In a closely watched yet surprising move, the Food and Drug Administration Monday approved the first drug designed to slow the cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer’s disease. The thumbs-up for the drug, aducanumab, means that patients suffering with Alzheimer’s-related dementia – who number in the millions – finally have a new option after nearly two decades without a novel treatment.

Many stakeholders expected a rejection. In fact, that’s what the agency’s own outside advisors had counseled in their highly critical review of the drug last fall. The drug’s clinical trial data left the door open for ambiguity, with two large trials halted prematurely. Only one of the two met the primary endpoint of clinical decline, albeit in a subset of high-dose subjects.

Aducanumab may have snared a coveted first-in-class designation, but the regulatory decision signals that it’s far from perfect.

“While this is an important first step in the fight against Alzeimer’s, it’s just that: a first step,” said Dr. Patrizia Cavazzoni, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), on a call with reporters Monday.

Indeed, in approving the monoclonal antibody, which will be marketed in the U.S. under the brand name Aduhelm, the FDA went against its advisors’ recommendation – a true rarity. Ultimately, the agency opted for a kind of conditional approval based on the evidence that aducanumab improves a “surrogate endpoint,” reducing the level of amyloid plaque in the brain. It’s pending more data to confirm the expected impact from that plaque reduction on clinical benefit.

“We listened to and carefully considered the needs of the people living with this devastating, debilitating and incurable disease,” said Cavazzoni. “The data supports patients and caregivers having the choice to use this drug.”

Nonetheless, ambiguity over the drug’s efficacy led to deep skepticism among physicians and scientists, with some warning beforehand that an aducanumab approval could undermine the agency’s credibility. Cavazzoni defended the integrity of the review team and of the FDA itself. The data package was the subject of a “broad, diverse and vocal set of stakeholders,” as she put it. “It’s not unusual – in fact, it’s expected – that different views of data in a development program will arise and will be discussed before a decision on an approval is made.”

Another surprising aspect of the decision involves Aduhelm’s label – which, it turns out, is written more broadly than many expected. The approved indication is for “treatment of Alzheimer’s,” rather than stipulating use of the drug only in patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild Alzheimer’s.

“It’s not expected that [aducanumab] would only be relevant necessarily at the early stages, because amyloid is a key part – a hallmark – of the disease through its entire course,” explained Dr. Peter Stein, director of the FDA’s Office of New Drugs, also on today’s media call. “And the expectation is that this drug would provide benefit across that spectrum.”

Due to what the FDA acknowledged was “residual uncertainty,” however, Biogen must still run a confirmatory trial, as required under FDA’s so-called “accelerated approval” pathway. “If this drug does not demonstrate benefit, we will move quickly within our authority to…remove [it] from the market,” Stein added.

The approval marks the culmination of decades of research – and untold failures – into targeting amyloid beta plaques in the brain as a strategy to disrupt the progression and slow the functional decline from Alzheimer’s-related dementia. As such, it was hailed within some quarters of the patient community.

“After so many disappointments in potential treatments, the Alzheimer’s community now knows this deadly enemy has finally been engaged,” noted George Vradenburg, chairman and co-founder of patient group USagainstAlzheimer’s, in a statement. “At long last, science and time are on our side. Patients in the early stages of the disease will engage with their physicians to learn what can be done, with early detection, to slow their cognitive decline and this disease.”

The label includes a warning for amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), which can lead to temporary brain swelling. The ARIA is “manageable” and incidence of severe events infrequent in the clinical trials, said Stein. “Even considering the residual uncertainty, we believe [the drug’s potential to stem the loss of memory, judgment and thinking linked to the disease] outweighs the manageable risk with respect to ARIA, and we heard very clearly from patients that they are willing to accept some uncertainty.”

The approval gives a much-needed boost to Biogen, which had been counting on aducanumab to stem erosion of its product revenues, largely due to generics and other threats.

“The rest of [Biogen’s] business is essentially a melting ice cube, either because of generic pressures (e.g., Tecfidera)… or competitive threats to in-line franchises (like Spinraza),” wrote the biopharma analyst Tim Anderson, of Wolfe Research, in an investor note. “Without an Alzheimer’s disease drug to sell, [Biogen’s] revenues and [earnings per share] have looked set to contract by a meaningful amount for a prolonged period of time.”

What’s still unknown, Anderson observed, is how quickly aducanumab sales will ramp up, how accommodating payers will be, and whether or not physicians will embrace the drug, given the controversies. Payers, he noted, may have a hard time saying no, yet coverage depends on the product’s price.

