Endocrinologists have their guard up when it comes to biosimilar insulins and will keep patient use of the copycat biologics relatively low, even if they reach market, researchers predict.

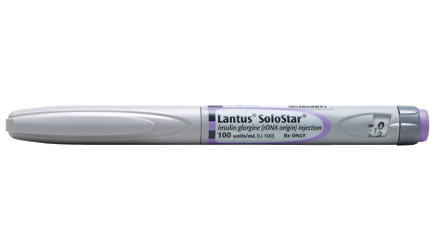

Securing approval for follow-on versions of branded insulin analogues like Sanofi’s long-acting Lantus (insulin glargine), which had 2012 US sales of $3.9 billion and loses patent protection in 2015, won’t be enough, the researchers say, because doctors’ standards are likely to be higher than regulators’.

“Today there is quite a big disparity between what the EMA wants, what the physician wants and what the FDA wants,” said Kate Keeping, biosimilars research director at BioTrends Research Group, which surveyed 90 endocrinologists and 90 nephrologists.

Endocrinologists are typically the most wary of biosimilars, she said. “They’re treating both pediatric and adult patients. They’re treating patients chronically and don’t want to switch patients already well-managed on existing branded insulins, so convincing them to use a branded biosimilar will be extremely challenging, unless [drug makers] have robust clinical data.”

That suggests regulatory guidance is merely a floor, but not a ceiling. Draft guidance from the European Medicines Agency (EMA), for instance, essentially says the regulator does not expect efficacy trials to be required for insulin analogues.

To feel comfortable prescribing the follow-on meds, clinicians will want extensive efficacy data from multiple Phase III trials, involving in excess of 1,000 patients, according to the report.

Various biosimilar versions of recombinant insulins are creeping toward market. Lilly jumped into the diabetes glargine biomsimilar pool, submitting its experimental drug to the EMA , along with partner Boehringer Ingelheim, last July. Merck has been rumored to have such a product in the works, and partners Mylan and Biocon are also in the running.

Lilly and Boehringer have done a full Phase III trial for their glargine treatment, LY2963016, in a large group of patients with type 1 and 2 diabetes, giving them flexibility for a US submission as well.

In the US, from 2020 insulins could be approved under a biosimilar pathway (guidance has yet to be finalized), but at the moment they’d need to be cleared under an NDA pathway. There’s some speculation whether it’s possible to use a 505(b)2 pathway.

“It looks like [Lilly/BI] will go the full NDA route,” said Keeping. “Obviously, Lilly is already a big player in diabetes anyway [although it lacks a long-acting product], so that product could do better than a biosimilar that’s only done what’s required by the EMA.”

By 2022, she added, BioTrends expects non-innovator versions of insulin glargine to capture combined patient share of 16% in the total US insulin glargine market. Lantus would hold the remaining 84% patient share.

The Bernstein analyst Tim Anderson has forecast biosimilar erosion of Lantus beginning in 2015, with the product dropping from a peak of 7.3 billion euros in 2015 to 4.7 billion euros by 2020, a 35% drop. “This erosion could accelerate more quickly contingent on the number of biosimilar producers,” he wrote in an investor note.

Other companies looking to develop biosimilars of branded analogues, which also include Sanofi’s Apidra, Novo Nordisk’s NovoLog, and Lilly’s HumaLog, must carefully design the clinical program to ensure they meet endocrinologists’ stricter expectations, Keeping advised.

While there’s limited information on what other companies’ biosimilars programs will look like, “Major players in insulins,” she said, “can expect a similar comprehensive clinical development program.”