When Sanofi was searching for a name for its once-daily diabetes injectable, already approved in Europe under the brand name Lyxumia, the drugmaker naturally tried submitting the same moniker to U.S. regulators. There was just one problem: That brand was deemed too similar to Zyprexa, a medication used to treat schizophrenia and manic episodes of bipolar disorder which is made by rival Eli Lilly.

Food and Drug Administration officials soundly rejected Sanofi’s first choice. Turns out, that scenario isn’t so uncommon. It’s for that reason that standard protocol calls for a primary name and an alternate to both be submitted to the agency. After the FDA rejected the initial name, Sanofi settled on a new one: Adlyxin.

But another issue cropped up. Unbeknownst to the company, regulators were already assessing an oncology product with “a very similar name,” recalled Brent McCain, Sanofi’s global head of marketing excellence for its diabetes and CV business unit.

Luckily for Sanofi, the oncology drug was eventually rejected, enabling Sanofi to swoop in and secure Adlyxin right before the drug’s launch.

Creativity via elimination

Naming a consumer product is fairly straightforward. You’ll want something memorable and meaningful that conveys what the product does or how it makes consumers feel. Trademark issues aside, the dictionary is your oyster, its contents ready to be mined, combined, edited, and altered to create

something magical.Naming a prescription drug is different. Sure, you’ll want something memorable and meaningful that conveys what the treatment does or how it makes patients feel. But in lieu of an open dictionary, you must select a name unique enough to appease a variety of regulators but not so unique that it reads like the alphabet threw up, in addition to checking dozens of other hard-to-fill, occasionally contradictory boxes.

All U.S. prescription drug names must be sanctioned by the FDA. Approval requires clearing a number of hurdles. Most importantly, the name cannot look or sound similar to existing drug names (in a variety handwriting styles and accents). There’s a good reason for this, of course: The FDA’s main priority is avoiding medication errors, which

kill an estimated 250,000 Americans each year.

To be viable, names cannot imply unsubstantiated claims, nor can they violate existing trademarks. Oh, and for drugs launching in other countries, a name should not mean or suggest anything offensive or unpleasant, for obvious reasons.

As more drugs are launched — last year, the FDA

approved 46 of them — the pool of available names dwindles. At the same time, the agency’s rules around alluding to efficacy claims have grown stricter over the years, and more companies are launching drugs internationally, which means new names must be approved by regulatory agencies in multiple countries.

Taken together, selecting a name has become “an increasingly complex process of elimination,” said Scott Piergrossi, executive creative director at the Brand Institute.

