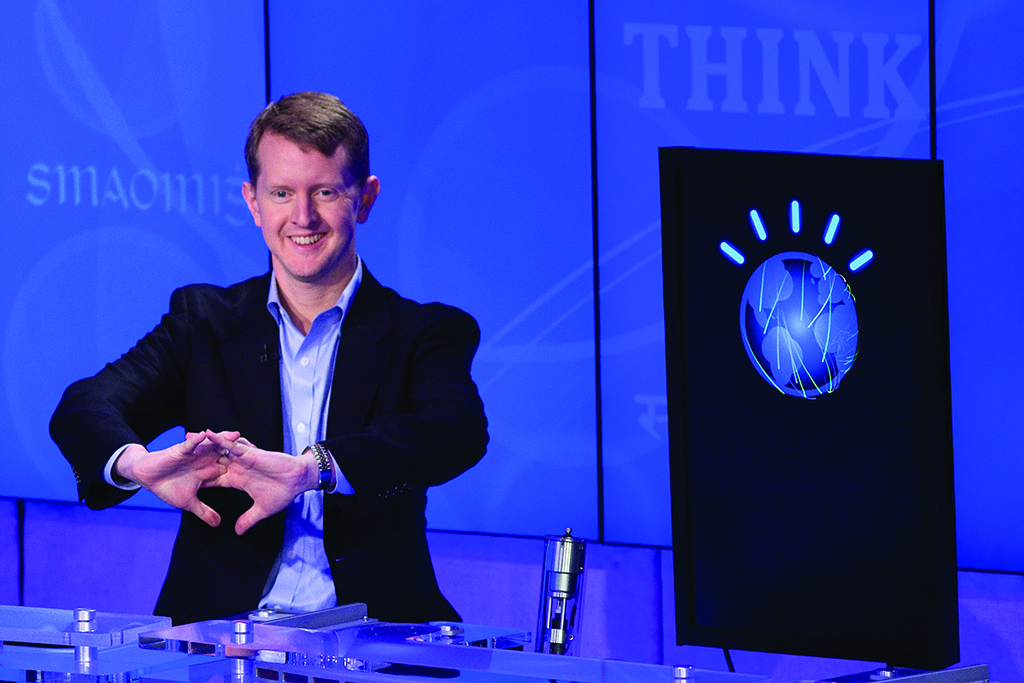

Over the course of three nights in February 2011, IBM’s Watson supercomputer stunned the world by using artificial intelligence to soundly defeat Jeopardy! champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter. It was essentially a debutante moment for the technology, with millions of viewers tuning in to watch machine trump man. Indeed, the final Watson episode was the second-most viewed program on the night it aired, behind only then-juggernaut American Idol.

With far less ado, IBM began moving Watson into healthcare that same year. The company partnered with WellPoint (now Anthem) on a project that used the computer’s understanding of language and vast data processing capabilities to suggest treatment options and diagnoses to doctors.

And then CEO Ginni Rometty famously declared that Watson Health would be the company’s “moon shot.”

From that moment onward, the hype train was cruising. By 2013, the company settled upon cancer as Watson’s first major area of focus in the healthcare arena. Seemingly overnight, it racked up an impressive slate of partners, including Memorial Sloan Kettering, MD Anderson Cancer Center and the University of North Carolina School of Medicine. The vast troves of data from these and other partner organizations would be used by Watson to improve cancer treatment, especially in helping doctors make earlier and more accurate diagnoses.

However, signs soon began to emerge that Watson’s promise may have been overblown. In 2015, just two years — and $62 million in spending — after their partnership began, MD Anderson Cancer Center ended its collaboration with IBM Watson. The project they had been laboring on, Oncology Expert Advisor, was envisioned as a source of treatment recommendations. The organizations had touted the platform’s ability to use natural language processing to read patient health records and search databases of cancer research.

By 2018, more than a dozen IBM partners and clients had stopped or scaled back their oncology projects with Watson. Earlier this year, The Wall Street Journal reported that IBM was exploring the sale of Watson Health — which, despite bringing in nearly $1 billion in revenue, was not profitable. (IBM declined to comment for this story. Meanwhile, in response to a question from MM+M about lessons learned from its partnership with Watson, a representative from MD Anderson offered the following statement: “MD Anderson constantly evaluates ways to improve cancer care and prevention and is committed to leveraging digital solutions to accelerate the translation of research into advancements for patients.”)

Watson’s failure to live up to its grand ambitions holds important lessons for healthcare marketers. After all, the story of Watson is, in many respects, a marketing story — in particular, a cautionary tale about the power of hype. Needless to say, data and marketing experts have more than a few theories about where Watson went wrong.

Many point to the sheer knottiness of healthcare data. “IBM didn’t quite understand the complexity of health records, especially the fact that the majority of them are on paper, and that they’re all recorded differently,” explains Relevate Health Group chief innovation officer Hans Kaspersetz. “They had to apply an enormous amount of human power to apply hygiene to the data, then to label it and get it into the database so that the machine learning algorithms could start to make sense out of it.”

