The Medical Advertising Hall of Fame’s three new members have each made lasting contributions. Kevin McCaffrey and Larry Dobrow take a look at their achievements and find that, years later, digital media, healthcare advertising and promotional analysis still bear their imprint

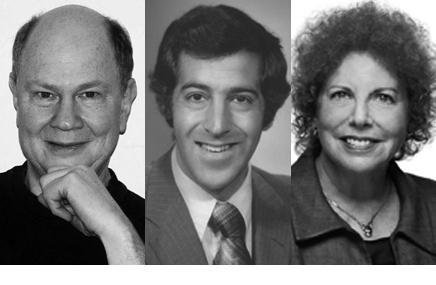

Peter Frishauf

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS

1960s While a student at NYU, switched major to journalism, becoming editor of Washington Square Journal1970s Started F&F Publications, bought Hospital Physician from Medical Economics and launched Physician Assistant. F&F was sold in 1977 and Frishauf served as editorial director for new owners, PW Communications1980s Raised venture capital through Alan Patricof Associates to start SCP Communications, a paper-free electronic community1990s Left SCP and formed Medscape, amidst growing popularity of the internet

1998-1999 Stepped down as CEO to assume role of chairman of the executive committee; Medscape completed its IPO and reached 600,000 registrants

2002 Medscape was sold to WebMD, ending Frishauf’s formal relationship with the company

Today the physician’s media mix teems with health and medical information sites, social networks and other resources. Not so the World Wide Web of the mid-1990s. Medscape set the industry standard with some of the first medical, peer-reviewed and CME content. It featured targeted advertising before most pharma companies even had websites. And nearly two decades after its launch, Medscape continues to be a major online clinical destination. Much of the credit goes to co-founder Peter Frishauf.

When were the seeds for these achievements planted? A turning point was Frishauf’s decision to switch his major to journalism while at NYU, during a time when the Vietnam War was top of mind for the country, and especially its students. Frishauf, much like his peers, wanted his voice to be heard and sought a larger audience.

“I started out as pre-med,” he says, “but I was bored with basic science studies during this era of great social upheaval. I was much more interested in addressing broader issues.”

In 1968, Frishauf started out as a copy boy (“before there were copygirls,” he quips) at the New York Daily News. “I was the low person on the staff, but you got to see every piece of the operation. They were using very slow technology, but still worked quickly with an efficient and engineered workflow. I kept having this notion that you could replace copy boys with computers. ”

Frishauf is the son of an electrical engineer and a physician, and the apple didn’t fall far from the tree as far as where Peter ended up focusing his professional endeavors. In 1981, 14 or so years before the internet began to gain traction, Frishauf started a paper-less electronic company and community called SCP Communications, where he set about re-engineering the workflow processes for peer-reviewed scientific publishing.

Frishauf channeled the work philosophy he witnessed at the Daily News, applying the process to magazines. “I often wondered why magazine publishing is so embarrassingly slow when science is so important,” he says. “The so-called peer-reviewed journals would say, ‘That’s because we want to get it right,’ but articles would take somewhere between an hour-and-a-half to three years to be published. There had to be a better way to do things.”

Continues Frishauf, “I thought computers would really be a great tool to create the kind of productivity that I saw in newspapers, but with a smaller startup kind of a staff.”

This insight was the foundation for the microcomputer Peter would re-engineer to form a multi-user and multi-task system. “We created a system which pretty much eliminated typewriters from the equation,” he says. “It was very much like Google Docs. Memory and disc space were precious at the time, so the technology forced us to share.”

As the web began to take off, the price of sharing information fell—allowing the birth of Medscape to take place in three short months in 1995. “When the internet came along, the cost of sharing information just dropped like a rock,” notes Frishauf. “The key was: could you trust the information? We were uniquely qualified because we had a lot of experience creating trustworthy information and as an electronic community.” Within one year, they would see over 40,000 registrants and 700 daily visitors.

