From where and how much we sleep to step counts and the timing of menstrual cycles, the prevalence of health apps and wearables has transformed us into walking collections of data points. According to a recent Morning Consult survey, about 40% of U.S. adults now use health apps, while 35% use fitness wearables.

The increasingly vexing problem? This data is not protected under the aegis of the Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act (HIPAA), which has created myriad opportunities for bad actors to use the information in ways its users never intended. In 2021, 61 million records from Fitbit and Apple fitness devices were exposed online. Similarly, the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision by the Supreme Court has further spread alarm about period-tracking apps, which already had a spotty data protection record.

The lapses have bred widespread mistrust. According to a 2022 Journal of Internal Medicine study, less than 15% of consumers trust companies such as Apple, Fitbit, Google and Meta with their digital health data. In a 2021 Deloitte survey, 60% of smartwatch or fitness tracker users said they were somewhat or very concerned about the privacy of their wearable data.

Some help is on the way, in the form of new state laws that aim to protect health data falling outside HIPAA’s purview. So as the government and consumers become more vigilant about protecting health data — and digital advertising writ large continues its vigil for Google’s long-delayed elimination of third-party cookies — how can healthcare marketers balance getting the information they need with consumer privacy concerns?

It largely comes down to transparency. “People understand that it’s OK to share their data, as long as they consent to it,” says Ogilvy Health senior director, marketing analytics Priyanka Prakash. “They need to be able to be in control of their data, regardless of where it is shared.”

If consumers feel there’s a lack of transparency around the use of their data, they’re more likely to opt out of any

information-sharing. This, in turn, will limit the ability of healthcare marketers to understand patient patterns and pain points.

“It’s a value exchange,” Prakash continues. “‘I’m going to be completely transparent with you about what I’m going to use this for, and you can hold me accountable.’”

However, a key part of transparency is presenting consumers with information in a way that they can actually understand. As Publicis Health chief technology officer Pete Walker points out, “There’s meaningful content in those seven-page Terms of Service, but nobody reads it. And that’s a real problem we all have to solve.”

Cobun Zweifel-Keegan, the Washington, DC, managing director of the International Association of Privacy Professionals, emphasizes that “good consent mechanisms” are a critical part of making sure that consumer data is “collected with care.” He points to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the European Union’s privacy law, which contains a long list of adjectives specifying what consent should be. The list notably includes “meaningful” and “informed.”

“Keeping that framework in mind often helps companies make mechanisms that are actually meaningful and able to be processed by people in the moment,” Zweifel-Keegan says.

He suggests considering multiple modalities of consent in order to meet consumers where they are, as well as “making sure that people can just as easily revoke the permission that they grant” — which is part of the EU law, not to mention several of the new state laws. Walker agrees, adding it is incumbent on medical marketers to make sure consumers know not just what data they’re using, but how and where it’s stored.

“How do we know that it’s in a secure place? How do you demonstrate that to a patient or to a user in a way that is meaningful to them?” he asks.

Zweifel-Keegan, for his part, points to the privacy centers now operated by many larger companies. Ultimately, he says, such above-and-beyond offerings allow consumers to “drill down on the settings that they’ve already enabled, and provide context about what the company is doing.”

By the time consumers reach a consent mechanism and are considering whether to share their data (and, if so, what kind of data), a strong base of trust should already be in place. “Once engagement with your content and returning interest occurs, we make sure there’s a place for them to raise their hand, share their information and be a part of the community, or just stay connected,” Prakash says. “Those kinds of opt-in avenues are really critical: Consumers volunteer the information, but trust has to be built before they do that.”

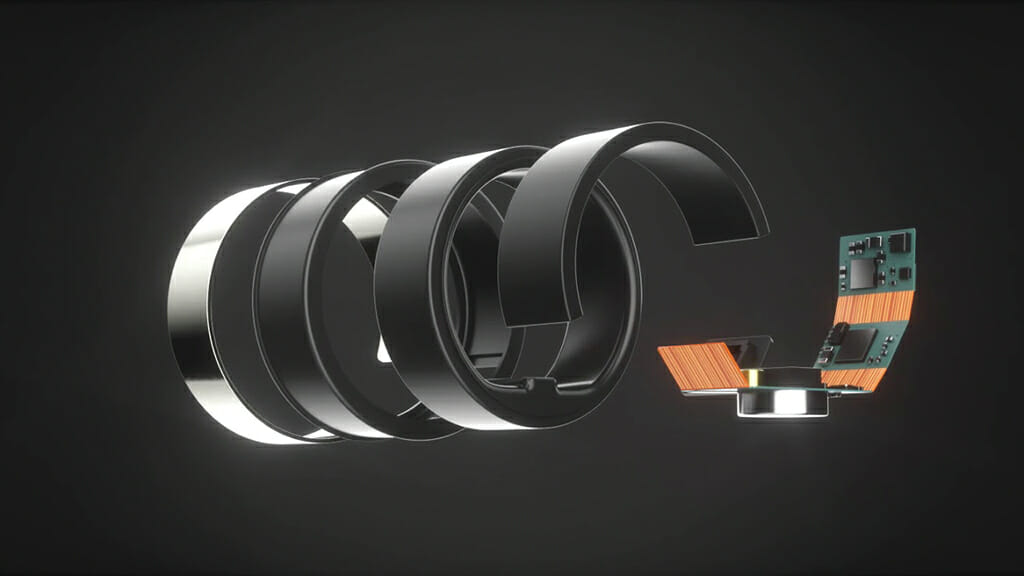

Building consumer trust through privacy protection is a key part of the business model at Circular, the maker of a smart ring measuring everything from blood oxygenation to the amount of REM sleep in a given night. “Data security does not directly create profit, and it takes time and sometimes a lot of monetary investment,” notes company cofounder and COO Laurent Bsalis.