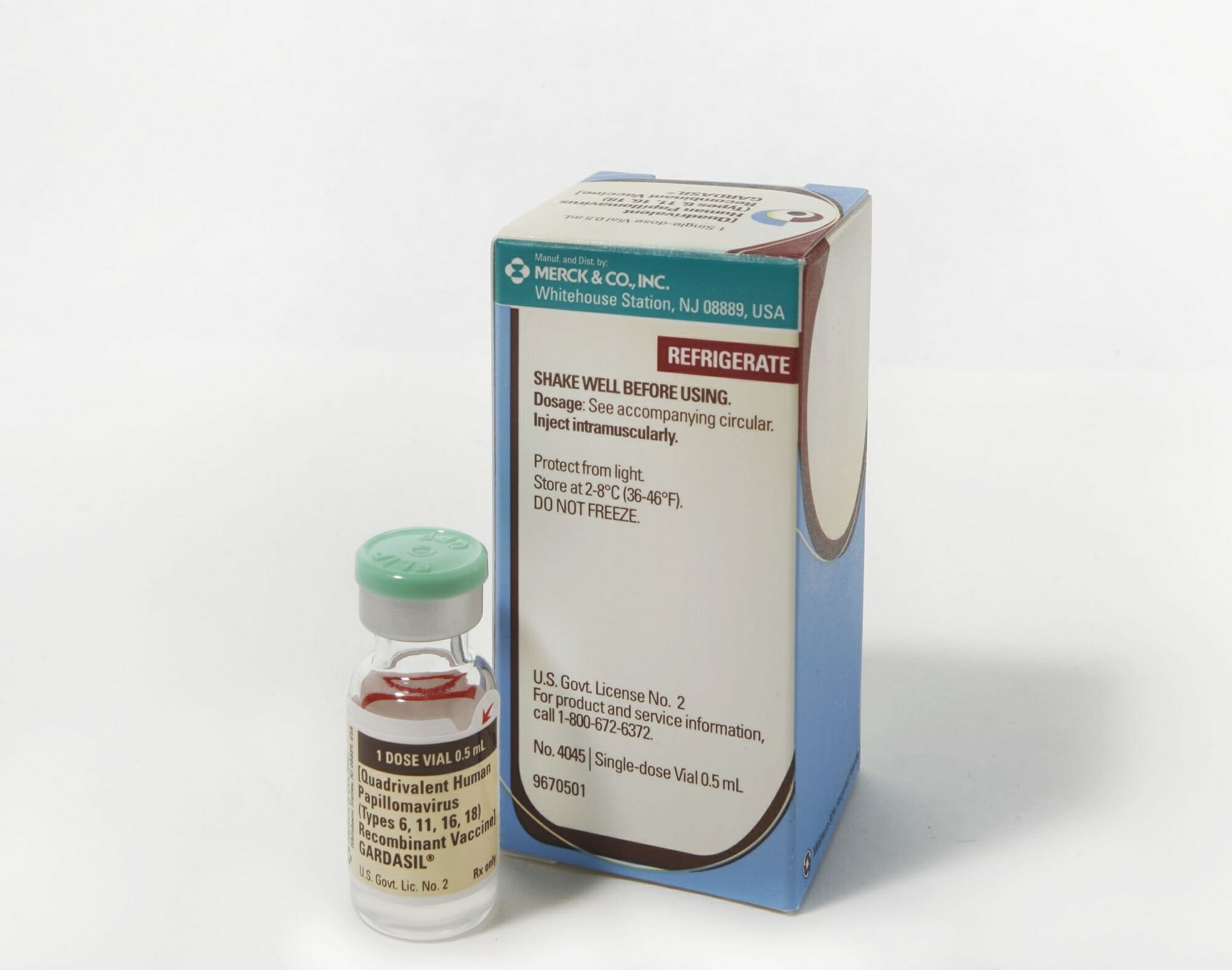

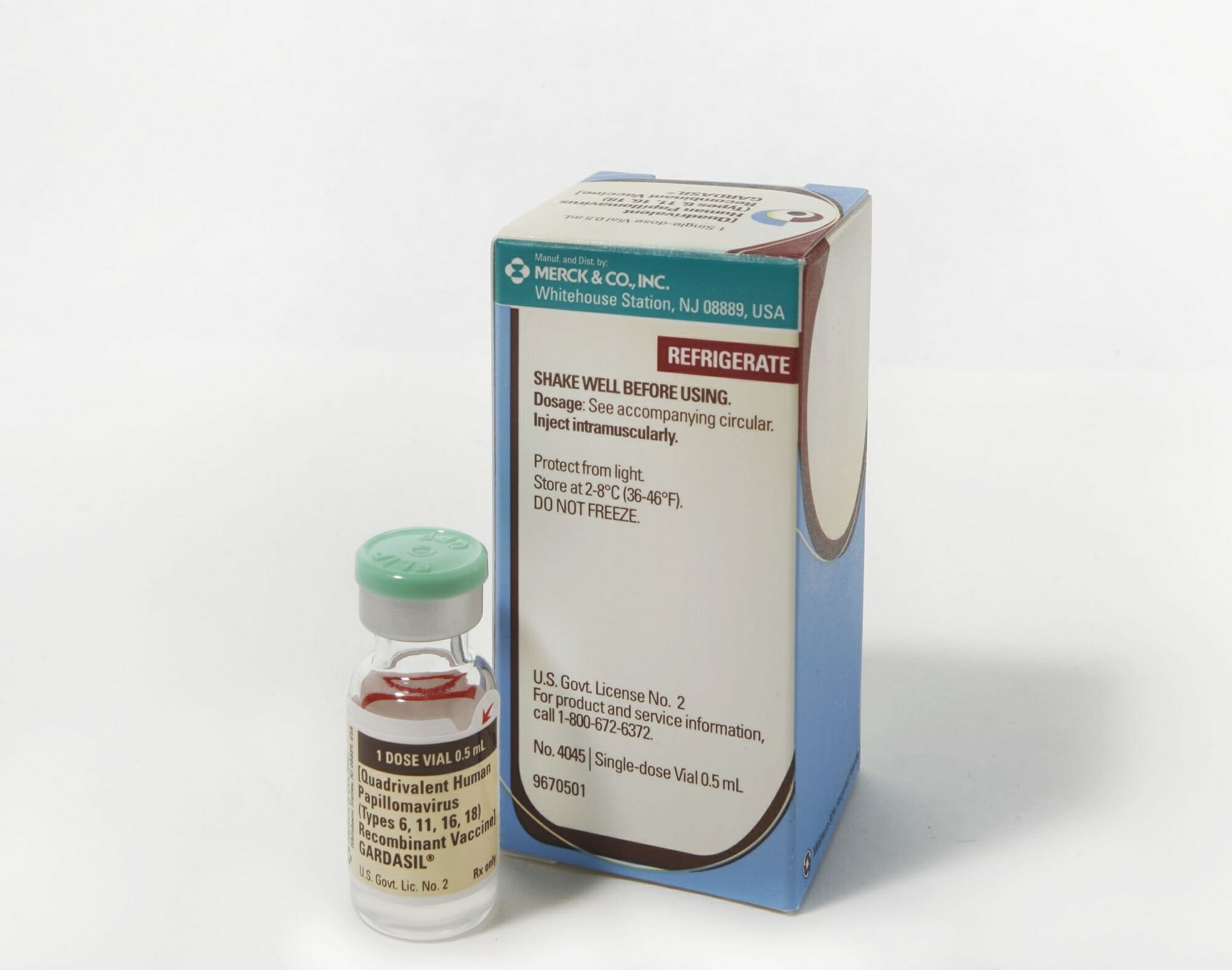

Over his 15-year tenure at the agency, Piergrossi has been involved in the development of more than 600 marketed brand drug names, including Gardasil, Merck’s recombinant human papillomavirus vaccine, and Latisse, Allergan’s treatment for lash growth. He’s watched as available options have morphed from the relatively familiar and easy-to-pronounce, to “novel” strings of letters that don’t typically appear in everyday language.

When meeting with new clients, “I like to tell them, ‘I know these names are very unique and some of them might not be what you expected,’” before assuring them that it’s all relative: in 10 years’ time, today’s options will appear simple and intuitive.

When it comes to this name-saturated future, “personally, I try not to think about it,” said Robert Recobs, president and CEO of OptiBrand Rx, another agency that develops drug names for pharmaceutical companies (previous hits include AbbVie’s autoimmune megablockbuster Humira, and Sunovion’s sleep aid Lunesta). Instead, he immerses himself in the individual challenge of finding a drug name that “relates to the practitioners and patients and avoids regulatory and safety pitfalls.”

While the field has grown more crowded and the rules tighter, the actual process of selecting a name has changed very little over the last decade, these experts said. Below, a step-by-step guide to how new drugs get named.

1. Hundreds of potential names are created by the agency.

The first step is simply creating a long list of possibilities. Recobs and his team usually sit down with pharma execs to talk about the drug in question and what they’re hoping the name will convey. Popular starting points include generating names that allude to a drug’s attributes, product composition, non-clinical end benefits, indication, or associated imagery.

That said, OptiBrand Rx regularly creates “blank canvas” names for clients, i.e. they sound nice, but don’t technically mean anything. Hundreds of names are created by the agency, which are screened for potential red flags — of which there are many.

OptiBrand Rx then runs candidates through proprietary software programs to eliminate those that are too similar to existing drug names. This includes testing how the name sounds when said in a variety of different accents, as well as evaluating how it appears in typed font and a range of handwritten samples. These steps are important: drugs that, at first glance, don’t look anything alike can run afoul of regulators.

