Modern medicine is moving at a breakneck pace, but in the race to bring better treatments to market, are we leaving the most vulnerable groups behind? In the U.S., Black people face the highest cancer mortality rates, and yet they are often left out of clinical trials that provide access to innovative new treatments.1,2

Cancer doesn’t discriminate. So why do clinical trials? To confront this question, IPG Health gathered an esteemed panel of clinicians and health activists for an illuminating discussion.

Uncovering the gaps in representation

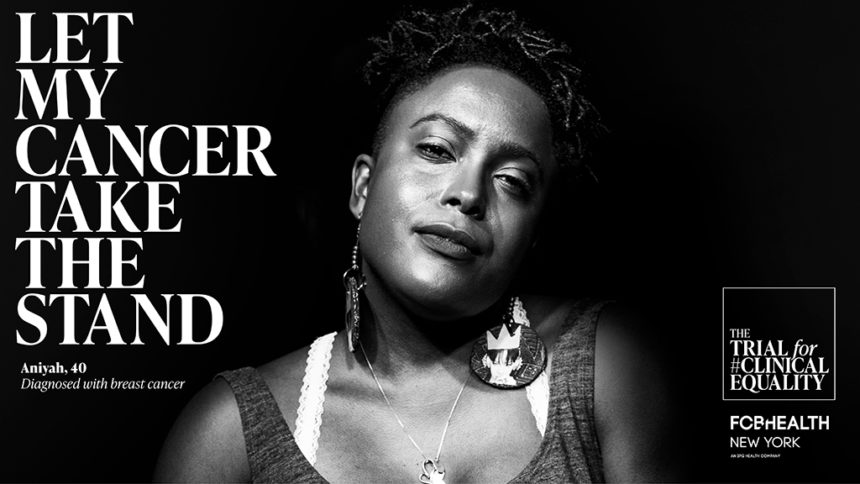

Clinical trial representation is a hot-button issue for Dr. Sommer Bazuro, global chief medical officer, and her team at IPG Health, particularly now as the conversation about racial disparities in health is gaining traction. To start a movement for change, they launched The Trial for #ClinicalEquality campaign.

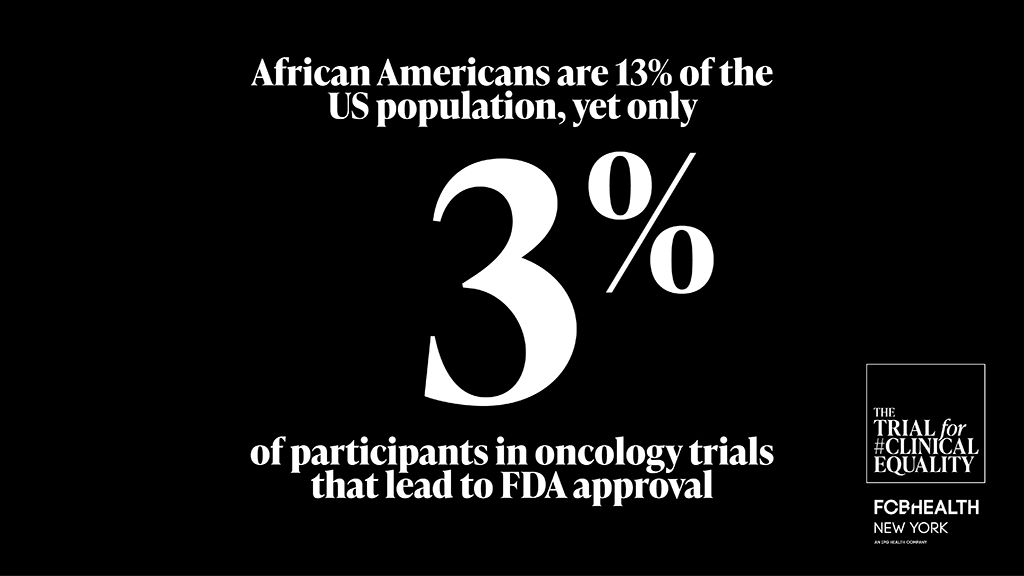

“I see clinical trials as a gateway to innovative therapy,” Bazuro explained. While reviewing clinical trial data in her role as chief medical officer, she noticed significant gaps: Black and Hispanic patients were underrepresented even in trials for cancers that disproportionately affect them. This presents both a moral and scientific issue. Cutting-edge treatment is not being offered to people who need it the most and conclusions are being drawn from incomplete data.

