Drugmakers, distributors, doctors and pharmacies are all taking heat for their role in the opioid crisis, but the pharma industry, which is facing high-profile lawsuits and political pressure as the 2020 election nears, is taking the lion’s share of the blame.

High-profile lawsuits are a big part of the reason. In the past six months, lawsuits focused on pharma companies’ opioid marketing practices have made national headlines. Johnson & Johnson lost its legal battle with Oklahoma state attorneys in August, costing it $572 million. (The company is appealing). Purdue Pharma, Mallinckrodt, Allergan and Endo have reached settlement deals ranging from $15 million to $12 billion to resolve federal opioid lawsuits.

Pharma’s reputation is hurting, too. A September Gallup poll showed that pharma was dead last on the list of Americans’ views of major industries, behind even the federal government, oil and gas, and advertising and PR.

Gallup ranked pharma separately from the rest of the healthcare industry, apart from hospitals and insurers, which scored only slightly better at third from last. The poll attributed pharma’s poor grades to intense political attention on opioids and drug prices.

“I can see why the pharma companies are taking more of the blame,” says Srinivasaraghavan Sriram, associate professor at the University of Michigan. “It’s because there are few of them and you can identify them uniquely. For doctors, it’s a very amorphous entity and there’s no face. So it’s pretty hard to pin [healthcare’s reputation] down to any one person.”

Officials are focusing opioid policies on stemming the flow of drugs into hard-hit communities and expanding access to treatment while courts decide whether drug companies are responsible for the epidemic. Opioid overdoses killed more than 70,000 people in 2017, the most recent year for which data was available, and prescription opioids accounted for more than 35% of those deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

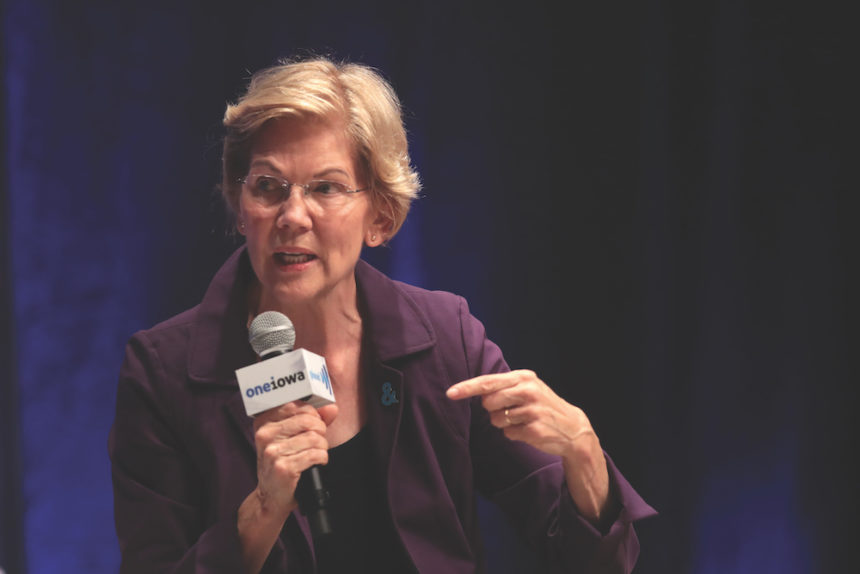

Dr. Yngvild Olsen, board of directors VP at the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), says expanding access to addiction services and training more doctors, nurse practitioners and physician assistants to treat addiction is a key element to combating the epidemic. Olsen, who is also an addiction medicine specialist, says the policy proposal to watch is the CARE Act, sponsored by Rep. Elijah Cummings (D-MD) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), which proposes a $10 billion investment over a decade. That money would provide funding to locations as needed, so they could establish addiction centers, train doctors on addiction medicine and expand access to opioid reversal drug naloxone.

I can see why the pharma companies are taking more of the blame. It’s because there are few of them and you can identify them uniquely.

