Last December, healthcare wonks in Washington anticipated a relatively slow 2020 on the health policy front. Presidential election years tend to induce political paralysis, which led most experts to believe that any changes would be incremental in nature.

Maybe there would be some movement on drug-pricing reform, they speculated. Data privacy seemed ripe for bipartisan agreement, especially with the California Consumer Privacy Act roiling organizations already fed up with navigating the patchwork of state laws. Modification of the Affordable Care Act remained within the realm of possibility, though most experts believed that the courts would have the ultimate say on its future.

And then COVID-19 hit, and that was that.

Not only did it derail other significant Congressional action in the healthcare realm, but it closed the door on the executive orders that might have moved the goalposts — again — around drug pricing or the disclosure of pricing information in DTC ads. With good reason, health policy became all COVID, all the time.

“COVID completely derailed the agenda,” ZS managing principal and global pharmaceuticals practice lead Pratap Khedkar says flatly. Jon Bigelow, executive director of the Coalition for Healthcare Communication, agrees: “COVID interrupted every timeline and priority in Washington.”

So while policy people energized by the promise of a new political configuration haven’t been shy about rolling out their wish lists (hello, pricing) and ranking their worst-case scenarios (yet another tango with the possibility of eliminating or limiting the tax deductibility of marketing expenses), they have calibrated their expectations around the reality of COVID-19. If the Biden administration moves aggressively to combat the virus, there could be action on a number of fronts. If not, from a health-policy perspective 2021 will essentially be 2020: The Sequel.

If the pandemic continues for another year, it scrambles any hope of doing anything on prescription drug.

Terry Haines, Pangaea Policy

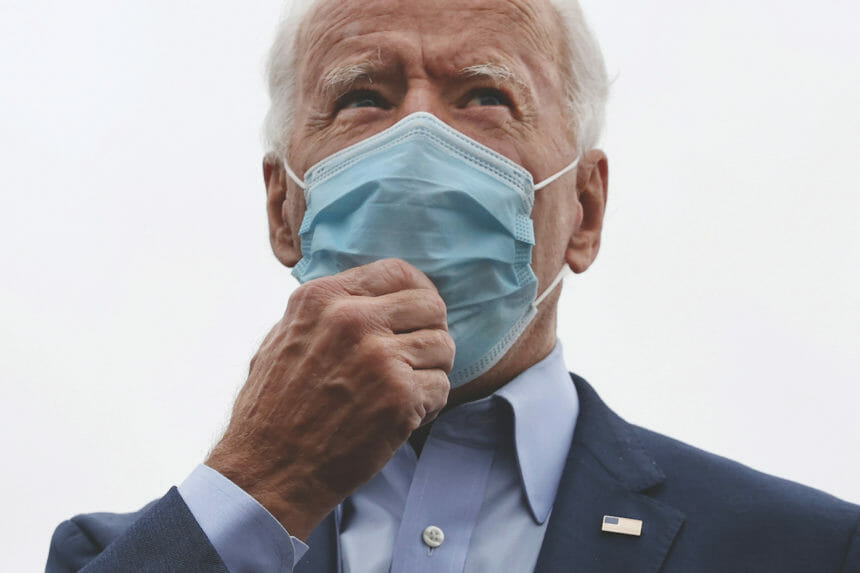

Which isn’t to minimize the stakes, most importantly in terms of people’s lives, but also in the context of President-elect Joe Biden’s ability to govern successfully.

“He has the opportunity to make the kinds of decisions with COVID that will either bring people together or drive people apart,” says Terry Haines, founder of healthcare policy consultancy Pangaea Policy. “Either he’s going to do something that’s sensitive to the virus, with the economic part and everything else, or he’s not. If he decides to do something that comes down hard on one side or the other, he’s going to lose a lot of people who’d otherwise be willing to support him.”

