When intense abdominal pain slammed tech exec Ali Diab in 2013, he needed emergency surgery to untangle his suddenly twisted intestines. Predictably, a mountain of medical bills followed him home. Given that he had good coverage and the support that comes with being part of a family of doctors, not to mention years of experience purchasing health plans for businesses and degrees from Stanford and Oxford, “ ‘How hard could it be?’ ” he recalls.

Pretty hard, it turns out. In the months that followed, Diab was treated to the insurance-company runaround so familiar to millions of regular Joes. “The insurance company refused to pay claims, blaming it on physician error,” he says. “They insisted I was calling the wrong number, even though it was listed on my insurance card. Here I was, at my most vulnerable, and instead of helping, the service was insultingly bad. It was like my insurance company was a black box.” The experience was so antagonistic that it inspired Diab to start Collective Health, a San Mateo, CA–based business that provides self-insurance options for companies.

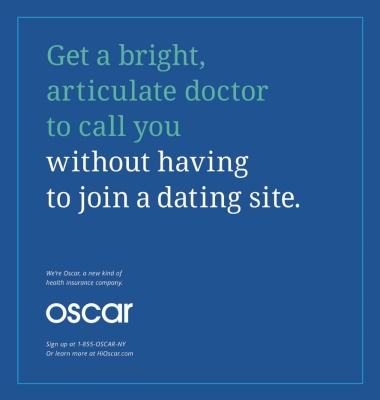

Collective Health is one of a fast-growing number of organizations out to melt the icy hostility that often characterizes relations between insurance providers and consumers. Others include Oscar, the small insurer that is wooing Gen-Y consumers with the likes of snarky ads, free wearable fitness trackers and Amazon gift cards in return for walking more, and Wellthie, which helps insurers craft more consumer-friendly messages. Their impact is already being felt: A report from PwC finds that these upstarts—similar to ones that have upended retail, banking and travel—pose an “imminent risk” to $64 billion of the $2.8-trillion healthcare market.

What they’re doing right (or wrong, depending on where one stands): They’re fostering more health-literate customers by becoming more customer-literate themselves, a task made more challenging by the fast-changing landscape of the Affordable Care Act and consumers’ own increasing expectations within the digital and service realms.

While insurers have made commendable efforts to become more customer-centric, the industry still has a long way to go. The University of Michigan’s American Customer Satisfaction Index says that of the 48 industries it tracks, the only categories consumers hate worse than health insurers are ISP providers, cable companies and airlines. (When a business finds itself in the company of Comcast and United Airlines, it’s time to call in the cavalry.) Put another way, customers would rather apply for a loan, argue with their cell phone carriers or visit the post office or—gasp!—the DMV than endure a runround with their insurer’s “customer care” agents.

But as more organizations try to find a path to glasnost, it’s becoming clearer that the road from customer contempt to delight is hard to navigate. “Let’s face it,” says Deanne Kasim, director of research for IDC. “This is a huge paradigm shift for legacy companies.”

Getting past the apps

Upstarts and major players alike are trying to figure out new mobile strategies, improve access to doctors via telemedicine, increase wellness efforts and speed and clarify all things reimbursement-related. They want to move beyond confusing communication (why issue look-alike nonbilling statements reading, “This is not a bill”?) and get to a place where they “figure out how to become a partner in a family’s healthcare,” says Sally Poblete, founder and CEO of Wellthie, a company that works with such clients as Geisinger and Kaiser Permanente. “Historically, the industry has not experienced a high level of trust.”

But as the ACA has leveled the playing field and created more consumer choice, insurers are changing their strategies and tactics. They’re repositioning themselves as “being in the customer-service business,” Poblete continues. “It’s a big adjustment. We help them by looking at the technology, making it friendlier and simpler.”

And it’s not just about handier apps and more civil-tongued customer-service reps, either. Much of the emphasis is on transparency—in terms of coverage, claims processing and price. After all, if Flo, the friendly rep from Progressive’s beloved ad campaign, can promise viewers an apples-to-apples auto-insurance comparison, you can’t blame consumers for expecting at least a little of the same from the health-insurance biz.

