients to listen to us,” she adds.

At a moment when patients may be drowning in information — some good, some bad — navigators are trained to ask important questions. “‘How much do you know about your cancer? And how much do you want to know?’” Shockney says. “We ask what they’re hoping for and what they’re most worried about. We ask about what brings them joy.”

That intimacy has impact. Shockney recalls working with a breast cancer patient who worked as a bank teller by day but dreamed of becoming a concert pianist. “One of the side effects of a drug commonly used for her type of cancer is peripheral neuropathy — numbness, tingling and pain in the fingers, which can be permanent.”

The patient had never confided in her doctor about her musical ambitions, and the doctor had never told the patient about that particular side effect. “But because I knew both, I was able to make sure she got treated with a different drug,” Shockney says.

Stories like that travel far and wide, increasingly making patients aware of the importance of quality navigators. Gentry expects that trend to intensify as patient empowerment continues to surge. Just as patients ask about the best surgeons and specialists, she notes that, “We already see lots of interest on social media, with people asking, ‘Who was your navigator?’”

Which isn’t to say the trend isn’t without its drawbacks. Navigators, patients, providers and pretty much everyone else involved with the process acknowledge that the growing need for these services represents an admission that modern healthcare is disjointed and dysfunctional. “For many people, navigating the healthcare system is a bit like being in a foreign country and not speaking the language,” Thames says.

Health decisions, after all, often get made because they are suitable for payers or providers, rather than patients. That’s why navigation is so important, Gentry says: It puts patients in the middle of the room. “How do we get them through the system, despite barriers and challenges? How can we lead them to the best outcome?”

And navigation works. “Anytime you’ve got navigators involved, whether they are patient navigators without a clinical license or clinical licensed navigators, such as nurses or social workers, they will improve that patient experience and improve patient satisfaction,” Gentry adds. “They will also improve patient outcomes: getting diagnosed earlier, getting into treatment earlier and completing treatment. They have fewer hospitalizations and emergency room visits and more value-based care.”

From the May 01, 2021 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media