In 1999, Medscape had over 600,000 registrants and hired Dow Jones veteran Paul Shiels as CEO. Frishauf served as chairman and advisor. That year, Medscape completed a successful IPO. Frishauf served on the board of directors until 2002 when Medscape was sold to WebMD. His formal relationship with the company would end one year after its acquisition, but not his influence: Frishauf remains a vital force as a leading digital guru. —Kevin McCaffrey

David Labson

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS

1960s Received BS degree in pharmacy from Medical College of Virginia (now Virginia Commonwealth University) and, with Sloan MBA in hand, signed on for Merck’s two-year fast-track manager program

1970s Left Roerig division of Pfizer to found Health Industries Research, a pharma marketing consultancy; introduced Exposure Value Audit, HIR’s first research product, then FOCUS syndicated readership study, a product designed to assess the reach, frequency and impact of medical advertising

1980s Sold HIR to VNU, which merges it with PERQ Research; published first issue of Contemporary Internal Medicine, a monthly journal for internists

Had David Labson never existed, or had he wrapped his agile mind around a field other than medical marketing, the business would eventually have warmed to the use of data. Sooner or later, it would have embraced the practical metrics that Labson embedded into his analysis tools. At some point, it would have found a way to steer needed information to medical marketing agencies, which hadn’t yet been brought into the research loop.

But it would have taken far longer than it did on Labson’s watch. More than two decades after his death, the syndicated readership study he developed, FOCUS, is still among the industry’s most trusted methodologies (albeit under a different name). And that’s before you take into account the wisdom he imparted as a consultant.

“When people bought the research, what they were really buying was David Labson’s consulting services,” says Mark Branca, director, IMNG Society Partners, who worked at Labson’s firm Health Industries Research. “He did it all with such ease.”

Labson grew up in Roanoke, Virginia, and entered the Medical College of Virginia. But his plans to become a doctor changed after one biology class. “He did his first dissection and just couldn’t stand it,” recalls his wife, Lucy. To assuage his parents, he pursued a pharmacy degree, but a professor steered him toward business school.

Two years later, Labson graduated from MIT’s Sloan School of Management and took his first industry job: in an immersive management training program at Merck, known internally as “the Golden Boy program.” That led to a post at Geigy, where he started as a market research analyst and, before long, headed the department. Soon, however, a sort of professional restlessness set in. He switched gears, joining Pfizer’s Roerig division as a product manager and ascended to the post of co-director of marketing.

The wide range of experience early in Labson’s career laid the foundation for what would come next. “He could talk about every side of the business. He could put himself in the shoes of just about any type of client,” Branca says. Those early jobs fueled his drive to ask tougher questions—prompting him to venture out on his own.

“He had this entrepreneurial, independent streak,” Lucy recalls. “Every other year, something would come up—‘Wouldn’t this be a great thing to do?’ Eventually, I said, ‘Go ahead and see what happens.’ The worst thing would have been to never give it a shot.”

Thus was Health Industries Research born. Within four years, Labson had devised his game-changing Exposure Value Audit and FOCUS measurement products, which measured readership, ad exposure and qualitative aspects of media. To hear another healthcare media godfather tell it, Labson refused to accept the status quo.

“He felt that, in addition to the data on readership and ad page exposure, it was important to know the nature of the environment that publications provided for an ad message,” says David Gideon, founder and CEO of PERQ, which ultimately merged with HIR. Gideon also praises Labson for his inclusive bent: “At a time when virtually all syndicated research was only sold to manufacturers, David made the decision to make his available to ad agencies.”

Labson sold HIR to publishing/research conglomerate VNU and, when he died in November 1990 at the age of 50, had just founded a publishing company, Aegean Communications. However great his professional achievements might have been, though, his peers remember him as an even better person.

Branca says he “can’t begin to count” the number of personal and professional generosities he witnessed during his time at HIR—Labson picked up the tab for his MBA—and says that the happiest he ever saw Labson was on the day he learned his son had been admitted to Harvard. Lucy, on the other hand, quips that “the man was always happiest with a clipboard or a ball in his hands”—which explains his devotion to coaching a basketball travel team for seventh graders long after his son had entered high school.