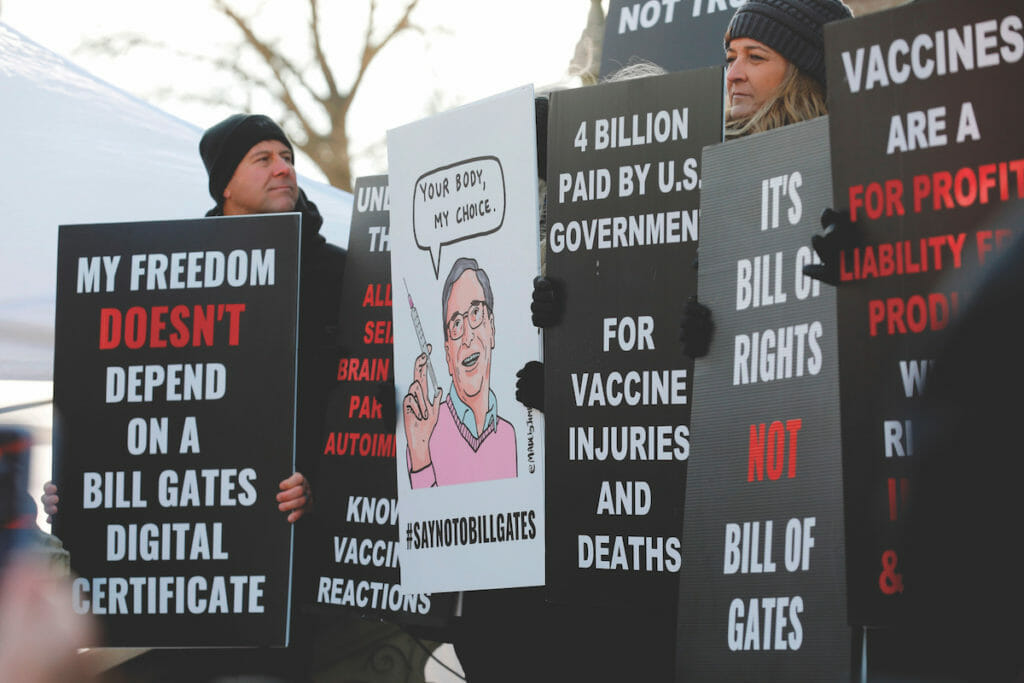

Then there’s the behavioral-change component that accompanies it. While vaccines are (rightfully) receiving much of the attention, the pandemic doesn’t come to a screeching halt when they’re deployed.

“The ‘How do I change the behavior of 300 million people, some fraction of whom might be skeptical, to adopt this thing?’ is a management problem …. This is not a problem of clinical medicine alone,” Khedkar notes.

Haines believes that Biden’s COVID response will color, even define, the rest of his presidency. His concern? That a second stimulus package will be perceived as overly beneficial to Democrat-run cities and states, an ask from House Democrats that tanked recent stimulus talks.

“I’m not faulting [Speaker Nancy Pelosi] for that, but the idea that in this stimulus you were going to do things not related to COVID — that’s why Republicans wouldn’t move,” Haines explains. “Substantively, they thought it was outside the bounds of a COVID bill.”

This, he suggests, could prove dangerous. By way of comparison, Haines points to the stimulus package signed into law in February 2009 by a newly inaugurated Barack Obama, which he believes was largely written by Senate Leader Harry Reid and House Leader Pelosi.

“When the initial decisions of a presidency are partisan, things don’t go well for a while,” Haines adds. “Others have had better luck when the mix was more bipartisan.”

While you’ll never get anyone to say it on the record, pharma companies were alternately confused and appalled by the Trump administration’s approach to the issues confronting the industry. Did they enjoy their tax breaks? Almost certainly. But with the favorable financial climate came a degree of unpredictability that was anathema to a majority of companies and their people.

By way of example, Khedkar points to the push by the Department of Health and Human Services to address high drug prices. He believes the agency and its leader, former Eli Lilly U.S. chief Alex Azar, were consistent in intent but all over the place in execution. The executive branch might have had a little something to do with this.

“[HHS] wanted rebate reform and something to change on pricing in order to make sure patient affordability was addressed, which are reasonable things to push for,” he explains. “Then suddenly the push was for legislation — oops, that’s not happening because the House went the other way. OK, now there’s an executive order — wait, no progress there — and now there’s another set of executive orders.”

The whiplash was not appreciated, “It was, ‘Let’s try this, let’s try that,’” Khedkar continues. “They tried multiple things — sometimes they could have gone further, but they didn’t. Once you do that two or three times, people not only get confused, they don’t know if you’re being serious.”

Pharma companies weren’t entirely silent about their dissatisfaction with the helter-skelter approach. As Bigelow notes, during typical election cycles pharma leaders and related political action committees tend to lavish more money on Republican candidates than Democratic ones. During 2020, the opposite was the case.

It’s a safe bet that pharma is content with the election results that, as of late November, seemed most likely: a centrist Democrat in the White House and a Republican-controlled Senate set to counter the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives.

