Terri Passick has spent much of her professional life attempting to match people with jobs. Now, with the help of an all-star team of industry colleagues, she’s trying to engineer a far more complicated match: herself with a kidney donor.

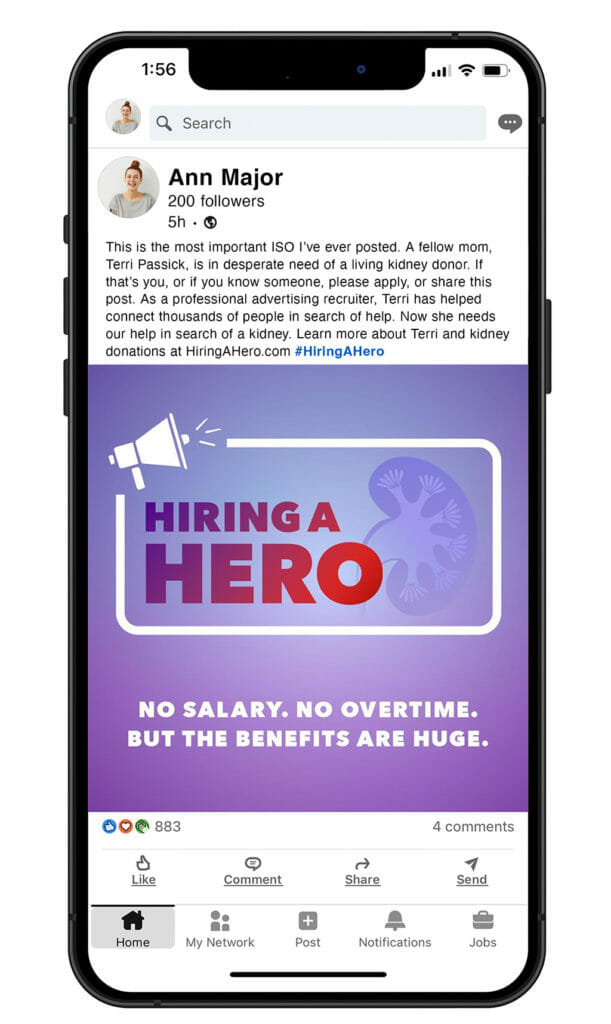

Their effort, “Hiring a Hero,” pairs traditional medical marketing techniques with the recruitment savvy that has made Passick one of the industry’s best-regarded talent execs. It unites higher-ups from nearly every one of the agency world’s biggest networks — Havas, IPG, Omnicom, Dentsu and WPP — with a host of independently owned shops and freelancers under the banner of “Friends of Terri.”