Case in point: Sanofi’s Lyxumia example, where the FDA felt the name was too similar to Zyprexa. “There’s not a lot of alliteration there, but if you look at the letters above and below the line, when both are badly handwritten, you can see why there was concern,” Recobs explained.

Another example of this pitfall are the visual similarities between GlaxoSmithKline’s Avandia oral antidiabetic agent, and Coumadin, a prescription medicine used to treat blood clots. When spoken or typed the names appear distinct enough, but when handwritten in cursive, they become eerily similar. Mixing them up is “a mistake that could kill somebody,” Recobs said.

Names that might overstate a drug’s effectiveness or imply unsubstantiated claims are also flagged.“There are so many considerations. It’s hard to talk through them all,” said Dominick Cirigliano, OptiBrand Rx’s executive vice president of strategic research.

2. Around 100 names are presented to the client, who retains about 75 of them. The remaining names receive legal screens and are reviewed for trademark violations.

Piergrossi kicks off this stage with a pep talk. “It’s all about opening your mind to what a drug name could be,” he tells his clients. He discourages the popular exercise of having execs supply their favorite drug names to use as reference points, as the selections are typically simple, and intuitive in nature — characteristics that would make it nearly impossible for them to get past the FDA today.

“It’s always, ‘Oh, Flomax, or Lyrica, or Ambien.’ These benchmarks are really not necessarily applicable anymore because these are names that use conventional phonemic orthography,” he said.

What’s more, the FDA has become stricter about allowing embedded meanings that could communicate a claim. For example, drug companies love the name Victoza, the brand name for a Novo Nordisk diabetes injection, which was approved nearly a decade ago. “The idea of victory is probably a difficult one to get through now,” Cirigliano said.

Some leeway for conveying claims remains, provided the data supports the connection. Cirigliano worked on the name development of Acorda’s Ampyra, a prescription medicine indicated to help improve walking in adults with MS. At the time, the conventional wisdom was that “amplify,” like “victory,” was off-limits, but the name was approved, in part, Cirigliano said, because the drug actually does enhance neurotransmission which, in turn, amplifies MS patients’ ability to walk.

