Virtually overnight, Incivek and Victrelis changed the standard of care for treating hepatitis C virus. But they’re not in the lead position for a second generation of treatments, says Noah Pines, who reviews the all-out sprint to eradicate HCV, plus what’s emerging from antiretroviral, antibiotic and vaccine pipelines

Move over, Incivek and Victrelis. Standard of care is about to change again for the 170 million people around the world who have chronic hepatitis C virus. Future combinations will be comprised only of oral medications. These are convenient and well-tolerated, just like today’s HIV/AIDS antiretroviral regimens.

US sales of the virus-suppressing drugs—combined with anti-infectives, vaccines and other products like interferon—totaled roughly $24 billion in 2011, a 9% increase over the prior year, according to Source Healthcare Analytics. Over the next two to four years, revenues could get a big boost from new treatments.

Vertex’s protease inhibitor Incivek, which hit the market in May 2011, nearly doubled the hepatitis C virus (HCV) cure rate to 79% and cut treatment time in half for most people naïve to therapy. It won a battle for market share against Merck’s Victrelis, racking up $1 billion in global sales in under a year. Prescription growth for both has leveled as attention has turned toward another wave of curative combination regimens. “HCV is the bomb for drug developers these days—the outlook for patients is improving a lot,” says inThought director of research Dr. Ben Weintraub.

Several analysts now believe the best treatment “backbone” option in HCV is probably an NS5A replication complex inhibitor plus a nucleotide analogue inhibitor (or “nuc”) without ribavirin. The hottest right now is Gilead’s GS-7977 and daclatasvir, an NS5A from Bristol-Myers Squibb. The pair cured 80-100% of patients in clinical trials and was generally well tolerated.

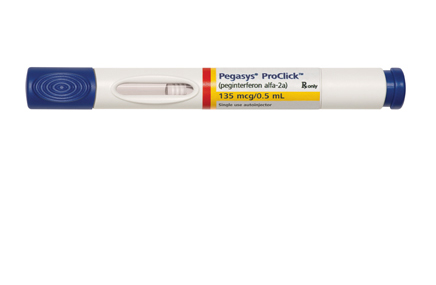

In addition to higher cure rates, these regimens add the convenience of all-oral dosing, unlike Victrelis and Incivek, each of which needs to be mated to interferon (INF) and ribavirin, and their cumbersome side effects that have kept many off treatment.

“We are quickly moving to an exciting treatment paradigm for HCV, one that spares the use of interferon,” says Dr. Raymond Chung, a hepatologist at Harvard Medical School. GS-7977 could be approved as early as 2014, while daclatasvir is expected in 2015.

INF-free regimens could expand HCV to a $10-billion market by 2017, estimates Sanford Bernstein analyst Dr. Tim Anderson. The industry arms race—Gilead spent a cool $11 billion to acquire ‘7977 developer Pharmasset, after which BMS dropped $2.5 billion for HCV drug firm Inhibitex—underscores the potential size, he says.

To reach their potential, therapies must reach the non-treated segment. “The success of any new agent launch in the category will depend on gaining insight into reasons for delaying therapy, and…‘unlocking’ this patient population,” says Scott Cotherman, chairman of TBWA/WorldHealth and president/CEO of CAHG, the agency of record for GS-7977.

There could be room for several players. “One-size-fits-all, while ideal, will likely be a challenge,” says Paul Daruwala, who headed up the Incivek brand team before starting a consulting firm. Just where the room is (geographically and patient type) “is what most are trying to sort out, no matter what one has in their portfolio.”

In addition to its NS5A, BMS is developing asunaprevir, an NS3 protease inhibitor, and pairing it in an all-oral combo with daclatasvir. Analysts are excited about numerous other pipeline assets from Abbott Labs, Johnson & Johnson, Vertex, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Merck, Achillion and Idenix.

Another big question is how long the sales window would last. Says Anderson, “HCV is not like other disease categories, where you have a chronic disease base that exists in perpetuity. You are eradicating disease over a short course of therapy, so you are going to exhaust the treatable patients.”

For now, drugmaker focus is on testing. The CDC recently recommended that people born between 1945-1965 (i.e., Baby Boomers) get screened. This was “an important step toward addressing the growing epidemic of chronic hepatitis C,” says a spokesperson from Vertex, which teamed with the American Gastroenterological Association on a screening and educational campaign called I.D. Hep C. If such initiatives have teeth, they could ensure an influx of new patients once those receiving current therapies are cured.