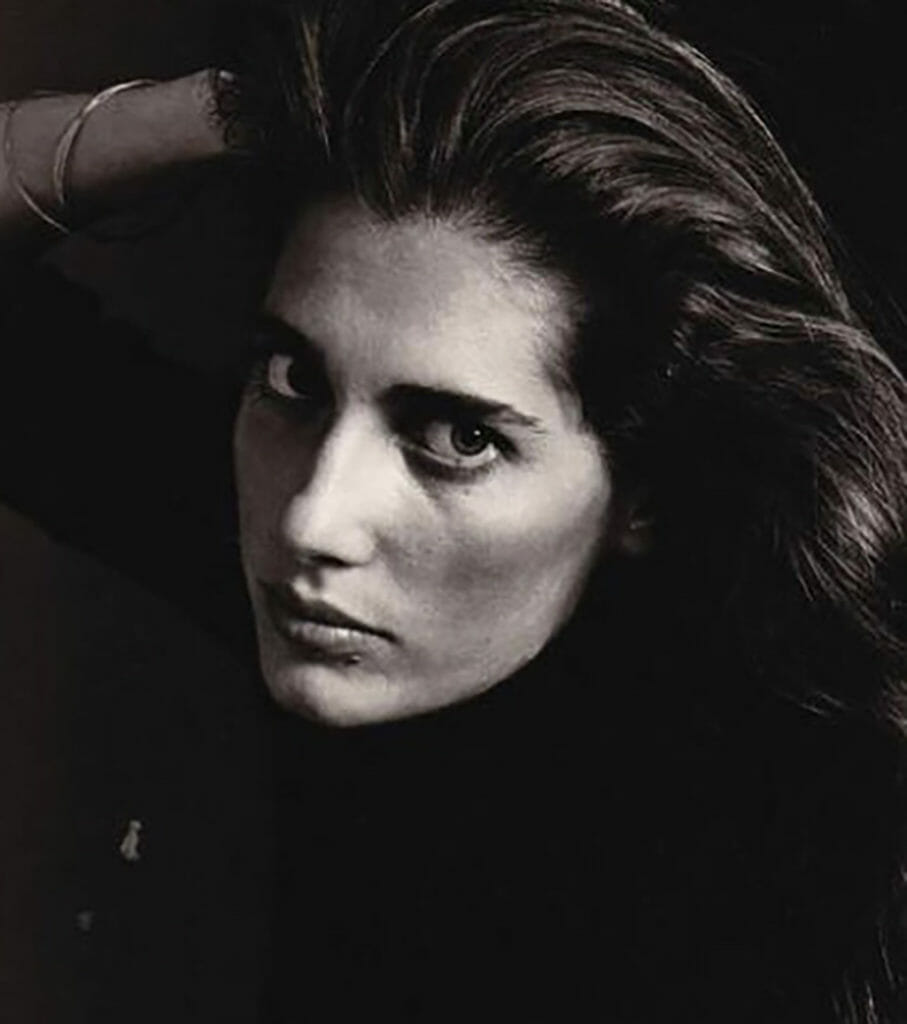

Passick, a 30-year industry veteran currently serving as SVP, talent acquisition at Havas Health & You, learned early in life that she suffered from Alport syndrome, a hereditary disease that damages kidney function. The condition cut short her father’s life before he turned 40.

Over the years, Passick learned to live with it. She participated in a host of drug studies — some short-lived, some several years long — and carefully monitored her physical condition.

“It was always in the back of my mind, but I never really concerned myself with it,” she said. “I didn’t feel like I had a lot to worry about — and I’m someone who always worries about everything.”

That changed recently when a promising drug failed to secure Food and Drug Administration approval. At that point, Passick’s physician said that she needed to start thinking about securing a transplant.

“When the news went from ‘Everything’s fine’ to ‘We need to talk about a donor,’ we started talking,” recalled Gary Scheiner, EVP, executive creative director at CDMP and the person coordinating the multi-agency effort. “As a friend you ask, ‘I’m terrified, how can I help?’” but Terri kickstarted it: ‘I’m in advertising and this is what we do for a living. We motivate people. We break through the clutter.’”

Even given the emotional nature of the assignment, the 20-strong team of Passick’s colleagues past and present approached it as they would any other. The group started with a creative brief and brainstormed ideas individually before reassembling as a unit.

“We didn’t have a paying client, so we had to be scrappy,” Scheiner explained. “Ultimately we took our inspiration from Terri. She’s a matchmaker; she finds the right person to fill the right role. So the idea is we want somebody to step up and say, ‘I want this job. I want to be the donor.’”

One rejected idea for “Hiring a Hero” took the job-search concept to an extreme. The team batted around the possibility of creating a CGDO role — chief good deed officer — either at Havas or elsewhere.

“You would have filled the role by donating a kidney, but then you would go out and talk about all the amazing things this industry does for all kinds of causes,” Scheiner said. “But at the end of the day, you can’t buy somebody like this. Also, who’s going to leave their job?”

Ultimately the group settled on the “Hiring a Hero” moniker (“I’m not sure I love the ‘hero’ aspect, but the alliteration works nicely,” Scheiner quipped) and a smart, pithy burst of campaign copy: “No salary. No overtime. But the benefits are huge.”

While members of Team Terri set about engaging their own personal networks, the “Hiring a Hero” push had to aim more broadly. To that end, they engaged with Renewal, a nonprofit that facilitates kidney transplants, as well as with networks of recruiters and working mothers.

“We wanted to encourage people to do what they do best, which is network,” Scheiner said. “These groups in particular are so good at helping each other: You need a babysitter for your kid, you need a dog walker, whatever — that’s where you reach out.”

As opposed to page views or Rx starts, the success of “Hiring a Hero” hinges on a specific and not easily attainable metric. That said, Passick’s work — on both her job and the broader kidney push — has had a palliative effect.

“Work has been a godsend during this situation,” she said, noting how closely the two efforts mirror each other. “Some days, it’s crickets. On other days, all of a sudden everyone’s reaching out. This is just a recruiter’s life.”

Passick said she is currently feeling “worn down,” but that she has “no pain, no real discomfort.” The donor process is playing out anonymously; if someone volunteers and passes the required physical and psychological screenings, Passick won’t be notified until about a week before she heads into the operating room. For all she knows, multiple donors could already have volunteered and qualified — and backed out last-minute.

That lack of transparency makes a hard situation even harder. “It’s the most awkward thing to be asking somebody,” Passick said. “I’m not just asking someone to do me a favor. It’s a crazy, crazy ask.”

She remains blown away by the raft of support, both from her colleagues and the broader industry.

“I don’t want to think about the kidney all day long, and they’re making it so I don’t have to,” she continued. “I don’t know how to thank them, but I’m so incredibly grateful.”

Learn more about Passick’s journey and the donation process here.