The Biden administration announced this week it will begin providing COVID-19 booster shots to Americans starting in September. Skepticism over the scientific merits of the decision notwithstanding, the announcement prompted questions as to whether the U.S. is doing enough to deliver on its stated “vaccine diplomacy” goals and address disparities in vaccine equity around the world.

That tension was first highlighted earlier this month, when the World Health Organization called for wealthier nations to refrain from distributing booster shots until the vast disparity in global vaccine equity was addressed. The agency asked for a moratorium on booster shots until 10% of the population of every country in the world could be fully vaccinated.

“I understand the concern of all governments to protect their people from the Delta variant, but we cannot and should not accept countries that have already used most of the global supply of vaccines using even more of it while the world’s most vulnerable people remain unprotected,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said at a news conference.

Since the start of vaccine distribution in December 2020, about 58% of the population in high-income countries have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, according to Our World in Data. That’s in comparison to a mere 1.3% of the population of low-income countries. Specifically, wealthier countries like the U.S., the U.K. and Canada have fully vaccinated at least half or more of their populations, compared with 3% or less of the populations of low-income nations such as Vietnam, Egypt and Nigeria.

In short, the world has barely moved the needle in addressing the global vaccine disparity since the issue was first highlighted months ago. As a result, public health experts are concerned that meeting the WHO’s goal of vaccinating 10% of the population in each country by September – enough to cover at least frontline workers in those countries – is unlikely.

“The picture of global vaccine equity continues to be one that’s highly troubling,” said Josh Michaud, associate director of global health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “If low-income countries as a whole are at 1% right now and they have the same projection in their rate of vaccinations, if nothing changes we’re looking at 3% of the population of those countries being vaccinated. It will continue to be a problem – in fact, the gap between the haves and have-nots will increase over time.”

Jason Hall, managing director at healthcare consultancy Avalere, agreed. “Reaching the goal by the end of September, based on where we are now, will continue to be a challenge. Until we have additional vaccine options available, and the established manufacturing capacity in the global footprint that manufacturers are trying to establish now, we will continue to be slower in our response than we wish.”