“For the pharma industry, the outcome is probably as good as it could have wanted,” Bigelow says. “Because Republicans will probably control the Senate, Biden will be limited in the type of measures he can push through Congress. That reduces the risk to pharma quite a bit.”

So say goodbye to some of the progressive policy goals pharma disdains — especially potentially draconian action on drug pricing — and hello to the stability and moderation it craves. President-elect Biden is already all-in on a comprehensive, science-led approach to battling COVID-19; also, he has more knowledge of the intricacies of the healthcare ecosystem than most incoming leaders owing to his work on the Cancer Moonshot initiative. It stands to reason, then, that any Biden administration policy pivots around pricing or ACA reform won’t be made rashly (nor, for that matter, will they be communicated via tweet).

One senses at least some degree of across-the-aisle interest around drug pricing reform, which Haines believes is an issue ripe for bipartisan agreement. He points to the ubiquity of pricing pitches in election-year ads as a sign that politicians view it as a needle-mover.

“You saw politicians from both parties in a lot of different states talk about it,” Haines explains. “In Virginia, for example, there wasn’t a top-of-the-ticket race that was close, but you had [Democratic Senator] Mark Warner talking in his ads about the things he was doing around prescription drugs and pricing. That’s how much it resonated: Even in a year there wasn’t a whole lot happening, Warner felt compelled to talk about it.”

Democrats were equally eager to talk about the politicization of the Food and Drug Administration. Despite the threat they claimed was posed by the influx of political appointees without meaningful scientific backgrounds, most policy experts believed the agency was on the way to righting its ship as of mid-November.

While current FDA head Dr. Stephen Hahn hasn’t received the high marks and accolades of his predecessor Dr. Scott Gottlieb — who, during his two years in the role, was hailed as perhaps the most forward-minded agency leader appointed by the Trump Administration — his tenure wasn’t anywhere near the disappointment some pundits expected, given his prior lack of health policy experience.

At the same time, it’s a near-certainty that Biden will move to install an individual with significant public-health experience atop the FDA. His shortlist is said to include Dr. Joshua Sharfstein (formerly a principal deputy commissioner at the agency) and Dr. Luciana Borio (an infectious disease physician who previously served as the agency’s acting chief scientist and assistant commissioner for counterterrorism policy).

“To me, it’s less about senior leadership and more about letting the FDA be run the way it was supposed to be run,” Khedkar says. “It’s about removing the political constraints and other interjections …. It wasn’t a systemic problem.”

Bigelow, on the other hand, believes the appointment is a crucial one, coming as it will at a time when confidence in the FDA remains shaky. “Restoring credibility is the first goal, for several audiences,” he says. “One is the public, because there are concerns around the safety of COVID-19 vaccines. One is the internal staff, which has been demoralized. And another is the pharma industry, because it wants someone who’s a responsible person who really understands the drug-approval process.”

Ultimately, healthcare policy in 2021 is going to hinge on shrinking the threat posed by COVID-19 to every aspect of life in the U.S. If a more deliberate federal push on the public-health front diminishes it sooner rather than later, there’s a good chance non-COVID-related policy goals can be achieved. But if the pandemic lingers into the second half of the year, forget about big action on the pricing front — and given that 2022 is a midterm election year, forget about most anything else of substance.

“If the pandemic continues for another year, it scrambles any hope of doing anything on prescription drugs and pricing,” Haines says. “On the other hand, you can do some ACA tweaks and Republicans would certainly join with Democrats to make sure [the protection of] pre-

existing conditions continues. ‘Pre-existing conditions’ — that’s the new bogeyman, right? It’s replaced Social Security as the third rail.”

Still, the imminent changing of the political guard has given rise to something akin to optimism among policy watchers. Khedkar isn’t hopeful about a quick end to the pandemic — “even if we have the right medications, rolling them out and getting 300 million people into herd immunity is a 12- to 18-month exercise” — but he does anticipate “more clarity and direction from the top, which absolutely helps.”

As for Bigelow, he’s perhaps the most bullish on the possibility that Biden will prioritize bolstering the ACA, whether by increasing the amount of funds spent marketing its plans, eliminating so-called “skinny” plans or by other means. He also expects some movement on data privacy legislation, assuming that any federal bill preempts the current hodgepodge of state legislation.

Overall, Bigelow echoes Khedkar’s hopefulness around the country’s new leadership. “I am optimistic in the sense that I believe the new administration will dot the i’s and cross the t’s. When they have a policy proposal, they will have thought it out and will communicate it better. There will be fewer zigs and zags.”

From the December 01, 2020 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media