In HIV, clinicians have been frustrated with the inability to prevent infections. In July the FDA approved Gilead’s Truvada for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in those who are confirmed HIV negative. “The effectiveness is about 95% in those who take the medication—a rate so dramatic that we must take these data sets into account,” says Harvard researcher and instructor Dr. Calvin Cohen.

The next generation of HIV drugs is moving toward all-in-one combination pills, like Gilead’s “Quad” pill (awaiting FDA approval) which joins a new integrase inhibitor and pharmacologic enhancer with Truvada. The field “is now focusing on how you create regimens that are safe enough to live on long-term and simple enough to reduce adherence errors,” adds Cohen.

GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Shionogi are highlighting a trial showing that experimental integrase inhibitor dolutegravir, paired with Viiv’s Epzicom, showed superiority vs. Gilead’s one-tablet Atripla (88% vs. 81%, or a numerical difference of 7%). In an earlier trial pitting Quad against Atripla, the difference was about 4%.

An Epzicom-based pairing would have trouble against Quad, says ISI Group biotech and pharmaceuticals analyst Dr. Mark Schoenebaum in a research note. “Recall that Epzicom has baggage: potential safety concerns (CV) and probably inferior virologic control to Truvada. And docs know this.”

Another thing infectious-disease specialists are hungry for is new antibiotics. Companies have been tackling the C. difficile bacterium from different angles (see sidebar). But, “The big thing in anti-infectives is the lack of development of any new gram-negative drugs,” laments Dr. Alex McMeeking, associate professor, NYU School of Medicine. “While we hear about far-off possibilities, our patients age getting ‘eaten alive’ by highly resistant gram-negative organisms.”

Meanwhile, says Dr. Ian Frank, professor at the University of Pennsylvania, the IDSA’s 10×20 initiative to develop 10 new antibiotics by 2020 “is a statement as to the lack of options in the world of antibiotics right now.”

Infectious disease dynamics

ANTIBIOTICS With just two new approvals since 2010 (Optimer’s Dificid for CDif. in 2011, Forest’s Teflaro for skin infections/pneumonia the year before), clinicians face a dearth of new antibiotics, especially those that treat gram-negative bacterial infections. “Our patients are getting ‘eaten alive’ by highly resistant gram-negative organisms,” says one specialist. IDSA’s 10×20 initiative to develop 10 new antibiotics by 2020 “speaks to the lack of options,” says another.

GENERICS While generic versions of antiretrovirals are just starting to make their impact felt in the US, they have already enjoyed a substantial impact in non-Western markets. Look for a crop of generics to take a considerably bigger bite in developed regions soon, as such brands as Abbott’s Kaletra (2013), J&J’s Prezista (2014) and Gilead/BMS’ Atripla (2018) roll off the patent cliff over the next few years.

HEP. C As anticipation builds for new entrants, sales and prescriptions for Vertex’s Incivek and Merck’s Victrelis, both of which launched in 2011, are leveling. The first of a new wave of all-oral drugs that do a better job curing the hepatitis C virus (HCV) could arrive as early as 2014. There could be several of these, and they could expand HCV to a $10 billion category by 2017, says one analyst.

HIV/AIDS One-tab wonders continue to proliferate, namely Gilead’s Complera, approved last August, and the company’s next big hope—the “Quad” pill, under FDA review. But Gilead could see its gold-standard Atripla ($2.8B in 2011 US sales) threatened by another combo pill combining GSK’s experimental integrase inhibitor dolutegravir with Epzicom that has shown superiority vs. Atripla (88% vs. 81%). Co-developers Pfizer and Shionogi also stand to gain.

TESTING & PREVENTION While there is no HIV/AIDS vaccination in sight, the FDA in July approved Gilead’s drug Truvada for prevention in those confirmed HIV negative, a hotly debated move. In HCV, Vertex, Merck and Roche continue to push for screening. “Only about 10% of [HCV] patients get diagnosed and treated in the US,” says inThought’s Dr. Ben Weintraub. “We expect better diagnosis and screening in our models, so if that does not happen it will be a disappointment.”

VACCINES Pfizer won fast-track approval to market its Prevnar 13 vaccine in adults over 50 in December, which could boost sales despite lack of CDC endorsement, while the FDA okayed Novartis’ Menveo shot for meningococcal disease this year after a delay. In the pipeline, analysts are eying Sanofi’s Dengue vaccine, although, “I struggle to see how an emerging markets vaccine becomes a commercial killer,” says Sanford Bernstein analyst Dr. Tim Anderson.

From the August 01, 2012 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media