The year 2022 brought with it a host of sweeping healthcare changes, including long-awaited drug pricing regulation in the Inflation Reduction Act and abortion bans in the wake of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade. And the great majority of those changes occurred as the nation was beginning to emerge from a pandemic haze, as it took until September for President Joe Biden to declare, quite succinctly, “the pandemic is over.”

The pandemic is not, in fact, over, at least not as far as the World Health Organization is concerned. But as the clouds of the emergency phase of COVID-19 continue to clear — and masks and restrictions retreat further into the background — they prompt another question: What’s next?

After all, 2022 proved one of the most policy-rich years in recent memory, even though little true movement was expected during a midterm election year.

“Perhaps surprisingly, 2022 was a year where actually a lot was done in health policy,” says Jon Bigelow, the outgoing executive director of the Coalition for Healthcare Communication.

The year 2023 is shaping up to be quite different, with fewer monumental legislative packages expected to be proposed, much less passed. After the midterm elections, Congress is split. The early-December runoff in Georgia will determine whether the Democrats hold a 51-49 advantage in the Senate or a 50-50 one by virtue of Vice President Kamala Harris’ tie-breaking vote. The House turned red, though by a narrower margin than most pundits expected.

What that means: more partisan strife and gridlock in Washington, and almost certainly fewer tangible results on the health-policy front.

“The bottom line is that very little will happen, regardless of who’s in the nominal majority,” says Terry Haines, founder of healthcare consultancy Pangaea Policy. “What you’re going to end up with on the legislative front is status quo for the next two years.”

Thus with fewer ambitious COVID-era omnibus bills and a divided Congress, it will be near impossible to enact individual pieces of healthcare policy as legislation. And for the first time in a decade, one existing piece of legislation will be left alone: “You’re not going to have Congress constantly discussing whether and how to make major changes to the existing healthcare system and the Affordable Care Act,” Haines says.

But even if nothing monumental makes it into legislation, it shouldn’t be a quiet year on the policy front. Health priorities, such as further drug pricing regulation, abortion rights and mental health legislation, will remain on Democrats’ radar. Republicans, for their part, may focus some attention on telehealth, the opioid crisis and an investigation of the nation’s response to COVID-19.

For drug pricing, the Inflation Reduction Act gave Medicare the authority to negotiate prices on certain drugs — 10 starting in 2026, and up to 26 in 2029. It also capped out-of-pocket prescription costs for Medicare beneficiaries at $2,000 beginning in 2025.

Alas, prices continue to rise. That’s why there’s still plenty of interest among lawmakers — on both sides of the aisle — and the public to push for additional pricing regulation. To that end, some 50 public health advocacy groups recently called on Congress in a letter to address high insulin costs.

President Biden also tasked Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra with devising a list of administrative steps that could be taken to further reduce drug costs. In October, Becerra stressed that he wouldn’t take any pricing reduction options — including the invocation of march-in rights, which would allow the federal government to issue patent licenses for a given product to companies other than the one that owns the patent, in instances where the R&D was federally funded — off the table.

Still, Bigelow says that Democrats aren’t likely to have enough strength to make significant legislative moves in areas of priority to them, such as expanding the number of drugs covered under Medicare negotiation.

That’s why he believes further action on drug pricing regulation will occur “behind the scenes,” particularly in the regulatory realm. The Centers for Medicare Services will determine how exactly to implement the current Medicare negotiations and how to define which drugs will be chosen.

There are also plenty of policy issues on the Food and Drug Administration’s plate heading into 2023. While the appointment of Dr. Robert Califf has calmed the waters at the agency after a tumultuous few pandemic years, he has yet to execute on several of his goals and promises.

One is improving the accelerated approval pathway, an issue that has been on the policy radar ever since the agency approved Biogen’s controversial Alzheimer’s drug Aduhelm with what many experts believed was scant evidence for its benefits.

At the moment, Califf’s goal to fine-tune the accelerated pathway — and tighten up regulation to avoid approving drugs that don’t have enough compelling evidence — is “somewhere between vague statements and hard action,” Bigelow notes. The FDA recently recommended that Makena, intended to reduce the risk of preterm birth, be withdrawn from the market. That could be interpreted as a first volley toward reforming the process, and Califf is expected to make additional moves around changing the pathway in the months ahead.

Access to safe abortion was one of the biggest issues motivating voters during the midterm elections, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll (see p. 10). While abortion rights will undoubtedly remain a top healthcare priority for Democrats in 2023, even President Biden has notes that congressional Democrats won’t have enough votes to pass a bill codifying Roe v. Wade.

So the onus now lies on states to determine the future of abortion access. The midterm election results offered a mixed bag: Five states, including Vermont, Michigan, Montana, California and Kentucky, voted to protect reproductive rights during the midterm elections. Others had previously moved to further restrict abortion.

“This is fundamentally up to the states to figure out,” Haines acknowledges. “The federal government is going to have to reform its support around whatever individual states decide.” He added that the likely result will be something akin to “some kind of crazy quilt.”

Even without definitive federal action, Ogilvy Health EVP Monique LaRocque expects the battle over abortion to continue — and profoundly impact the world of healthcare marketing.