Biogen on Monday set the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) of Aduhelm, which is infused monthly, at $4,312 per infusion for the average dementia patient. That amounts to an annual cost of $56,000 for the 10 mg/kg maintenance dose.

The sum is far above what the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) assessed as fair value pricing – between $2,500 and $8,000 a year per patient – although Biogen CEO Michel Vounatsos vowed no price hikes for the next four years.

Given that many patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s are older, Medicare may be the main payer. “What CMS ultimately determines is uncertain, but the agency will be under pressure by many stakeholders to support access to the drug,” Anderson wrote.

That said, Biogen and private insurer Cigna today announced plans to enter into a value-based contract to ensure access, and that the parties intend to track pay-for-performance outcome metrics.

“Given the known infrastructure challenges in the U.S., we are working to ensure that the patients who will benefit most from this new treatment have a clear path to access it,” said Cigna EVP and chief clinical officer Dr. Steve Miller in a statement.

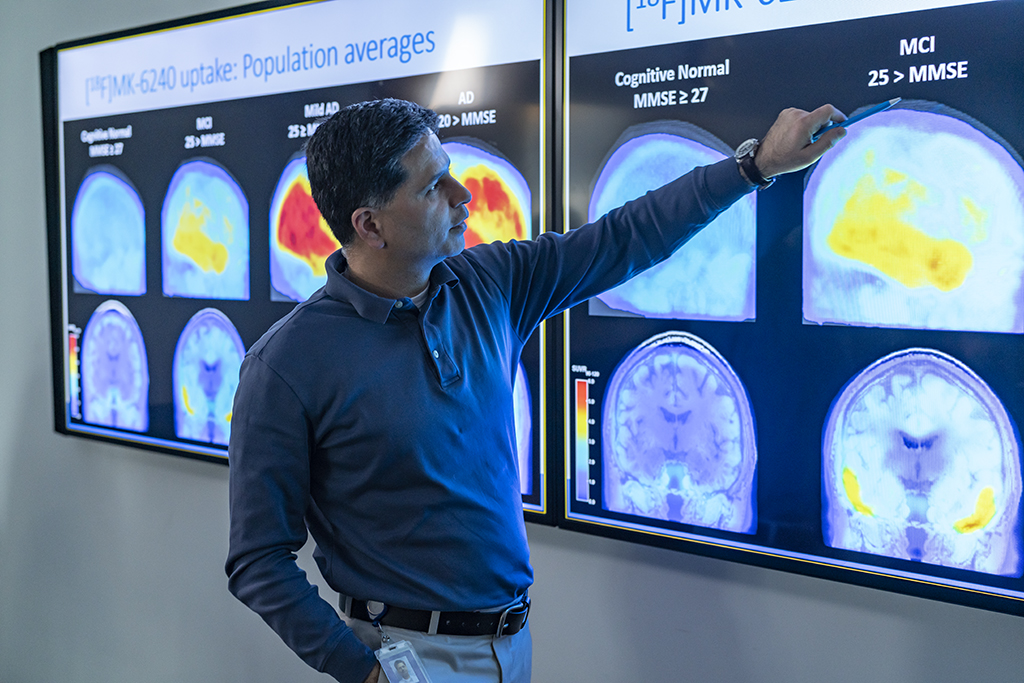

Those challenges include logistical kinks, such as the need for patients to demonstrate the presence of amyloid through PET scans, which are not reimbursed by Medicare.

“These sorts of bottlenecks will gate the initial uptake of the product, but as they are worked through, we ultimately expect this will be a massive market, ultimately rivaling immuno-oncology in size,” noted Anderson, who forecasts Aduhelm peak sales of around $17 billion in 2024 before starting to ebb in 2025. That’s when launches from rival drugs like Roche’s gantenerumab, Eisai’s lecanemab and Eli Lilly’s donanemab could begin to bite into sales. (All of these are still experimental.)

Drugs that target amyloid beta are likely to be only marginally effective – which is why, from a marketing perspective, clinching first-mover status was ideal for Aduhelm. What’s more, that clinical profile won’t necessarily hold back other drugs in this class.

“Alzheimer’s is a many-million patient disease where there is a substantial fear factor and a tremendous burden, not only for patients but for their caregiver families,” explained Anderson, “[That means] even modestly effectively drugs are likely to sell well, just as current symptomatic drugs do that barely have a clinical effect (e.g., Aricept).”