The struggle is real. Health data is governed by laws nearly 25 years old, and as more types of health data are created, from fitness to biometric to genetic data, Washington can’t keep up.

Laws to manage these new types of data have fizzled. The bills exist, but most never even make it to committee consideration, the very first step to becoming law. The current authority in health data privacy is HIPAA, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which became law in 1996.

Meanwhile, the regulation of digital health data is being taken over by wide-ranging online privacy laws such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA).

However, these privacy regulations also aren’t specifically meant for digital health data. So marketers working with online health data have cobbled together methods to manage it that take into account all of these regulations: HIPAA, GDPR, CCPA and other privacy laws.

Some experts say HIPAA is becoming less relevant as health data is changing and becoming more digital.

Two health privacy researchers, Lisa Bari and Daniel O’Neill, wrote in the journal Health Affairs in December that the limits of HIPAA have been reached and unclear regulations could have consequences for the public.

“Without clear guardrails, public trust may crumble in the face of repeated scandals and so undermine the potential for digital health to facilitate an era of more accessible, coordinated and personalized care,” the researchers write.

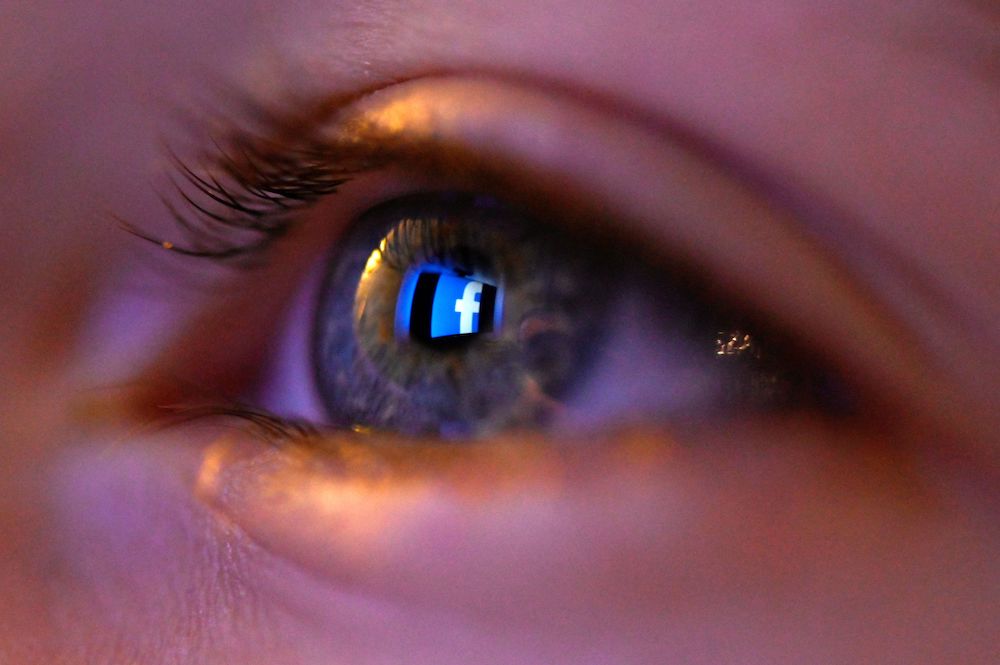

In fact, an example of how private health information is migrating online comes from Facebook. The social network launched a “preventive health tool” last fall, where users can input if they’ve visited their primary care doctor or gotten certain annual screenings. But it’s unclear who will be able to see the data.

Facebook said the health data would not be shared with other users, advertisers or health insurers, but did acknowledge that a small group of internal employees will be able to see it.

Health data is governed by laws nearly 25 years old, and as more types of health data are created, from fitness to biometric to genetic data, Washington can’t keep up.

But Facebook doesn’t necessarily fall under HIPAA, or its 2009 amended version, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act. Those two laws designate “protected health information” only as information created by certain entities such as provider organizations, insurers or clearinghouses.

Yet, Facebook and hundreds of apps, fitness wearables and genetic testing companies are being given this extremely personal health data.

Other privacy laws such as GDPR in Europe have put more stringent regulations on health data, compared to other types of data. The law prohibits the processing of health data, which includes all forms of managing, collecting or storing data. There are few exceptions to that rule, such as the individual giving explicit consent to process health data or if the data is of substantial public interest.

CCPA also fills in some of those gaps, although it only applies to California residents. That law applies its data protection and ownership standards to all for-profit organizations in California that have more than $25 million in revenue or data from 50,000 individuals.

That fills in some of the Facebook-like gaps in digital health data privacy. Companies that have health data, but don’t necessarily fall under HIPAA, may fit within CCPA, providing extra protection.

For professionals who work with health data, keeping up with these regulations, standards and potential regulations is paramount.

The worst-case scenario for these data wranglers would be a patchwork of data privacy laws such as CCPA, instead of a single national law.

“I do see an uptick in various states trying to do something like California did,” says David Windhausen, EVP of development services at Intouch Group and president of Intouch B2D. “You have the potential of having 50 different regulations and that would really not be a good thing. It would be better if we could have some standardization there.”

Windhausen says there have been “hints” that other states are considering their own data privacy laws like California.

Last summer, the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), advised policymakers to give more types of health data

HIPAA-like protections.

The committee’s report, released in June 2019, said, “The range of use cases of health information beyond HIPAA is vast.”

“If [organizations] are outside of HIPAA, they have a variety of limited obligations to protect the privacy of the health information subjects. They are not subject to the uniformity that patients now expect from the HIPAA rules. Today, safeguards for individually identifiable health information too often are weak or nonexistent,” it continued.

The committee recommended the government and the private sector work together to create new privacy laws and best practices to protect the health data that falls outside of HIPAA.

Six months later, in December 2019, the committee sent a letter to HHS Secretary Alex Azar. It urged him to enact expanded health data privacy protections, saying the industry had asked the committee to “do something and do something now.”

There are several proposed bills to change health data protections. But none have gone further than being introduced before the chamber. One of them is based on the committee’s report.

Shortly after the report was released, Sens. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) introduced a bill to fill the gaps in HIPAA.

That bill would expand protections to genetic, biometric and personal health data, and establish a task force to monitor health data called the National Task Force on Health Data Protection.

Another bill, the Stop Marketing And Revealing The Wearables And Trackers Consumer Health (SMARTWATCH) Data Act, focuses specifically on wearable data.

It seeks to prohibit the use and sale of data from wearables without informed consent and classifies that consumer health data, including health status, personal biometric information or personal kinesthetic information, as “protected health information.”

These proposals are still up in the air, so data experts are doing business as usual with their data.

Windhausen and Michael Blake, SVP of development and quality services at Intouch, say keeping data organized is the top priority.

“We keep a catalog of all the data that we store or process and we classify that data based on its use,” Blake explains. “Maybe it’s public data or more confidential data. Does it have identifiable information in it or is it concerned with protected health information? The classification is a big deal. Then we define, based on that classification, how we address the data across several touchpoints, like moving, storage, transmission, destruction and certainly processing.”

Blake says that HIPAA and other data privacy laws may be broad, but they still provide the fundamentals for managing data.

“The regulation itself raises that flag that if we’re going to work with [protected health information], here are the things that need to be in place,” Blake says. “Technology will evolve how we access data and how we get it may evolve over time, but the fundamentals are there. It’s the protection of privacy and confidentiality of the data.”

From the February 01, 2020 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media