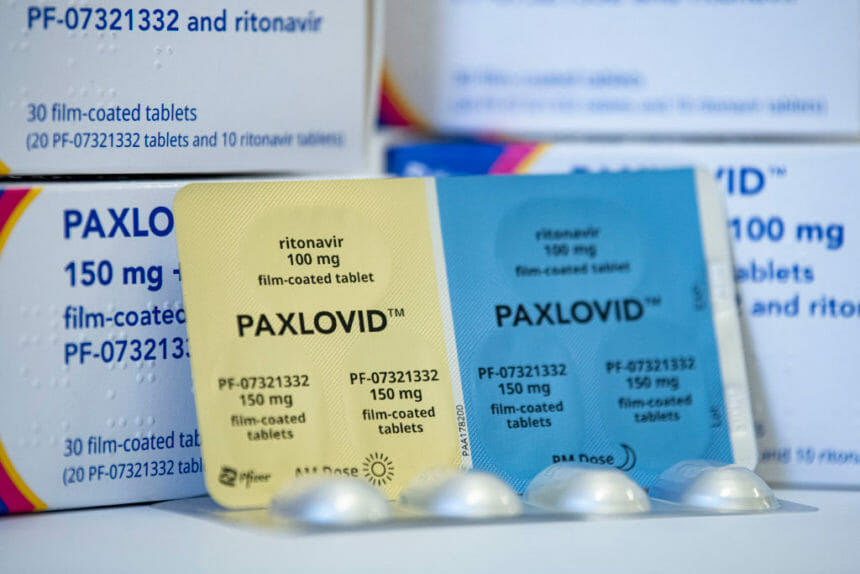

A new study is sure to add another layer of intrigue surrounding Pfizer’s COVID-19 pill Paxlovid.

In the study, based on data collected from 109,000 patients at a large Israeli health system, the drug appeared highly effective in seniors. Researchers found that those 65 and older who got the drug shortly after infection had a roughly 75% lower chance of being hospitalized, a rate which is consistent with earlier results.

However, those markedly decreased odds of hospitalization were not seen in the 40-64 age cohort, where researchers reported “no evidence of benefit.” That was the gist of their study writeup, which appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine, and the storyline was duly repeated countless times in mainstream media coverage.

Yet the antiviral drug’s benefits were nearly as profound in younger adults who weren’t immunized, a wrinkle which most of the headlines left out. In patients 40-64 years old without previous immunity (i.e., those who hadn’t been vaccinated and/or boosted), the benefit seen was 77%, which is on par with that observed in seniors.

In other words, without vaccination, the drug seemed to work better in both older and younger adults.

This finding suggests that Paxlovid still “could have a benefit in the high-risk group of those under 65, who tend to be hospitalized,” explained Dr. Reynold Panettieri Jr., a pulmonary critical care physician and professor of medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, who was not involved in the study.

Indeed, the jury is still out as to whether it has benefit in reducing hospitalization in that younger patient group.

“The truth is that it worked much better in those 65 and older,” said Panettieri. “But if you look at the sub-analysis and one wonders, ‘Can Paxlovid have an effect?,’ the answer is ‘Yes.’ The drug actually decreases the hazard ratio specifically for those who never got boosted before or were immunized.”

The study adds to the growing body of evidence around Paxlovid, which has been heralded since its authorization by the Food and Drug Administration late last year. In that time, the pill has been prescribed to treat certain patients who are at a higher risk of developing complications from COVID-19.

One mystery surrounding the drug has been its potential link to the incidence of so-called ‘COVID rebound cases.’ No less than President Joe Biden, First Lady Jill Biden and NIAID director Anthony Fauci have each suffered a relapse in symptoms after taking a full course of the oral treatment in recent months.

Pfizer brass suggested in an interview with Bloomberg in May that patients whose COVID symptoms relapse should take a second course of the antiviral pill. The FDA, which at the time said that Pfizer’s advice was not supported by data, has since asked the drugmaker to look into whether a second course can prevent the virus from returning.

The recent clinical data may also spur questions about the U.S. government’s reliance on Paxlovid, which has become a mainstay of the Biden administration’s test-to-treat program. The U.S. government has spent $10 billion to buy 20 million doses of the drug and in yet another sign of support, in July the FDA signed off on allowing pharmacists to write prescriptions.

But the administration may soon scale back its role in broadening access. The remaining federal supply is slated to run out by mid-2023, after which Paxlovid will transition to the commercial market, health officials have said.

As to why Paxlovid’s benefits were less clear-cut in younger adults than seniors in the Israeli study, Panettieri explained that the “incidence of occurrence [i.e., hospitalization] was different between the two groups,” and that it could have “potentially influenced the observation and the conclusion.” He added that it “might take 200,000 people to show the difference.”

That’s a statistical argument that’s beyond the interest of most lay audiences. The study was primarily designed to assess efficacy in both cohorts. Since the study missed its primary endpoint, the secondary outcomes couldn’t be analyzed, he said.

“But the data speaks for itself,” said Panettieri. “You don’t want to get into an argument in the lay press about that nuance.”

How will the findings affect patient access? The bottom line, he said, is that if you’re over 65, you should get Paxlovid. If you’re under 65, the study doesn’t support its use.

“However, the study has limitations, namely that the number of events in the under-65 subjects (those who were going to be hospitalized) was markedly less than over-65 and that could have influenced the results,” he said.

Additionally, the secondary analysis shows that in those not immunized, Paxlovid seemed to be beneficial in preventing hospitalization. That occurs whether you’re over or under 65.

“What I would like is not to say, ‘Unequivocally there’s no benefit in under-65,’” said Panettieri. “That’s an unfair statement.”