In 2013, GlaxoSmithKline made a decision that stunned and baffled its peers. The industry had once again come under fire for its promotional tactics, with some generating more heat than others. One that topped the list, improbably, was paying physicians, academics, and other medical-world influencers to speak before audiences of HCPs.

Never mind that much of the industry considered the practice to be benign, especially when compared with decades-ago tactics. The thinking among critics came to be this: Anyone paid to shill on behalf of any organization, brand, or disease state was inherently slanted toward whoever was picking up the tab. GSK’s decision was to announce, with no small amount of fanfare, it would cease paying HCPs to speak about its products and therapeutic categories.

The company made this decision expecting, perhaps, the rest of the industry would follow its lead. Nobody did. “It kind of took a moral stand,” says Mike Luby, founder, president, and CEO of the Biopharma Alliance. “If you talk to people who were there at the time, the belief was it was going to science up its reps to the point it wouldn’t need to pay opinion leaders to speak. But the response from everyone else was, ‘Good luck with that.’”

Tara Grabowsky, M.D., chief medical officer at HVH Precision Analytics, agrees. “GSK shot itself in the foot by taking away one of its most powerful tools vis-à-vis its competitors. It’s a fantastic company, but it miscalculated. Maybe people back [in 2013] didn’t think of it as a voice to follow,” she says.

Not surprisingly, GSK doesn’t quite see it that way. “An industry shift to the standards we announced in 2013 has not materialized. HCP feedback has shown they prefer to learn about new data through peer-to-peer programs with global expert practitioners who have direct experience with our medicines,” wrote Evan Berland, director, U.S. corporate comms, and interim head, U.S. digital, in response to emailed questions, using verbiage lifted from the part of GSK’s website explaining the company’s recent history regarding its paid speaking guidelines. “The effect of this has been that our educational programs have not been as widely available, or seen as compelling to HCPs, compared to other company programs. We believe this has led to a reduced understanding of our products and is ultimately restricting patients’ access to innovative medicines and vaccines.”

However, GSK does push back against the notion the no-paid-speaking policy placed it at a competitive disadvantage. “Under the previous policy, we developed medicines in HIV and respiratory that generated annual sales of more than $1.26 billion,” Berland noted.

Off-the-charts good

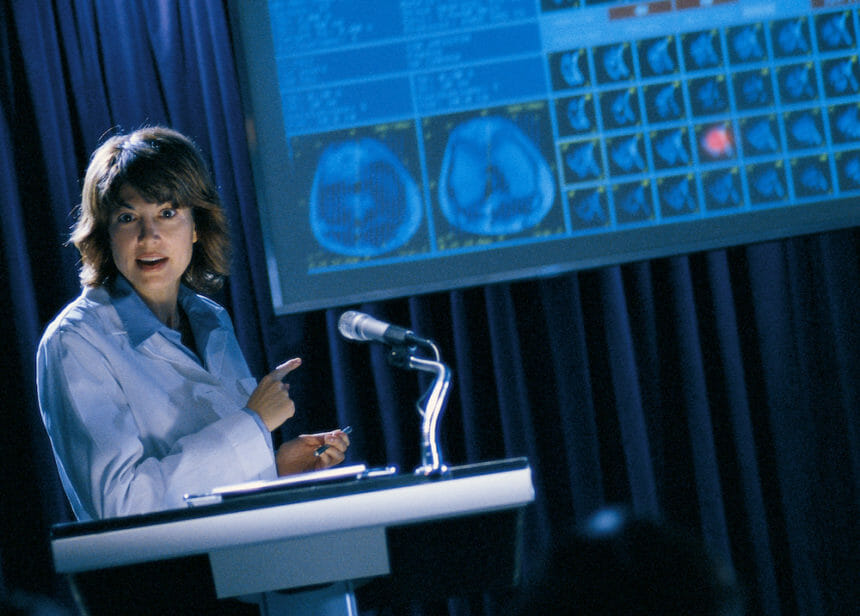

So here’s the thing about paid speaking programs: They work. Companies wouldn’t continue to spend so much money on them if they didn’t. Meanwhile, HCPs swear by their value, even when the klatches don’t come with the promise of an expertly tenderized prime rib.

This was as true in 2013 as it is today. Barring some complete reimagination of pharma marketing, it’ll be true in 2023, 2033, and beyond.

“The efficacy [of paid speaking] is off-the-charts good. In just about every case I can think of, it would be marketing negligence not to put huge dollars against this,” Luby says.

Even its critics acknowledge resources devoted to paid speakers are ones well spent. Adriane Fugh-Berman, M.D., is an associate professor in the department of pharmacology and physiology and in the department of family medicine at Georgetown University Medical Center, as well as the director of PharmedOut, described in her bio as “a GUMC research and education project that promotes rational prescribing and exposes the effect of pharma marketing on prescribing practices.”