Ricki Fairley, a 10-year survivor of breast cancer and CEO of TOUCH, The Black Breast Cancer Alliance, put it quite simply: “[Black women] have a 41% higher breast cancer mortality rate than white women2,3… The only way we’re going to change the game on these statistics is to get drugs that are made for our bodies.”

Dispelling myths and misconceptions

Certain patients may be hesitant to participate in clinical trials because of preexisting misconceptions.

At Weill Cornell Medicine, Dr. Lisa Newman leads a research group that is focused on uncovering breast cancer disparities in Black women. She explained that any fears of being denied effective treatment as part of the research are unwarranted. “That is not the way clinical trials are conducted for cancer. It involves giving some experimental treatment that looks like it’s promising for being better than the standard of care compared to that standard of care.”

However, the notion that Black and Hispanic patients are more likely to decline participation in a clinical trial is a misconception in itself.

“Once African American patients were presented with trials, they were accepting of those clinical trials as much as their white counterparts,” Bazuro said, citing a recent study led by Dr. Joseph Unger of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.4 “It’s a matter of how it’s presented, and the information has to come from a person of trust.”

Understanding the barriers to participation

The barriers to participating in a clinical trial can be grouped into three categories: patient, provider and institutional barriers.

From a patient perspective, participating in a clinical trial requires a level of commitment that low-income patients of color may not be able to afford, especially due to childcare concerns, transportation costs and unpaid time off from work.

At the provider level, some doctors are not offering trials to their patients of color, potentially due to misconceptions about willingness to participate, as highlighted previously.

In terms of institutional barriers, clinical trials are often inaccessible to low-income patients of color because the trials are not being conducted in public hospitals.

“We have to invest in making clinical trials more accessible, in the breadth of hospitals, not just academic cancer centers, but also public hospitals, safety net hospitals,” Newman suggested.

Demanding legislative change

The good news is that the FDA has taken some initial steps to address racial representation in clinical trials.

“The FDA came out with some guidance to try and increase diversity in clinical trials. And that included addressing issues around accessibility,” Dr. Crystal Denlinger of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network said, before she laid out how some of this guidance may help to bring “the trial to the patient,” as opposed to vice versa.

However, Bazuro and her organization believe the solution also requires legislative change. “We hope that laws will mandate that all clinical trial demographics would align more closely with the incidence and mortality rates.” One such piece of legislation is the bipartisan DIVERSE Trials Acts, which, at the time of publication, is still being reviewed in Congress.

For Bazuro, the work has only just begun. “I hear anecdotally all the time, ‘oh yes, my mother had metastatic melanoma and she went to this research institution and got this and lived an additional eight years.’ I wanna hear more of that for everyone, not just a select group of people.”

Get the facts. Watch the full panel discussion on demand here.

To join the conversation, follow The Trial for #ClinicalEquality on Twitter and LinkedIn.

To take action, demand legislative change here.

1. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: Cancer Disparities. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/disparities.html [Accessed December 2022]

2. Loree JM, Anand S, Dasari A, et al. Disparity of race reporting and representation in clinical trials leading to cancer drug approvals from 2008 to 2018. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(10):e191870.

3. Richardson LC, Henley SJ, Miller JW, et al. Patterns and trends in age-specific Black-White differences in breast cancer incidence and mortality – United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(40):1093–1098.

4. Unger JM, Hershman DL, Till C, et al. “When offered to participate”: A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient agreement to participate in cancer clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(3):244–257