On the 6th floor of Schneider Children’s Hospital in the Tel Aviv suburb of Petah Tikva, 30 children with Alagille syndrome and 2 with lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D) receive specialized treatment from a trio of pediatric hepatologists.

Across town, at Sheba Medical Center’s Edmond and Lily Safra Children’s Hospital, pediatric neurologist Gail Heimer, MD, PhD, supervises the 4th-largest dedicated Angelman syndrome clinic in the world. And down the street from Heimer, fellow pediatric neurologist Lidia Gabis, MD, runs the Keshet Center for Autism, one of the world’s top clinics for the treatment of fragile X syndrome.

It’s the same pattern in the capital city of Jerusalem, where physicians at Shaare Zedek Medical Center care for some 900 patients, both ultra-Orthodox Jews and Palestinian Arabs, at its sophisticated Gaucher disease unit.

Also in the capital, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center surgeon Haggi Mazeh has developed a new method to identify thyroid cancer with 94% accuracy — 55 years after Hadassah neuropathologist Moshe Wolman presented the world’s first case study of LAL-D in a baby born to closely related Iranian Jews. The infantile form of LAL-D eventually came to be known as Wolman disease.

When it comes to rare disorders, Israel — a New Jersey-sized nation of 9.3 million that’s made headlines this year for its highly successful coronavirus vaccination campaign — is clearly an emerging powerhouse.

Of the more than 387,000 clinical trials listed in the US National Institutes of Health database, 8372 involve sites in Israel, many of them focusing on diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), and cholangiocarcinoma.

The predominantly Jewish state is already home to Teva Pharmaceuticals, the world’s top generic drugmaker, as well as Kamada, which in 2010 won approval from the US Food and Drug Administration to market Glassia, the first liquid plasma-derived treatment for patients with emphysema due to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD). Kamada, headquartered at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, is now working on an inhaled augmentation therapy for AATD.

Experts say Israel’s prowess in diagnosing and treating rare diseases is a consequence of its unusual religious and ethnic makeup, as well as its focus on scientific research and its community-based healthcare distribution system — factors that led Pfizer to choose Israel as the first country to receive its vaccine against COVID-19.