The efficacy [of paid speaking] is off-the-charts good. In just about every case I can think of, it would be marketing negligence not to put huge dollars against this.

Mike Luby, Biopharma Alliance

Asked about the deployment of paid speakers, she responds, “It’s one of the most effective marketing strategies [pharma] has. Doctors trust their mentors and peers and most KOLs have the credibility that comes with being based in an academic institution.”

Which isn’t to say Fugh-Berman is a fan of the practice. “Unfortunately, it is not perceived as marketing by many people. It’s particularly effective because it isn’t perceived as marketing.” Nor is it regulated as such: Paid speaking is generally lumped under the CME umbrella, which spares it FDA oversight.

What gets lost in any discussion of these programs — and was especially absent in the schadenfreude-laden responses to GSK’s reversal a few months ago — is that paid speaking has evolved as an offering. Mary Manna Anderson, group president, medical education at Haymarket Media (the parent company of MM&M), recalls a time when speaking engagements underwritten by pharma were an entirely different animal.

“The doctors weren’t the only ones getting paid in some cases. Attendees sometimes got a stipend in addition to their dinner,” she says. “Plus, speakers presented with decks that weren’t necessarily locked. They could mix and match slides depending on the occasion and the audience and whatever they were trying to get across.”

Compare this with her description of today’s klatches. “All the information has to be approved by medical and legal. Speakers can’t editorialize. There aren’t salespeople stalking around,” Anderson continues. “It’s what it should be, which is an opportunity for doctors to come and hear information from an expert in an appropriate and efficient manner.”

An evolution in thinking

Grabowsky has experienced a similar evolution in her thinking about paid speaking programs. During her medical training, she and her peers took note of the faculty members who were “involved in getting the science out there,” as she puts it.

While she believed they were sincere in wanting to raise the level of care and expertise across all types of practices, she came away unimpressed by the speakers she encountered after finishing her residency. “I was happy to eat the steak because I was young and poor, but pharma companies were not selective enough in choosing their speakers. It always felt so sales-y,” Grabowsky explains.

The reality is physicians want to hear from people they respect and who they view as leaders in their own medical communities, not just the national opinion leaders

Mary Manna Anderson, Haymarket Media

She believes that is no longer the case. “[Pharma companies] lost credibility by not choosing the right physicians or KOLs. They’ve gotten better at doing that, which makes all the difference.”

That’s one of the key changes the tactic of paid speaking has seen in the past decade or so: The industry no longer calls on the same individuals time and again. There’s a new degree of rigor in choosing speakers, one that relies as much upon ferreting out emerging voices via networking as it does hasty web searches for recently published articles in a given specialty. “There are lots of people who have opinions and expertise that are important to practicing physicians,” Anderson explains. “The reality is physicians want to hear from people they respect and who they view as leaders in their own medical communities, not just the national opinion leaders. They can hear from the national people at medical congresses and other functions.”

A positive effect

In a sense, then, maybe GSK’s decision to eliminate paid speaking had a positive effect on the practice after all. The industry appears to be far more upfront and transparent about the workings of these programs than it used to be. It has expanded the topical breadth of its offerings to include more real-world evidence. The presentations are medically and legally vetted within an inch of their lives.

Or maybe it’s just that speakers and attendees alike have arrived at the conclusion that paid speaking is, as a tactic, ethical and relatively impervious to abuse — and, as such, have made peace with it. “I think people realized there’s nothing dirty about this at all,” Luby says. “It’s a physician service and a public service [for companies] to put opinion leaders who understand the science out there.”

Adds Grabowsky, “Maybe it’s that the threshold of disgust has shifted. We don’t want to go back to the boondoggle of sending doctors on a cruise to write more Lipitor. Paying them to lecture seems more academically appropriate, and it’s obviously less ostentatious.”

Fugh-Berman gets where people who are OK with paid speaking are coming from, though she fundamentally disagrees with their reasoning. “The role of the paid KOL is to never directly sell a drug — it’s to sell a disease or concept that supports marketing for a drug,” she says. “But if a drug is new or the market leader in a class [of drugs], promoting the disease is promoting the drug.”

She adds that HCPs, for all their intelligence, sometimes aren’t able to make these distinctions. “Physicians are more gullible than the average consumer. Apparently they’re a favored target for financial scams,” she says warily.

With paid speaking entrenched once again as a top-tier tactic, look for pharma to selectively increase its investments. While there’s little point in paying physicians, academics, or anyone else to speak on behalf of me-too brands, generics, or biosimilars, new drugs — or what Fugh-Berman dryly calls “drugs for invented conditions” — are ideal for the deployment of armies of A-list speakers.

“The one fear I have is that the pendulum swings back toward the cruise ships,” Grabowsky says. “But it all goes back to improving the quality of care delivered across the country. If you can get a true expert speaking about new science to educated communities of physicians who will listen, that can only be a good thing.”

From the January 01, 2019 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media