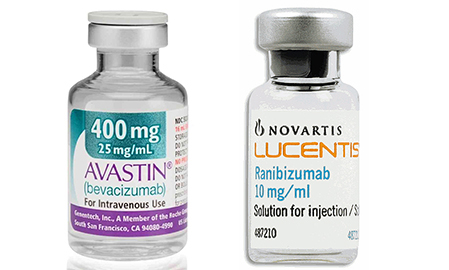

A study published in Health Affairs by researchers from the University of Michigan’s Health Management and Policy and Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences departments say research shows that Avastin and Lucentis are comparable for treating age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema, and that switching patients using Lucentis to Avastin would save the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid $18 billion over ten years—and could save patients an aggregate of almost $5 billion during this same period.

Avastin, which is not indicated for either of these conditions, is being used off-label to treat them. This has been a lonstanding concern for the drugmaker Roche and its subsidiary Genentech, which make both of the drugs. The companies have been criticized for trying to stymie off-label ophthalmologic use of the cancer-indicated Avastin through efforts such as unwieldy packaging that make breaking it down into eye-appropriate doses difficult, as well as simply not pursuing eye-related indications for the cancer medication.

What’s new is that the researchers are pushing for consideration of off-label use, and are proposing and incentive that would sweeten the deal for doctors doing so. Researchers note that doctors currently have little incentive to prescribe Avastin, because their reimbursement rate is based on the medication’s price. Therefore, prescribing the $2,023-per-dose Lucentis is financially more rewarding than prescribing $55-per-dose Avastin. Their suggestion: pay doctors the Lucentis incentive for Avastin prescriptions. By their calculations, if this reimbursement converted 8% of Lucentis prescriptions into Avastin prescriptions, CMS’s financial position would stay the same. Over 8% conversion would tip the system into savings mode.

Researchers also note that changing Lucentis prescriptions to Avastin prescriptions would ease patient financial pain, noting that retirees lacking supplemental insurance and dependent up on the average Social Security benefit end up spending at least 30% of their monthly stipend to cover Lucentis treatments “compared to less than 1 percent with use of [Avastin].”

They also acknowledge that this puts industry in a bit of a bind in that the switch would be good for payers and patients, but could pinch the pharmaceutical industry. And they are OK with this. Researchers acknowledge that encouraging doctors to switch treatment regimens “could blunt Genentech’s profit incentives to sell [Lucentis] or discourage the development of similar products.” Stunting or discouraging innovation is a common claim among industry defenders, but the researchers write it is worth the risk. They also note that Roche says the 18 clinical trials and $1.4 billion the company says it spent on researching and developing the drug is something to consider, but should not be enough of a reason to avoid a cost-savings approach of this magnitude. As a side note: recent data indicates the company has already recouped the $1.4 billion. Lucentis brought in $1.9 billion to company coffers in 2013 and Avastin wrangled almost $7 billion.

Although the above math seems like an easy give-and-take, one thing to consider is that the profits from a single medication are not siloed. Manufacturers have noted in pricing discussions that the money earned by the drugs that make it to market also have to cover the costs of the ones that have died in the pipeline. Two years ago Forbes’s Matthew Herper tried to account for the cost of drug development in an article that took into consideration the cost of failed ventures and found the median cost was around $4.2 billion for companies that launched more than three drugs and $5.3 billion for those which launched more than four. His calculations also included the note that 19 out of 20 drugs fail during development.

The researchers note that it’s still too-early to implement a switch and that more rigorous studies are needed. However, they indicate that the groundwork that indicates this prescription migration is a worthwhile research pursuit based on the information that is currently available. They note that government-funded comparisons between the drugs among neovascular age-related macular degeneration shows similar efficacy, but that safety needs to be better understood. The researchers note that Avastin may be associated with a higher risk of stroke and death, while also writing that cost-effectiveness studies show Avastin “confers a greater value” for both age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema.