About nine years ago, after the birth of their daughter, Tess, Bo Bigelow and his wife Kate McCrann moved from New York to Maine. Bo, a commercial litigator, planned to find another legal job; Kate, a gastroenterologist, was set to practice locally.

Before long, however, Tess’ developmental issues transformed Bigelow first into a stay-at-home caregiver and then an advocate. Frustrated by the inability of myriad doctors to identify Tess’ condition – even a whole-exome sequencing test failed to result in a conclusive diagnosis – Bigelow went public with his story and frustration via a heartfelt blog post that he amplified via social media. Fewer than 24 hours later, a Baylor University researcher reached out. Within weeks, Tess became the eighth person diagnosed with a rare mutation of the USP7 gene.

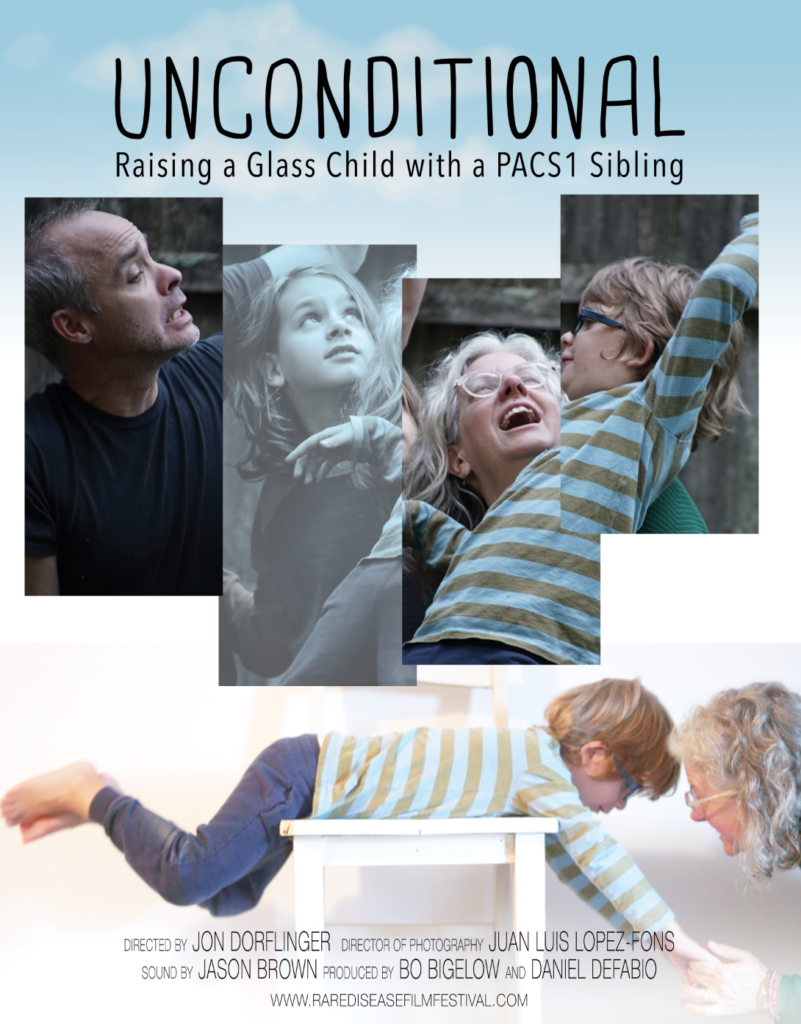

Since then, Bigelow and McCrann cofounded the Foundation for USP7 Related Diseases, which seeks to identify additional patients and fund research towards a cure. Along the way, Bigelow met Daniel DeFabio, “another rare disease dad,” who had made a film about his son’s battle with Menkes Disease. The two stayed in touch and, in 2017, DeFabio proposed organizing an event devoted to the screening of films about rare diseases and discussions about a range of conditions.

“We were just getting our foundation off the ground, so I told him, ‘I’d love to work with you on something, but this is not it,’” Bigelow recalls. “But he said that there was no better way to find other patients than by making a film, and that I should do one.”

When Bigelow suggested that the entirety of his filmmaking experience was “making funny videos” on his phone, DeFabio volunteered to help with editing and production. Bigelow’s Tess Is Not Alone: A USP7 Story was completed in 2017.

Bigelow and DeFabio had modest ambitions for the first event, which they dubbed Disorder: The Rare Disease Film Festival. “The goal was to show our two films and maybe another few, and maybe get a sponsor to cover costs,” Bigelow says. “We didn’t know if anybody would come. It’s not like a Jim Carrey film festival, where you’re going to be laughing and having a good time. It’s not a fun night. It’s about chronic pain and families dealing with really tough stuff.”

The idea immediately blew up in Boston, where the first festival was held, and beyond. What encouraged Bigelow and DeFabio most was how, in their minds, the announcement of the festival alone catalyzed a degree of action they hadn’t previously seen.

“Call it a cynical attitude, but Daniel and I had to that point seen a lot of efforts in rare disease about awareness, but they didn’t go anywhere,” he explains. “You ‘like’ my thing on Facebook, it doesn’t do anything. The goal was awareness plus action, so you needed to get all the right people in the room and have those conversations. There can never be enough of, ‘I did this thing with this disease, maybe it could work with that one.’”

Held in Boston on October 2 and 3, 2017, the first Rare Disease Film Festival featured 30 films and was backed by rare-disease advocacy organizations (NORD, Global Genes, Beyond the Diagnosis) and pharma (Premier Research, Alnylam, Sanofi Genzyme, Shire, Vertex) alike. Despite its success, Bigelow and DeFabio felt that a change in venue for this year’s festival – to San Francisco on November 9 and 10 – was a necessary step.

“We thought it was a good idea to start over. We want to see who we can meet and what new collaborations there can be,” Bigelow says.

Partners added for this year’s festival include Takeda, BioMarin, CSL Behring and BridgeBio Pharma. The screening slate hasn’t yet been finalized, but At the Edge of Hope, about life with Batten Disease and other conditions, and animated short Ian, about how a wheelchair-bound child navigates schoolyard play, have already been accepted into the festival.

In the wake of his experience with the festival, Bigelow has come to believe that film is underutilized by health and pharma organizations as a channel. “It has unique power in our culture right now,” he says. “When you’re seeing something in a theater, you can’t fast-forward and you can’t multitask. You’re kind of forced to slow down a little.”

Only when pressed does Bigelow acknowledge the extent to which his work has impacted patients, not just ones diagnosed with a USP7 mutation, but those with other ultra-rare disorders. In the two years since Life & Atrophy, a film detailing one family’s quest to treat a child afflicted with spinal muscular atrophy, screened at the inaugural festival, Biogen’s Spinraza has transformed treatment of the condition. The Genetics of Hope, a sequel of sorts detailing the role the SMA community played in the development of Spinraza, is set to screen in San Francisco.

“After sitting in the audience and watching [Life & Atrophy] in 2017, then to see how much has changed in less than two years – that’s exactly what we hoped for,” Bigelow says. “It’s not happening with all diseases, but it still blows me away.”

As for his efforts to locate more patients with USP7 mutations, Bigelow says that, as of late August, the number is up from eight at the time of Tess’ diagnosis to 52. “We know other patients are out there,” he says. “It’s about the whole-exome sequencing coming down in price. We’re hoping it gets to the point where you can walk into Walgreens or CVS and get your genome mapped for $20.”

The Third M is MM&M’s weekly health media column. Got ideas or questions? Contact Larry Dobrow at [email protected]