Daniel Leszkiewicz, EVP of healthcare analytics at 81qd, agrees, adding the myriad decentralized data sources in and around healthcare layered more complexity onto Watson’s slate. “A patient could be going to Dr. Smith in one hospital system to treat his tumor for lung cancer. But that doctor, and the EHR system that Watson was looking at, didn’t know that the patient also went to the hospital two weeks ago for breathing trouble, because they might be on different data sets,” he explains.

Leszkiewicz also points out that, in using natural language processing for predictive algorithms, “the data conversion from a chart or health record into what it actually means could be very difficult,” he says. To illustrate it, he references decidedly non-medical terminology: “‘Mouse’ versus ‘mouse.’ What is the mouse that sits on my desk versus the mouse that squeaks and eats cheese?”

Or, as Kaspersetz puts it, “It’s difficult to translate text data into something that has features that can be represented mathematically, that you can then run through the algorithm, train the algorithm on those features and get good outputs.”

For instance, image data is much simpler. “A lot more of the rapid evolution of AI in healthcare has been in areas such as radiology, where you can have a bunch of scans that compare image to image,” Leszkiewicz explains. “Computers are very good at image recognition; it’s a simple ask. When we’re talking about what has succeeded in healthcare AI or prediction algorithms, that’s really one of the core elements: Ask a simple question that you can get an answer for.”

As basic as this sounds, IBM never clearly defined the questions it was trying to ask, according to Ned Russell, managing partner of the healthcare practice at MDC Partners. “The thing that Watson never did was say very clearly, ‘This is the problem that we are going to solve,’” he says.

Ultimately, Russell continues, a healthcare provider wants two main things from its technology: to deliver better patient outcomes and to limit costs. He cites the use in diabetes care of continuous glucose monitors and connected insulin pens as examples of innovations that proved their worth, and then some.

“They work and they’re very practical, and you know the problem that they’re solving. But if somebody comes in and says, ‘We want to transform the healthcare ecosystem,’ can it get any broader than that?”

The promise of technology to streamline processes and reduce the diagnostic burden on physicians, let alone help save lives, is incredibly exciting. But Watson’s inability to meet its lofty expectations strongly suggests the importance of remembering that these technologies are not held to the same rigorous standards as drugs, for example, and that messaging around their abilities and efficacy must take that fact into consideration. After all, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is still determining how best to regulate AI and machine learning in clinical settings.

“There is an enormous risk to our credibility as marketers when we drive hype cycles,” Kaspersetz says, noting current communication struggles around COVID-19 vaccinations. “As we move into the next evolution of development around artificial intelligence and machine learning, it’s critical that we demand transparency into the research that supports it, into the data sets and training corpuses that are used, and into the algorithms so that we can ensure there’s not systemic or implicit bias and that we can reproduce the outcomes in a scientific way.”

None of this, needless to say, is to label Watson as a complete write-off. “Whether they succeeded or failed is truly in the eye of the beholder,” Leszkiewicz says. “They were able to make some inroads, and the thought of applying AI to healthcare and health data has only grown tremendously.”

He cites predictive wearables such as the WHOOP wristband, which has proven able to identify COVID cases during incubation and prior to the arrival of symptoms by using a predictive algorithm that analyzes changes in respiratory rate. Then there are the Amazon Web Services tools that make it easier for providers and pharma companies to access patient data at scale. While these examples aren’t pure AI plays, Leszkiewicz believes Watson has helped spur the development of data sets that will help AI make more impactful predictions in the future.

Kaspersetz also sees a handful of big-picture positives. “They created the market conditions for a substantial amount of capital to flow in through venture capitalists, so that we could have an explosion of startups around machine learning, artificial intelligence in healthcare and healthcare marketing,”

he explains.

By way of example, he points to his own company’s LexEdge, a word-embedding analysis tool which scans huge data sets to find themes that will drive content strategy. Kaspersetz notes that its development was spurred “because of my experience with Watson at our clients’ offices and recognizing that, if we brought a tool to market and we brought this technology to our clients, they would buy it from us. Because they were buying it from Watson and IBM.”

As for what healthcare marketers should be looking for in Watson’s inevitable successors, Russell is bullish on data that can help patients act preventatively.

“The hope for connected devices, like an Apple Watch or my phone or my Halo, is that I’ll be able to know when something is going awry,” he says. “Information that will help patients proactively manage their health is what everyone should be paying attention to.”

Big data also hold big possibilities for continuous audience engagement, which demands large volumes of content. “We can use AI algorithms and machine-learning algorithms to generate fresh content. It can accelerate our ability to look at very large sets of content, particularly Reddit, Quora and Twitter, to determine the interests of our audiences,” Kaspersetz says. “You’re going to see content factories being developed within the pharmaceutical companies who are using machine learning and artificial intelligence to accelerate their content pipelines.”