However, he adds that “a serious company that wants to stay in the long-term must understand that the investment is mandatory. If not done, something bad will happen, and the reputation built up over the years will be wiped out in a single day.”

By way of example, Bsalis says that all of Circular’s users own their data and can choose to delete it at any time. The company believes this is simply good business practice: “Customers have begun to seek more control over their personal data. They value more and more transparency, clear consent processes and options to delete their data.”

As for the value exchange inherent in any data-related transaction, marketers need to make clear the benefits flow both ways.

“The benefit of sharing your location data with a weather app is that it will warn you when a tornado is coming. Likewise, with consumer health apps, the more granular the personalization you are affecting, the greater the value you need to return,” explains Ted Sweetser, director of sales success at PurpleLab.

He believes many individuals are more willing to share basic information that can inform segmentation (age, gender and the like) than constant daily health readouts (say, of EKG and blood glucose levels).

“Some wearables coming to market are actually approved for being able to detect arrhythmia. If you can help catch cardiovascular problems in advance, then you are really returning a lot back to the consumer for their data,” Sweetser adds.

Once consumers trust a company enough to share their data, it’s critical to follow through on protecting it through measures, such as tokenization.

“Nobody should be using personalized information,” Prakash stresses. “What’s relevant to us is the journey they’re on and the best action we can serve them next based on their digital actions — whether they saw an ad, clicked on content or downloaded a discussion guide.”

Walker adds that “an individual person at the Fitbit-step tier of data isn’t meaningful to us .… It’s not clinically validated. It’s trend data.”

What is valuable, he says, is data that is relatively static. For example, instead of knowing every step someone takes, it’s more helpful to know whether they’re trending in a positive or negative direction with their movement.

For the benefit of both marketers and consumers, it’s critical that marketers have a thorough understanding of the data they’re using — and actively monitor it. This, at least in theory, ensures that data partners remain true to their own best practices and principles.

“You must understand who your data partners are, ask to inspect them and ask to truly understand where the data comes from and how it flows,” Walker explains. “And then, once you have that roster out there, you need to do some critical audits, either every six months or every year.”

In a time when there is so much data available, it’s critical to focus on the quality rather than the quantity of data. “Having more complete data and confidence in the data is going to move the needle. Data is not valuable; insights are,” Walker adds.

Zweifel-Keegan agrees, but emphasizes that healthcare marketers need to be aware about the inferences they’re making about consumers from their data — and the inferences others could potentially make.

“Whenever you’re combining information from multiple sources, you need to be careful about tracking the new information created from that, and ensure that you’re able to find the original source of information and then track it down,” he explains. This scenario comes into play when consumers ask to have their information deleted, an option that is required under state privacy laws such as Washington State’s My Health My Data Act.

Even with first-party data, marketers need to remain vigilant. As Zweifel-Keegan notes, organizations “have to be careful not to reveal any information to a third party that could allow individuals’ health conditions or interests to be guessed by the third party.” This might require better anonymization of the data set, or triple-checking settings to make sure the third party can’t use the data for its own purposes.

Zweifel-Keegan also emphasizes that marketers need to pay attention to the changing definition of what actually constitutes “health data.” This has surged in importance as AI and other algorithmic tools have become more powerful and able to “make accurate inferences about people.”

“It’s not just conditions and medications, it’s anything that can be used to infer those things,” he says, pointing to the broad definitions of health data as outlined in the Washington state law and by the Federal Trade Commission. For instance, the FTC now defines biometric data as anything “that can be processed in a way that can determine someone’s unique characteristics, including raw images, video, audio and also body spatial data,” Zweifel-Keegan notes.

As for the organizations that get it right, so to speak, one name comes up again and again in conversations with privacy pros: Apple. “Apple has positioned itself as a trust company just as much as they’ve positioned themselves as a technology company,” Walker says. He admires the way Apple uses natural language to help consumers understand where their data is going, as well as the company’s transparency around the re-use and selling of consumer data.

“If privacy is the new safety, then Apple is Volvo,” Walker continues. “They’ve done a really good job pushing campaigns around security and privacy control, and I think that our whole industry could learn from that.” Prakash agrees: Apple’s approach to privacy and data security is “where this is all headed,” he says.

Of course, as the amount of data from wearables and apps proliferates, so too will consumer skepticism and government regulation.

“The ongoing responsibility for any company that has health-related data is to keep checking on privacy practices, and continuing to adapt in a way that recognizes that this is sensitive information that’s deserving of heightened safeguards,” Zweifel-Keegan says.

At the end of the day, Walker points out, healthcare marketers and consumers are aligned in their goals, and the responsible handling of consumer data represents a win for everyone.

“I believe that ‘marketing’ is a word that we’re going to start to walk away from, and it’s going to be more about care and support,” he says. “You can’t give care and support in an anonymous world. We need to share data back and forth.”