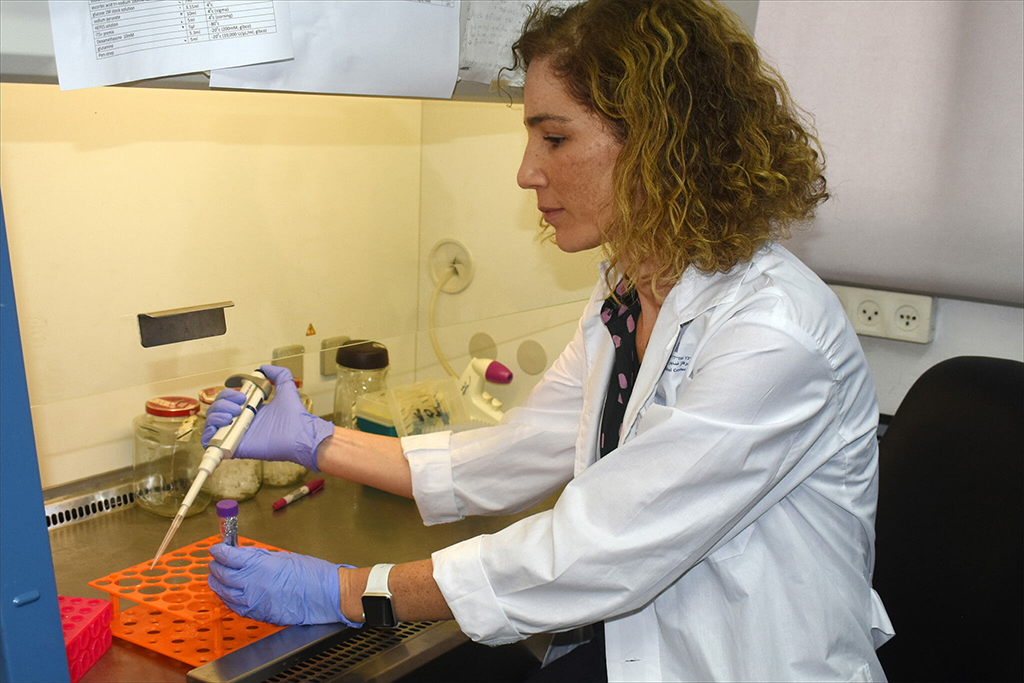

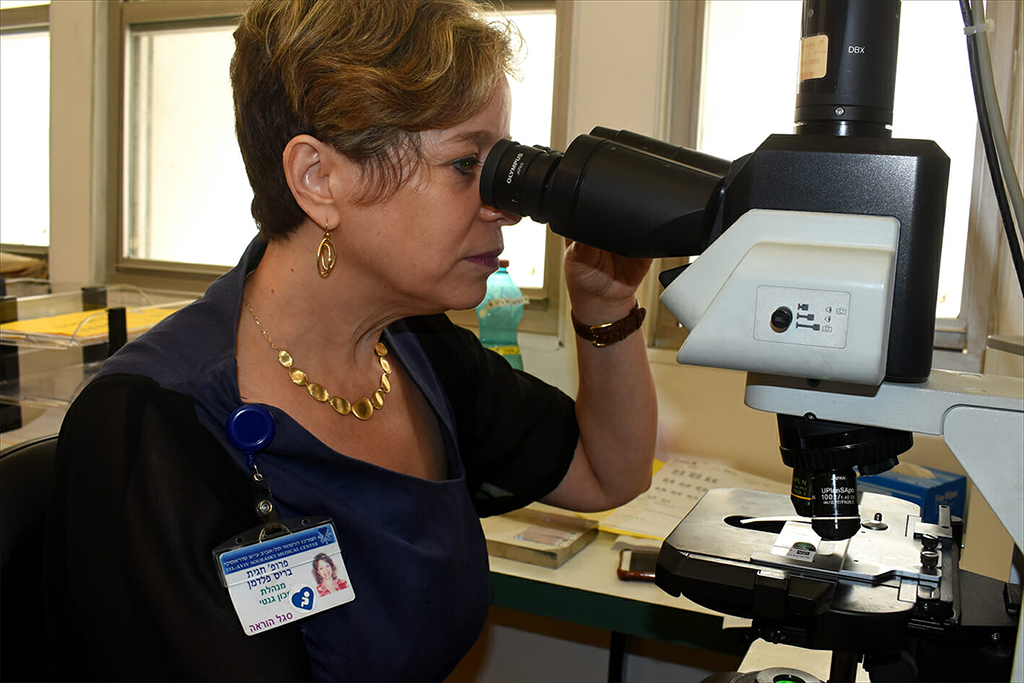

“We have such a mixture of ethnicities here,” said Hagit Baris-Feldman, MD, director of the Genetics Institute at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, also known as Ichilov. “Jews, Muslims, Christians, Druze, Bedouins, and Circassians each have their own unique genetic characteristics. And since some of these communities practice endogamy and consanguineous marriages, they have a high rate of mostly autosomal recessive disease. This means both parents carry the same mutation, leading to a 25% chance of having an affected child.”

For example, about 1 in 140 Israelis are believed to be carriers of fragile X syndrome, which is among the most common causes of intellectual disability; this compares to 1 in 250 Americans. In certain populations in Israel, the prevalence is even higher. In fact, 1 in 40 Sephardic Jewish women descended from Djerba, a small island off the coast of Tunisia, carry the fragile X mutation. The disease is also relatively common among Moroccan and Iraqi Jews and Ashkenazi Jews from the northern and central regions of Europe.

“When you talk about these small communities, the likelihood of finding the genetic culprit underlying their children’s problem is very high,” said Dr. Baris-Feldman, who also chairs the Israeli Medical Genetics Association and is an associate professor at Tel Aviv University’s Sackler Faculty of Medicine. “We can reach up to a 60% detection rate. This gives us an opportunity to study genes that nobody else in the world is aware of.”

Schneider’s Orit Waisbourd-Zinman, MD, said the 30 Alagille patients under her unit’s care represent most Israelis with that severe liver disease.

“Alagille is very interesting. With the same genetic mutation, you can have very severe or very mild symptoms — or no symptoms at all,” said Dr. Waisbourd-Zinman, who did her pediatric training and hepatology studies at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, where she worked with Alagille experts David Piccoli, MD, and Nancy Spinner, PhD.

“Sometimes, parents come in with a sick baby, and then we diagnose one of the parents with Alagille,” she added. “It’s not the same as being a carrier. In Alagille, if you have only one gene, you’re sick. But the spectrum of the disease is so huge, and it affects not only the liver but also the vascular system, the heart, and the kidneys.”

Adi Klein, MD, is head of the 1000-member Israeli Clinical Pediatric Association (known by its Hebrew acronym, HIPAK). The group’s upcoming winter meeting, organized by Paragon Group and scheduled for September 30-October 2, 2021, at Jerusalem’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel, will focus on rare conditions including Alagille syndrome, LAL-D, Gaucher disease, and other conditions that are far more common here than in Europe or North America.

“We will be emphasizing rare diseases we don’t really see in our everyday pediatric practice. But there are new treatments, and even though these conditions are rare, if you don’t have information to look for the symptoms, you can miss those patients,” said Dr. Klein, who runs the pediatrics department at Hillel Yaffe Medical Center in Hadera, north of Tel Aviv.

In September 2019, Israel — home to 130 SMA patients — became one of the first countries in the world after the United States to cover the $2.125 million cost of onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi (Zolgensma®), a one-time gene therapy developed by Novartis.

“When I started working here 20 years ago, we’d diagnose children with SMA but had nothing to prescribe them. I remember the discussions we’d have with families about their options, and whether or not they should be on ventilators,” Dr. Klein said. “Today, it’s a completely new era, where there’s a genetic exam to know if you carry that embryo. And if you get treatment early enough, it can change everything.”

This story originally appeared in Rare Disease Advisor.