“Consumers want benefit transparency,” Poblete says. “They want to know, ‘What’s in my plan and how do I make the most of it?’ ”

The PwC report finds that in the last three years, venture capital firms have poured $400 million into start-ups targeting price transparency, with players including both new and traditional companies, among them Castlight Health, Truven Health Analytics, Healthcare Bluebook, HealthSparq, Aetna, Cigna and WellPoint. Transparency has special urgency for younger consumers, who are vital to the success of healthcare reform.

Smaller providers like Oscar, which now serves some 17,000 consumers in the New York/New Jersey area, have done well by “targeting a very specific population among younger consumers and those with certain healthcare conditions,” Kasim says. “Even if this model isn’t easily replicated, more stakeholders in the industry should pay attention to it. Healthcare has a lot to learn from industries like retail and banking. They understand that for younger people, ‘I want what I want when I want it’ is key.”

It isn’t that the large companies haven’t been trying. “We’re now seeing the large health plans entering the second and even third generation of their apps,” Kasim notes. “There’s been a huge learning curve and there hasn’t been much customer engagement. They’re not nearly as sexy as retail apps.”

Some established insurance firms are rethinking their strategy altogether. Kasim points out that after several iterations, Aetna recently announced that it would pull the plug on its ambitious CarePass health-data platform, simply because it never caught fire with users. (Some venture types, it should be noted, worry that Aetna’s experience may be a bad omen for Apple’s much-hyped HealthKit.)

“There is this growing sense that you can’t just build something and expect consumers to come,” she says. Insurers are “realizing that it’s like retail: It has to be sticky, it has to be engaging.”

Building literacy from the ground up

If technology is the hard part, industry observers are quick to point out that insurers don’t do all that well on the basic components of communication. “Insurance companies need to have clear communications and be a trusted source of information,” says Marc Sirockman, EVP at patient-education agency Artcraft Health. “Things should be written at a sixth-grade reading level, in multiple languages, in easy-to-read fonts.”

Too often, insurance companies mail out communications that treat people like first-time customers. “Your insurance company knows what diseases you have,” Sirockman adds. “Why can’t they send you a weekly newsletter about diabetes, for example, or depression? They could put together great packages for the entire family and show ways they are advocating for your health.”

Granted, there are challenges to any such approach, especially given the massive education effort that people require to become smarter shoppers on healthcare exchanges. Diab compares it to walking into a supermarket: “I can show you 10 shelves of different types of ketchup, but if you’ve never had ketchup before, you can’t decipher it. We hear from HR managers that employees still get very confused.”

Still, Diab believes the tide can turn, albeit at a far-slower pace than modern-day empowered consumers have come to expect. “It’s not rocket science. You put the customer experience first and you’ll get loyalty above and beyond what you expect.” To do so, Kasim says, more insurers may choose to hire a chief engagement officer, a C-level exec who typically has a strong marketing and UX background. “These people are finally making sense of the process.”

A siren call for outsiders

While Poblete describes health insurance as “a mature industry, large, complex and slow to change,” there are signs that even the most entrenched organizations are becoming more open-minded about how to solve problems. Case in point? The US Department of Veterans Affairs, mired in a host of complex (and embarrassing) problems, tapped Bob McDonald—a former CEO of Procter & Gamble, as opposed to someone from within healthcare—as its new leader.

Diab, for one, would likely hail that appointment. “Only outsiders will be able to transform the insurance/consumer relationship, like Apple did with phones and Tesla did with cars,” he says. “When you’ve been an incumbent for a long time, you adopt that mind-set. There is a point when people are too realistic. It requires an outsider with a certain amount of naiveté to say, ‘We gotta change this. Someone needs to shake things up.’ ”

“In order for innovation to come about, you need a mixture of ideas, but also people who understand consumers,” Poblete states. “We speak a lot about tech and, of course, we are a tech company that uses data to drive innovation. But what matters is the combination of high tech and high touch. That’s what makes healthcare unique.”

From the January 01, 2015 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media