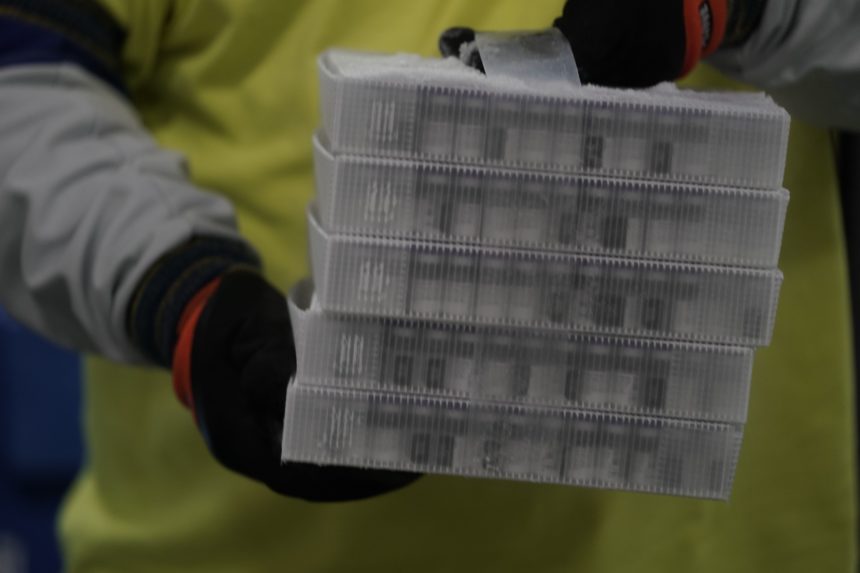

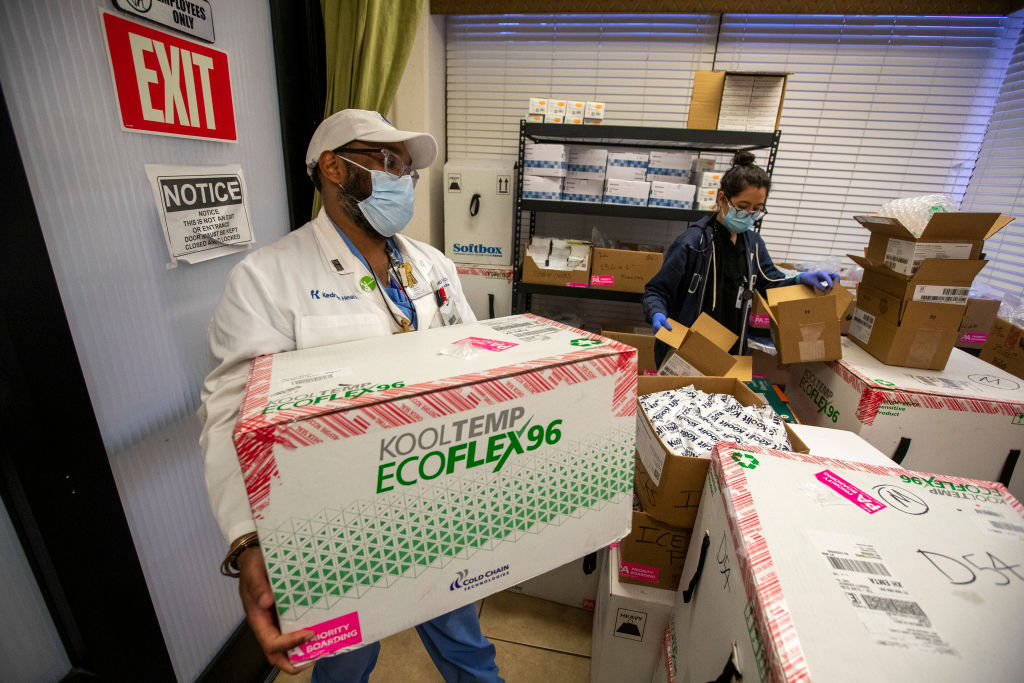

As part of efforts toward vaccine equity, President Biden has pledged to donate 500 million doses of vaccines to countries in need. The first of those doses are being shipped to Rwanda through COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX). The administration has said it plans to deliver 200 million of its 500 million dose pledge to countries by the end of this year, with the other 300 million to be distributed in the first half of 2022.

But skeptics argue that the current efforts aren’t enough. Upon learning about the imminent booster shots, nonprofit Oxfam America characterized the country’s actions as “vaccine hoarding.”

“The recommendation for a third dose of vaccines for Americans, even as front-line medical workers in much of the world wait for their first shot, underscores the need to urgently and massively increased production so that everyone, everywhere could have access to these life-saving vaccines,” said Ofxam senior manager of private sector advocacy Robbie Silverman in a statement.

“This vaccine hoarding is not only morally wrong, but also shortsighted and dangerous,” he continued. “As the Delta variant clearly demonstrates, if COVID is left unchecked in other parts of the world, a mutation can threaten the effectiveness of our vaccines.”

Michaud, however, noted that even if the U.S. were to donate 100 million doses that it plans to use for booster shots, that sum would barely make a dent.

“100 million doses is a lot, but in the grand scheme of things, in terms of the needs around the world, it’s pretty small,” he explained. “The booster question is a highly visible and understandable target for people talking about vaccine equity, but moving every booster dose over to COVAX is not going to be the thing that solves this problem entirely.”

Indeed, the entire pledge of 500 million donated shots is dwarfed by massive need around the world. That’s why many experts believe the focus should be on other solutions, such as increasing manufacturing capacity.

Hall pointed to a related challenge: making sure that vaccine distributors can cover the proverbial “last mile.” “Getting vaccines into a country or a region is not easy, but it’s at least somewhat established and able to leverage existing capabilities. Getting doses into local communities and more rural areas is where the challenge lies.”

Then there’s ongoing vaccine hesitancy – which has been playing out uniquely in different parts of the world – as well as related needs for increased education and awareness around vaccine safety and efficacy.

More vaccine options would obviously help. “There needs to be further development and improvement upon existing vaccines to make sure their supply, distribution, storage and handling requirements are more flexible for global distribution requirements,” Hall said. “That way, it’s as easy as possible to move products throughout the supply chain and get them to individuals as quickly as possible.”

Michaud suggested another short-term solution: finding a way to harness the excess vaccine supply many states currently have.

“Shifting some of that supply is one option and not a lot of countries have decided to do that,” he explained. “As vaccination has slowed down here, there’s probably a lot of vaccines sitting out there not being used. Trying to iron out some of these inefficiencies could be helpful.”

Longer-term, the biggest need is increasing manufacturing capacity worldwide. Alas, that’s a challenge that even the biggest optimists don’t believe will be addressed anytime soon.

“There’s only so much capacity out there in the moment,” Hall said. “Manufacturers are finding the available capacity they can to increase manufacturing. But at some point in time, we’ll need a bit of a larger shift in focus to establish more capacity in order to meet the global demand that we have for vaccines.”