Among the myriad deficiencies in the U.S. healthcare system laid bare by the coronavirus, the profound lack of health literacy hasn’t received much attention. But even as misleading messaging in the early days of the crisis hamstrung many individuals’ understanding of the unfolding disaster, their inability to parse the language used by medical experts certainly didn’t help matters much.

This frustration has been expressed by any number of players across the healthcare system; it’s not news. That’s why, assuming some sense of normalcy eventually returns to the country, the larger healthcare marketing and communications worlds might want to take a cue from the smaller point-of-care one, which has been preaching the health-literacy gospel for years.

It’s been doing so with good reason. “The point of care is where the moment of actual engagement with the healthcare provider takes place, and where the implications of not understanding are most consequential,” says Kate Merz, EVP of content and creative at PatientPoint. “That’s where the health-literacy gap comes into play. Patients leave the doctor’s office confused and not knowing what to do next, and then they are afraid to ask questions because they don’t want to feel foolish.”

Mesmerize president and chief revenue officer Craig Mait agrees, adding, “Given the endemic nature of point of care, educational materials placed within this environment make it one of the most important channels to address health literacy. Educational resources offered at the point of care allow patients to become more knowledgeable about symptoms, disease states and treatment options, and overall better equipped to have an informed discussion with their doctor.”

Per the Affordable Care Act, health literacy is defined as “the degree to which an individual has the capacity to obtain, communicate, process and understand basic health information and services to make appropriate health decisions.” What that definition doesn’t include is the cascading effects of poor health literacy: For instance, what will happen if a patient doesn’t entirely understand the urgency to make changes to a diet or fitness regimen. Ignoring or misinterpreting such advice could lead to, say, a higher incidence of chronic illness — and the lost wages, diminished quality of life and lower life expectancy that can stem from it.

“People who aren’t health-literate are hampered in their ability to adopt healthy habits. They’re unable to make appropriate health decisions, ” says Health Monitor Network editor-in-chief Maria Lissandrello. “It has a real ripple effect.”

Not that anyone has an answer for the larger health-literacy problem, but executives who operate in and around the point-of-care space believe it can be a sort of breeding ground for more informed approaches. The place to start, most say, is in empowering patients to have better conversations with their physicians.

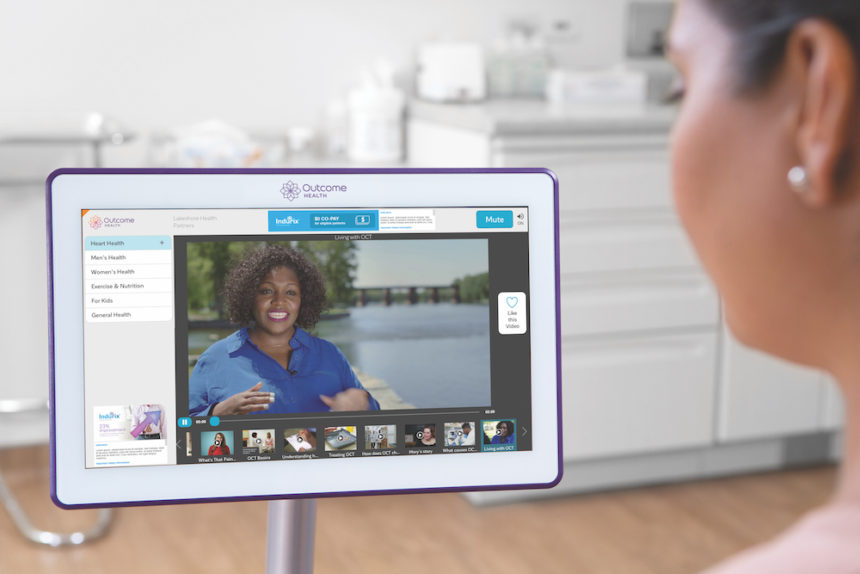

This can happen in a variety of ways, but the first step involves accounting for differences in the manner in which individuals learn. Older patients are said to respond most positively to text, while younger ones do best with visuals and videos. Then there are the so-called kinesthetic learners, who take naturally to the touch screens that populate many exam rooms. Quizzes/self-assessments and bulleted lists tend to work for point-of-care audiences independent of age or literacy level.

