The launch front in this category is relatively calm—for now. A movement is brewing to unseat the top diabetes drug, a long-acting insulin, as faster-acting products emerge. Joe Dysart on the intrigue in the metabolic pipeline, as drugmakers seek new ways to differentiate

Competitors in the diabetes space are jostling to bring products to market designed to either deliver insulin much more rapidly, or enable insulin to last much longer in the body once it’s there.

Diabetes plagues 25.8 million Americans—and seven million of them don’t know they have the disease, according to the National Institutes of Health. It’s the seventh leading cause of death in the US.

Meanwhile, during the first 11 months of 2013, sales of prescription diabetes products, along with those for obesity and hyperthyroidism, rose 9% vs. the prior-year period, to $23.8 billion.

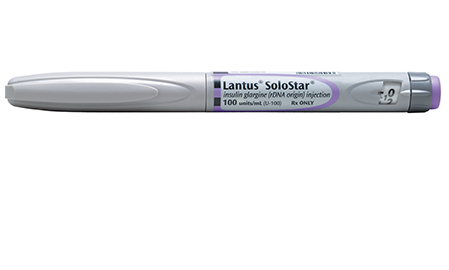

One of the most contested market sectors in the space is for drugs that enable insulin to last longer in the body. The sector is dominated by Sanofi’s Lantus, which brings in about $6 billion in global revenues.

To see a PDF of 2013’s Top 50 Metabolic Products, click here

While Lantus’s comfortable market position is in jeopardy—given that its patent is due to expire this year—its Paris-based manufacturer has been working hard to protect market share by developing an upgraded product, U300, which is getting close to market.

So far, researchers are encouraged that U300 has shown successful blood sugar control—similar to that of its predecessor—in a Phase-III study. Plus, U300 also clocked fewer instances of night-time low-sugar events than Lantus, a perk that promises to make it easier for diabetics to live with the disease. “To properly manage diabetes, it is critical to control blood sugar and to reduce the risk of low blood sugar events, especially at night,” says Matthew Riddle, a professor of medicine at Oregon Health and Science University, and principal investigator for the Sanofi-backed EDITION I study of this investigational new insulin. “I am encouraged by these findings.”

Sanofi has also beaten back major competition against U300 by lodging a patent infringement suit against Eli Lilly. The suit, brought earlier this year, essentially triggered a 30-month delay in Lilly’s journey-to-market for LY2963016, Lilly’s generic version of Lantus.

“For Sanofi, the delay not only provides Lantus with a longer period of marketing exclusivity—it also affords the company more time to switch to its purportedly new-and-improved version of Lantus,” says Tim Anderson, a global pharmaceuticals analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein & Company. “For Lilly,” he adds, “the delay merely means that it will have to sit on its hands a bit longer before launching its version of Sanofi’s drug.”

Brian Whalen, VP, science and medicine at medical ad agency Evoke Health, agrees. The move “has clearly positioned Sanofi well from a sales perspective, protecting prescriptions of Lantus from LY2963016, at least through the 30-month delay,” he says. Whalen expects Sanofi to leverage the time to strengthen relationships with its prescriber base in anticipation of U300’s launch, and educate prescribers about the benefits of U300 over Lantus.

Even so, Whalen still believes Lilly’s LY2963016 is the most important drug diabetics will see emerge in the next two or three years. “ LY2963016 will be among the first—if not the first—biosimilar medication marketed in the US for a condition as highly prevalent as Type 2 diabetes,” he says. “Assuming the Lilly product will have a purchase price considerably below that of Lantus, its commercial launch will allow for treatment in many more patients.”

Maybe so. But yet another major drugmaker—Merck—announced plans earlier this year to initiate Phase-III studies for a product very similar to Lantus, dubbed MK-1293. It’s partnering with Samsung Bioepis, a joint venture between Samsung Biologics and Biogen Idec, to manufacture and market the product.

“This agreement will help build our portfolio across the spectrum of the disease,” says Matt Strasburger, a VP at Merck.

Meanwhile, manufacturers specializing in delivering insulin as quickly as possible will watch for the FDA’s ruling on Afrezza from MannKind. That drug goes before the agency for approval this spring. An inhalable insulin, Afrezza is billed as faster-acting than traditional mechanisms, according to Hakan Edstrom, MannKind’s president.

This is the second go-round for MannKind on Afrezza, which was sent back to the drawing board in 2010 after attempting to switch inhalers on the product midstream during FDA trials. The new inhaler “is smaller than the previous inhaler that was studied and empties more efficiently—therefore requiring only a single inhalation in order to receive a full dose,” Edstrom says.

While MannKind is framing the drug/inhaler combination as easier to use, responsible for less weight gain and offering a lower risk of hypoglycemia, some have doubts. Those include key opinion leaders at a July 2013 roundtable organized by Leerink analysts. Experts at the meeting warned the new product could pose a safety risk.

The naysayers point to a similar, now-defunct product—Exubera, which had been marketed by Pfizer—which was associated with scattered cases of cancer in clinical trials. Pfizer abandoned the product in 2008. And Eli Lilly abandoned a similar product the same year.