“We’re going to have more and more states doing things to either protect or take away those rights,” LaRocque explains. “As these rights are being taken away from women, men have a responsibility to step up in that game as well — and companies need to help create

more solutions.”

The abortion debate signals a broader overarching theme for the coming year: States could make strides on health policy if the federal government finds itself mired in partisan bickering.

“If the federal government can’t develop bipartisan policies that address people’s needs, state government officials are taking hold of the wheel,” Gil Bashe, chair of global health and purpose at Finn Partners, says in the wake of midterm election results.

Mental health will also remain top of mind. Late last year, Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy issued an advisory declaring a mental health crisis among young people. Rates of anxiety and depression rose significantly during the pandemic, with 44% of high school students reporting that they felt sad or hopeless between 2021 and 2022, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

At the same time, the U.S. faces a shortage of psychiatrists and other mental health care providers, and is struggling to meet demand. There were some efforts to pass legislation that would address mental health issues, including draft legislation that would tackle the shortage of workers and a bill aiming to improve mental health parity. But even though there is “a great deal of sympathy on both sides of the aisle for wanting to do things on mental health,” as Haines puts it, all such legislation is likely to fail due to a potential funding shortfall.

As for the areas where there could be action in 2023, policy experts point to intensified attempts to battle the opioid epidemic, investment in the development of new antibiotics to battle antibiotic resistance (including the Pasteur Act) and another push to shore up data privacy.

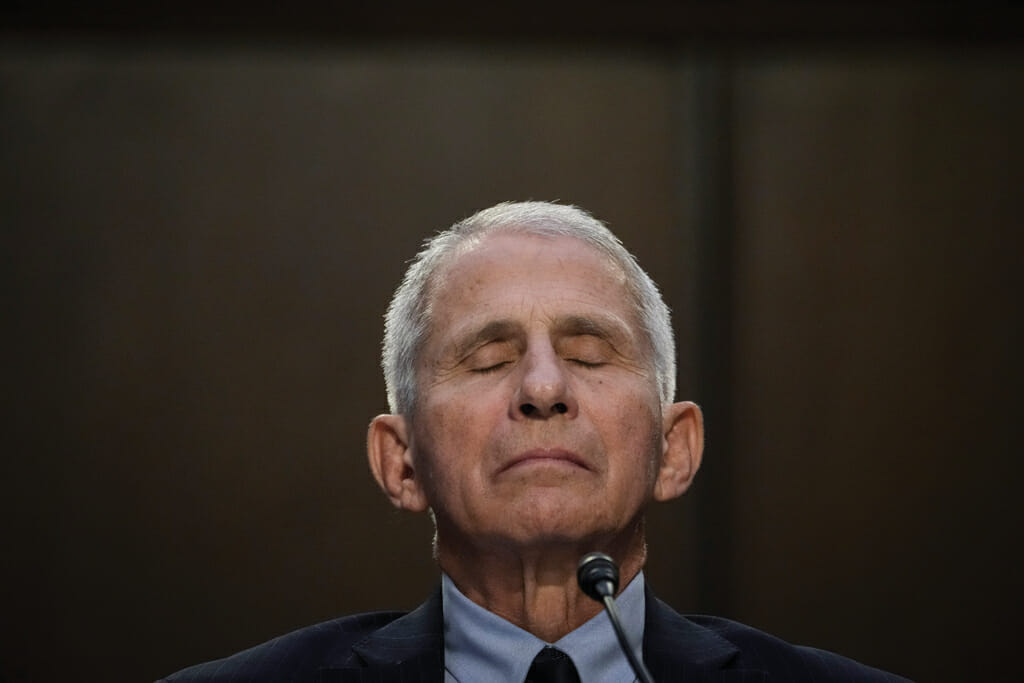

But as the Biden administration and the CDC try to revamp the federal government’s approach in advance of the next pandemic, Republicans will likely push back with calls to investigate Dr. Anthony Fauci as well as the origins of COVID-19.

“It’s crucial that we become more prepared, but very little progress is likely to be made,” Bigelow says. “It will get tied up in all these hearings about who is responsible for COVID-19. There’s going to be a lot of focus on things like whether the virus was created in a lab, instead of focusing on what to do about the next pandemic.”

Furthermore, funding for further COVID-19 aid and new rounds of vaccines, at-home tests and treatments has essentially run out. Congress has struggled to secure new funds in recent months, and isn’t likely to have any success with each party controlling one house.

“We’re going to be even less prepared if there’s another wave of COVID-19, let alone any new pandemics,” Bigelow says. “We’re playing with fire by not doing something.”

But pandemic fatigue is real — and LaRocque believes that lessons were learned over the course of the challenging last few years. She notes that the pandemic highlighted the need for, among other things, better mental health policy, and adds that the post-pandemic transition could prompt a focus on overall wellness.

“We have been through a lot. People are struggling and their mental health is strained,” LaRocque notes. “But we’ve also been awakened to things that we should have been paying attention to a long time ago. I feel like 2023 is going to be a breakout year, because people want more again. They want to move from just surviving to thriving.”