Patients leave the doctor’s office confused and not knowing what to do next, and then they are afraid to ask questions because they don’t want to feel foolish.

Kate Merz, PatientPoint

Health Monitor Network, which produces both digital exam room posters and print products, often looks to the consumer publishing and presentation models for inspiration. “When you’re trying to sell a magazine off a newsstand, you make sure you’re presenting the information in a way that’s viscerally appealing and charges that impulse to buy,” Lissandrello explains. “In the point-of-care setting, we’re trying to get people to buy the information itself. Long blocks of copy don’t really work.”

Some copy, of course, is necessary in almost any conveyance of information. To that end, direct addresses and the use of “you” go far toward personalizing any message and, by extension, forging a truer connection with low- and high-literacy individuals alike.

“You need to account for the fact that, in the healthcare space, there’s lots of jargon and lots of multisyllabic words,” Merz adds. “We know that doctors will always use them — so instead of steering patients away from the difficult language and terms, we need to explain them simply. That’s a big piece of the health literacy puzzle right there.”

This physician/patient connection, Outcome Health CEO Matt McNally says, is crucial given the stress inherent in any point-of-care engagement.

Some of the blame lies with the provider. They don’t always do what they can to ensure that a patient understands what they’re saying.

Maria Lissandrello, Health Monitor Network

“If you’re concerned about your health at home, you’ve got an infinite amount of access to health information. You’re Googling, you’re talking to Mary from down the street,” he explains. “But even for the most literate or best-read person, when you walk into the four walls of the doctor’s office, your stress goes up. The closest analogy I have is when you’re going through a fire drill versus when you smell smoke in a building. It becomes very real.”

That’s why the most critical component of health literacy might be the tools that empower patients to manage those conversations ably and without feeling intimidated. While patients are likely to remain deferential to providers and their advice — the notion of the “imperial physician” remains alive and well in exam rooms around the globe — they need to feel able to ask questions or otherwise push back.

Many execs feel that HCPs need to assume responsibility for, at a minimum, addressing literacy gaps among their patients. “I’m not sure I should be saying this, but some of the blame lies with the provider,” Lissandrello says. “They don’t always do what they can to ensure that a patient understands what they’re saying.”

That understanding can be bolstered during the physician visit via established learning techniques — including the “teachback” method, in which physicians ask patients to explain in their own words the advice or information they were just given. Understanding and literacy can also be strengthened via post-visit takeaways that “extend the experience and engagement beyond the point of care,” says Merz, whose company offers a product, PatientPoint Extend, that automates the sharing of educational materials following a doctor’s visit or hospital stay.

Such materials reinforce information and encourage higher literacy when it’s needed most: at the time when the patient needs to act upon the physician’s directives. It can be invaluable for the patient’s family and friends as well.

McNally recalls his experience providing care for his mother in the wake of a cancer diagnosis.

“When someone is given a diagnosis — whether for something not life-threatening, such as ADHD, or something very scary, such as stage-4 metastatic breast cancer — the conversation goes dark after you hear what the doctor tells you,” he says. “It’s like listening to the Peanuts teacher: Everything you hear is muffled. Materials for the patient and the support team can help you get past that.”

So while health illiteracy isn’t about to be eradicated overnight, successes combating it at the point of care suggest any number of potential solutions.

“The good news is that the concept is top of mind now, with government and health organizations mindful how the lack of health literacy can contribute to bad outcomes. There’s an understanding of the consequences for our health system,” Merz says. “Once you have that realization, you can start addressing it.”

From the April 01, 2020 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media