Srinivasaraghavan Sriram, University of Michigan

“ASAM’s policy priorities fall into three buckets: teach it, standardize it and cover it,” Olsen says. “We recognize that the workforce is inadequate, and that’s the place to help millions of Americans. In 2017, there was an estimate that more than 21 million people actually needed treatment and only 4 million people were getting it. There is a lack of adequately trained and competent skilled clinicians that can really help provide evidence-based treatment.”

Congress has already taken actions including the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which was passed in 2016 to address the crisis through prevention, treatment, recovery, law enforcement, criminal justice reform and overdose reversal. Another important law was the SUPPORT Act, passed this year, which expanded government insurance programs to cover addiction and substance abuse treatment.

Pharma will likely be a political piñata for at least the next year. Democratic hopefuls for president have made healthcare — and opioids — central to their campaign messaging, and President Donald Trump has indicated he will make the epidemic a major theme of his re-election push.

On the Democratic side, Warren has carried the CARE Act into her campaign rhetoric. Other hopefuls including former Vice President Joe Biden and Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Kamala Harris (D-CA) say they would hold pharma companies responsible by imposing criminal fines and restricting marketing practices.

While lawmakers are grappling with addressing the crisis, the court cases are dragging on with a focus on the promotion of the drugs, specifically whether the industry’s marketing of opioids was deceptive or too aggressive. Sriram, who specializes in researching both healthcare advertising and the opioid crisis, says pharma “misrepresented” the risk of opioid addiction when used for chronic pain.

Another crucial step for the industry is education, says Craig Mait, president of Mesmerize Marketing, whose agency has worked on opioid awareness campaigns for both pharmaceutical companies and state health departments.

Governments are trying to reduce the number of opioids in the healthcare system, which are used by many patients to treat their pain. Campaigns that educate patients, pharmacists and doctors about the risks of opioids are key to both combating the epidemic and healing the healthcare industry’s reputation, Mait adds.

“It’s one thing to read an article about the opioid lawsuits, but it’s another thing to understand how that affects you or your family member,” he says. “It’s crucial to understand what that actually means and what that might mean for somebody that has a prescription for opioids or somebody whose family member may have one. The programs that we run are intended to help educate these patients with the information that’s necessary when they’re making their decisions about their healthcare treatment both at the pharmacy level and at the physician’s office.”

Educational efforts that would boost the pharma industry’s reputation would also target physicians. For doctors and pharmacists, education about how to properly prescribe opioids and what to warn their patients about when taking this type of medicine is the most important.

“We have very effective treatments [for substance abuse disorder], but we have way too few healthcare practitioners that actually can prescribe them and feel comfortable prescribing them,” Olsen says. “It’s one of those areas in medicine that healthcare professionals are going to see whether or not they’re actually the treating provider. So having some basic understanding of what do you do, how do you recognize addiction is incredibly important.”

Mait has worked on campaigns that educate pharmacists about prescribing naloxone, the drug that reverses overdoses, with opioid prescriptions and has educated doctors about how to properly screen patients before giving them powerful painkillers and even to cut down on their opioid-prescribing habits.

“Being in the medical space, being at the point of care, it’s an issue we are continuing to provide campaigns for,” he says. “We also have the capability to change behavior patterns both with physicians and the pharmacists. Is there a way for a physician who might have been a high prescriber of opioids to change that and look to alternative methods? Certainly. We look to combine those campaigns for patients, doctors and pharmacists together to raise awareness for what’s a huge issue in the country.”

Pharma’s efforts to mitigate the opioid crisis should focus first on prevention, like these initiatives to educate patients and doctors, then on correction, Sriram explains. For example, Purdue has provided tamper-resistant prescription pads to doctors and training about overdoses for law enforcement. Mallinckrodt, which makes generic opioids, supports new education for doctors about opioid prescribing and investing in alternative pain products and treatment plans.

Funding treatment programs and making naloxone more widely available are some ways the industry has tried to atone, but even that can draw backlash.

“Some pharma companies are trying to make [opioid antagonists] more widely available,” Sriram says. “In fact, Purdue Pharma came up with a more effective version of some of these opioid antagonists, but, of course, the criticism of that is these are the companies that created the problem and now they also plan to profit from this problem.”

From the October, 01 2019 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media