But Lucy says it mostly speaks to her late husband’s generosity of spirit, as did his involvement at the local synagogue (David was its president when he died). “He was very present, both for me and for [their son] Mike. We traveled extensively, to Egypt and Israel and Greece and China, and spent so much time together,” she says. “But there was never a time when someone needed a good friend that he wasn’t there for him. He never shied away from hard situations. He was really a fearless person.” —Larry Dobrow

Dorothy Philips, PhD

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS

1960s Received her MBA from NYU and won a Ford Foundation grant for her PhD on the study of promotional tools in healthcare communications

1970s Joined J. Walter Thompson as a consultant, and rose through the ranks to SVP, marketing services, where she grew a business in coordinating healthcare symposia

1980s Left JWT for Barnum Communications, starting in account services and becoming president four years later

1990s-2000s Started her own agency, Philips Healthcare Communications, where she served as president until 2012 and did some of the first promotional work for vaccines

Dorothy Philips, one of the few non-Mad Men to break into healthcare advertising during its golden age, forged a path to success on which countless women have followed. Upon completing her undergraduate degree, Philips saw few opportunities. One area she enjoyed was market research, where she landed her first job. “It was creative and we were doing things that nobody else had been doing, like focus groups and going to stores,” she says. “I really enjoyed the contact with consumers.” Soon after, Philips would also marry and, this being 30 years before the Family Medical Leave Act, was out of a job as well. “In those days, they told me, after they found out I was pregnant, ‘Thank you very much,’ and to stay home and take care of my baby.”

Philips wasn’t content to remain a stay-at-home mom. She completed her MBA at NYU and, after applying for a research assistantship and receiving the position, found a new home in academia. This, too, suited her talents. “I went to work with one of my professors, but while doing that, he had a Ford Foundation grant which would pay for my PhD,” she says. “It was for business, marketing and economics, so I thought if I was going to have difficulty finding a job, maybe I should stay in school—I was good at it!”

Philips received that grant and began to work on her doctorate. But her plan to lay low in academia didn’t last long. A short time later, a client of her husband’s changed everything. “My husband was doing work for a client from a pharma company. The client knew I had a research background, and she asked me if I would do a project for Pfizer,” she explains. “The project involved taking a look at promotional tools in the pharmaceutical industry, so I did. And what I found was that there was little information to be found anywhere.”

Inspired by this knowledge gap, Philips had found a topic for her dissertation: a study of promotional trends in what was then called the ethical pharmaceutical industry. “In the process of doing this, I went across the country and interviewed the marketing VPs of 28 companies.” Through that process, she met Jim Barnum, who had started a healthcare unit for consumer ad agency J. Walter Thompson. He would have a great impact on the rest of her career.

“[Jim] was a very imaginative person,” she recalls, “and he was ahead of the times. In 1971, he was thinking of starting a subsidiary agency that would provide medical education for doctors via TV. So what I was doing was showing that this kind of idea had some legs—he then went through what I was doing, and asked me to work for him. So I did.”

Over the next eight years, Philips’ career in advertising would flourish, but Jim Barnum left J. Walter Thompson, later relaunched as JWT, to start his own agency. She would eventually assume the role of SVP, marketing services for Deltakos, the official medical advertising branch of JWT. But even a decade after being told to leave her job when becoming pregnant, past notions remained: “I remember people saying things like, ‘There were no women sales reps in the pharmaceutical business, because the bag was too heavy to carry.’ People really said things like that.”

The bag would not prove too heavy for Philips, who in 1979 was offered an account services position from Jim Barnum at his own agency, Barnum Communications. By 1983 she would run the shop as president, helping introduce new techniques and pioneering the use of PR to drive adoption while working on products as revolutionary as the first test to measure blood glucose.

In 1990, Philips started her own agency, Philips Healthcare Communications, which still exists and is known for its novel work in vaccines. In 2012 Philips announced her retirement from formal agency work. She now focuses on work for philanthropic organizations like the National Executive Service Corps, which provides consulting services for non-profits. She is also an active board member for Lighthouse International, an organization serving the needs of people who are blind or have low vision. —KM

From the February 01, 2013 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media