In the nearly six years since MD Anderson ended its collaboration with Watson, technology and AI capabilities have advanced dramatically. It’s not a leap to suggest that, as electronic health records become more portable and biomarkers improve, the algorithms will as well. And as more physicians grow comfortable with leveraging data and AI technology, “that will create the appropriate context for a Watson-like solution to be effective in the market,” Kaspersetz says.

But if we’ve learned nothing else from Watson’s work in healthcare, it’s the importance of asking the right questions and tempering the biggest expectations. “Human involvement is what will make an analysis sing,” Leszkiewicz stresses. “A computer doesn’t always have the ability to say something is off. You can’t just let a data scientist or a coder run loose without people who really understand what the question is.”

We Bought the Hype

Back in February 2016, a handful of MM+M staffers had the opportunity to spend a day at the IBM Watson outpost in New York City. We were treated to a huge presentation of Watson’s health-adjacent capabilities and walked away dazzled … in retrospect, a bit too dazzled.

MM+M’s coverage came in the form of Watson Week, which we described as “a new online series from MM+M examining IBM’s big bet on healthcare,” Below are excerpts from the stories MM+M published as part of the series.

The editorial team’s tour of the Watson Experience Center in New York City began at the Immersion Room, a mini theater in which wraparound screens visualize the potential of Watson in healthcare. Our photographer was not permitted inside, but we saw a case study showing how Watson’s cognitive computing engine can be used by doctors to speed up medical diagnosis. IBM’s vision is for physicians to partner with Watson to “enhance human capability.”

Outside the Immersion Room, a Watson experience manager demoed Watson for Oncology, which came about four years ago through a partnership with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The tool leverages de-identified patient data and millions of journal articles and texts to display treatment options, each of which is color-coded for risk and confidence level. MSK curated the data set, and oncologists can view what studies supported the considerations.

A person can walk into a bank pretty much anywhere in the world and use his or her ATM card to draw out cash, thanks largely to an infrastructure built by IBM in the 1970s. Now, imagine the Watson cognitive computer being just as ubiquitous.

That’s IBM’s vision for its former Jeopardy! champion, and it’s quickly becoming reality. Already, there’s cognitive cooking for your kitchen and cognitive coaching for your daily run. What’s Watson’s vision for medicine?

“There’s probably a thousand different use cases, and that’s what makes my job hard because there’s no single thing we’re trying to do,” acknowledged Bill Evans, chief marketing officer for Watson Health.

We’d been struck not only by the unit’s $4 billion in acquisitions in less than 12 months, but also by the number of biopharma, medtech and pharmacy giants Watson’s been partnering with — Apple, EHR provider Epic, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Teva, Novo Nordisk and CVS, to name just a few.

Some of the use cases Evans alluded to can be seen in these partnerships. With J&J, it’s leveraging cognitive insights to develop apps for patients preparing for and recovering from knee surgery, and with Medtronic, it’s live-streaming data coming from insulin pumps to help diabetes patients predict a life-threatening event.

This month Watson announced another pharma collaboration: with Pfizer to create a remote-monitoring system to support patients with Parkinson’s disease. “If there’s a pharmaceutical company we’re not talking to at this point, I’d be surprised,” explained Evans.

MM+M asked him why IBM thinks it can succeed in harnessing big data for things like the Triple Aim where other data and analytics providers have not.

“We’re not a Johnny-come-lately company,” he replied. “This is a company that’s a hundred and some years old; it’s 350,000 people worldwide. It’s got a legacy of being invaluable to the businesses that it serves.”

But IBM has been a B2B healthcare company all these years. For instance, its life sciences division wrote the first pediatric medical record in the late 1960s and has worked with health systems for decades.

With the launch of Watson Health, the company is trying to be more front-and-center in the eyes of the consumer, and to use cognitive insights to improve lives and reduce waste.

Yet here we are, a year after Watson Health’s formal debut, and the organization has experienced a growth spurt of a magnitude that not even its most pie-eyed optimists could have anticipated. Following the most recent of Watson Health’s purchases — Truven Health Analytics, which brought with it yet another treasure trove of data — headcount has surged to around 5,500 people. Contrast that with the situation a year or so ago, when Watson Health VP of partnerships and solutions Kathy McGroddy-Goetz routinely made big decisions in tandem with a few members of IBM’s legal and tech teams. “And then we woke up one morning with all these new processes,” she recalled with a laugh.

McGroddy-Goetz adds that her perspective has similarly evolved. “A year ago, I was probably appreciating what we’re doing more from the perspective of a technologist,” she continued. “But as I spent more time with our colleagues at Medtronic and with IBM people who have a family member with diabetes, that’s when I saw how impactful everything we do could be.”

McGroddy-Goetz points to an instance that crystallized this impact in her mind. “We met a child with diabetes who had a therapy dog that woke his parents in the middle of the night when he was going hypo[glycemic]. It was harrowing,” she recalled. “As our relationship with Medtronic developed, it was almost startling. ‘My God, the technology we’re working on could give [diabetic patients] three or four hours of advance notice.’ Three or four hours in a situation where every minute can be crucial — that’s a big jump.”

(published April 14, 2016)

From the September 01, 2021 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media