But Edstrom disputes safety concerns. “In clinical trials of up to two years duration, observed changes in lung function were small, did not progress and resolved when treatment was discontinued,” he says.

“We have not observed a higher incidence of lung malignancies in Afrezza patients than the expected incidence in a similar patient population,” Edstrom adds. “In addition, the safety profile of Afrezza has been extensively examined in a non-clinical program including long-term carcinogenicity studies, which showed no increase in risk.”

Other diabetes drugs the industry should be watching include the SGLT-2 inhibitors, according to Whalen. “While barely a year has passed since the approval of the first-in-class SGLT-2 inhibitor, Janssen’s Invokana, the class is crowded with a second approval (AstraZeneca’s Farxiga), a third—empagliflozin—following shortly, and five additional inhibitors in various stages of clinical development,” he says. “Among these, however, Eli Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim’s empagliflozin may be the key product to watch.”

The reason? Empagliflozin will have advanced time in market ahead of options from Merck, Astellas and Taisho, and it may demonstrate benefits over the two already approved options, Whalen says.

The Lilly and Boehringer formulations also have a distinct advantage over Invokana, in that Invokana is dealing with a warning of renal impairment associated with its use, Whalen says.

Moreover, competitor Farxiga is expected to face tough-sledding against Lilly and Boehringer, given that it has been flagged by the FDA over bladder cancer concerns. Those worries have prompted the FDA to require a re-evaluation of existing data for Farxiga, Whalen says, as well as presentation of new data not previously available.

In contrast, there is no evidence that competitor empagliflozin shows any problems with bladder cancer. Plus, the drug also provides “reductions in HbA1C, as well as the weight loss and lowered blood pressure attributed to the SGLT-2 inhibitor class,” Whalen says.

Yet another experimental agent to watch is degludec, being developed by Novo Nordisk. Delayed by the FDA due to possible cardio risks, the drug promises to free up diabetics from daily dosing. “By shifting from a daily basal insulin + BID GLP-1 injection,” Whalen notes, “a combination BIW or TIW basal insulin + GLP-1 agonist—such as [Victoza], also manufactured by Novo—may be an attractive option for physicians whose patients may have adherence issues.”

CLINICAL CORNER

Results from clinical trials found that a commonly used drug might help Type 2 diabetes patients, while other trials clarified safety issues for two more drugs, quashing fears about increased heart-attack risks.

Salsalate, a drug used to treat arthritis has been shown in a study to lower blood glucose and improve glycemic control in Type 2 diabetes.

“It’s exciting,” says lead study author Allison Goldfine, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “Salsalate may have an important role in diabetes treatment and may help us learn more about how inflammation contributes to the development of Type 2 diabetes.”

Before winning FDA approval, the drug’s impact on heart disease must be evaluated. Goldfine is leading that study, expected to produce results in about two years.

On the Type 1 front, there’s also promise in the pipeline. Teplizumab, an investigational medicine that has been studied for nearly 20 years, replicated efficacy results in a recent Phase-II study, according to Jeffrey Bluestone, PhD, lead researcher and executive vice chancellor at the Diabetes Center, University of California, San Francisco.

The drug—also known as anti CD3—is designed to block the advance of Type 1 diabetes in its earliest stages, Bluestone says.

Among marketed products, a recent clinical trial concluded that GSK’s Avandia (rosiglitazone) showed no elevated risk of heart attack or death in patients being treated with the drug, when compared to standard-of-care diabetes drugs. The findings seemed to counter earlier trials, which reported in 2007 that the drug appeared to increase the risk of heart attack. The latest trial reflects “the most current scientific knowledge about the risks and benefits of this drug,” says Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Our level of concern is considerably reduced. Thus, we are requiring the removal of certain prescribing restrictions.”

Other safety-related research was reported for AstraZeneca’s Onglyza (saxagliptin). The Type 2 diabetes drug posed no increased risk for heart attack, stroke or cardiovascular death, according to a recent clinical trial evaluating 16,492 patients. “The results add important evidence to the overall body of data to further define the clinical profile of saxagliptin for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes,” says Deepak Bhatt, MD, MPH (pictured at left), a senior investigator with the TIMI study group, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and a principal investigator for the clinical trial. Adds Briggs Morrison, MD, executive vice president, global medicines development, AstraZeneca: “The data on pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in a study of more than 16,000 patients provide important and timely scientific information from a robust, randomized trial for the diabetes community.”

Other safety-related research was reported for AstraZeneca’s Onglyza (saxagliptin). The Type 2 diabetes drug posed no increased risk for heart attack, stroke or cardiovascular death, according to a recent clinical trial evaluating 16,492 patients. “The results add important evidence to the overall body of data to further define the clinical profile of saxagliptin for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes,” says Deepak Bhatt, MD, MPH (pictured at left), a senior investigator with the TIMI study group, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and a principal investigator for the clinical trial. Adds Briggs Morrison, MD, executive vice president, global medicines development, AstraZeneca: “The data on pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in a study of more than 16,000 patients provide important and timely scientific information from a robust, randomized trial for the diabetes community.”

But Onglyza is not completely out of the woods: at press time the FDA had announced a fresh inquiry to examine a possible link between the drug and heart failure.

From the March 01, 2014 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media