3. The list is further whittled down to around 15 to 20 names, which proceed into the marketing, name safety, and linguistic assessment phase.

At this stage, there should be a range of options still in the running, according to Piergrossi, including those that veer toward the “novel” side, as well as more conventional candidates. He advises that clients not get too hung up on a particular style just yet. Finding a name is both a science and an art; eliminating potential avenues before the market research stage can hurt the end result.

In addition to market research, the remaining names are run through safety exercises with prescribers to ensure there is no confusion that could lead to prescription errors. They’re also officially screened for linguistic issues, such as negative or inappropriate meaning or connotations in foreign languages. While informal linguistic pre-screenings take place far earlier in the process, at this point, the agency will reach out to in-country linguistic specialists for an up-to-date analysis. “There could be new idioms, slang terms, or collequisims that are not apparent to us,” Recobs said. “Language is always changing.”

4. The list is narrowed down to six to eight finalists, which are carefully reviewed by the client.

Compared with 10 or 15 years ago, this final group will likely include names that are longer and/or contain strings of letters that don’t often appear in everyday language. To get approved, a new name must “carve out a unique space for itself,” Piergrossi said. “That is very much the state of play today.”

Despite these limitations, unclaimed white spaces do exist. It’s still possible to find a name that maintains “some elements of basic, simple, and intuitive pronunciation,” said Piergrossi, such as AstraZeneca’s Fasenra, an add-on maintenance treatment for patients diagnosed with severe eosinophilic asthma, and Genentech’s Hemlibra, used to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes in adults and children with hemophilia A.

But Piergrossi is adamant that more novel names, when executed correctly, can be just as impactful. He points to Pfizer/Asetllas’ Xtandi, an androgen receptor inhibitor that treats men with a type of advanced prostate cancer, a name that is unique, memorable, and subtly meaningful: “There’s a slight inference of extending life as a prostate cancer drug, which is obviously an endpoint that it fulfills.”

5. The client selects one or two options, which are submitted to the FDA.

Again, Sanofi’s Adlyxin-for-Lyxumia experience is the cautionary tale here. A name always runs the risk of being rejected, so you’ll want a backup to avoid repeating the entire process, which typically takes anywhere from six to a year.

“There are so many products across so many different countries across so many different categories across so many different industries. It becomes difficult to find that intersection of what you want to say about your product and what is actually available out in the world,” Sanofi’s McCain added. “It’s not as simple as you would think.”

Clones, strings, and markers: playing the name game

As the pickings for drug names get slimmer, agencies are forced to adopt new name-generation strategies. Here are a few popular techniques, according to the Brand Institute’s Piergrossi.

Real-world clones. “You take a real word and tweak it a little bit so you keep the essence of that word. Most people, if exposed to the name enough, would get that link. And then you can create a campaign around the word, especially if it’s aspirational.”

Example: Harvoni, a treatment option for chronic Hep. C genotype 1, 4, 5 or 6 infection, which is a play on symphony and harmony.

Unique letter strings. “With these type of names, clients have to take a leap of faith. The prefixes are often distinctive, and not coined from any specific message.”

Examples: Hyqvia, an immune globulin indicated for the treatment of primary immunodeficiency, and Vraylar, which treats acute manic or mixed episodes of bipolar 1 disorder in adults.

Names that start with a letter marker. “A breakaway consonant is a strategy some clients love and some clients say, ‘We don’t want to see any of that.’ So it’s very much project team specific on what works and doesn’t.”

Examples: Qnasl, a corticosteroid used to treat nasal symptoms associated with seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis, and Kcentra, for the reversal of acquired coagulation factor deficiency induced by vitamin K antagonist therapy. “The K is the symbol for potassium, and centra derives from concentration, so potassium concentration.”

Double vowels: “When you write, double vowels aren’t very common. They can stand out.”

Example: Xiidra, used to treat dry eye disease. “Shire leveraged the two i’s to represent eyes. It’s a very creatively executed campaign.”

Longer names. “We’ve seen names get a little longer in the last 10 years. In 2010, 25% of approved names were two syllables. Last year, in 2017, it was 16%, and 11% the year before that. The more naming real estate you have, the more potential messaging you can embed, and the greater the name’s chance of standing out. If you have a nine- or 10-letter name, from a length standpoint you are eliminating a large percentage of potential conflicts because, relatively speaking, very few names are nine or 10 letters.”

Examples: Imbruvica, which is used to treat certain cancers, and Tecfidera, for relapsing forms of MS. “At nine letters and four syllables, these would be considered traditionally long. But they’re phenomenal names and very well-liked by the clients.”