A slew of studies have tracked the industry’s unexpected reputational gains since the start of the COVID-19 crisis. Experts share how pharma can sustain the goodwill.

The media and marketing blitz commenced right around the time the U.S. went into shutdown.

Pfizer fired the first volley, announcing in an April ad that “We’re taking our science and unleashing it.” Next up was Johnson & Johnson, courtesy of an eight-episode streaming series called The Road to a Vaccine. Industry trade group PhRMA followed close behind with its Doing Our Part spring campaign, which reassured any and all audiences that “science is how we get back to normal.”

While pharma hasn’t exactly been reticent on the media and marketing fronts over the last decade or three, it was nonetheless surprising to see the industry leverage this unprecedented crisis to present a more consumer-friendly version of itself. Even more surprising? That its fast, ambitious work on COVID vaccines and therapeutics seems to have burnished its reputation far better than any corporate marketing effort.

Researchers from The Harris Poll found that, as of May, 40% of the American public said pharma’s reputation had improved since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak and 81% recalled seeing or hearing something about the industry during that time. The former continued a trend that Harris first noted in March.

“It’s the biggest spike we’ve ever seen,” says Harris managing director Rob Jekielek, noting that the company has polled pharma and various other sectors since 2001. “Right now, the industry is at its highest point by multiples, in terms of both its reputation and relevance.”

When asked why their views of pharma had either become more positive or remained positive since the pandemic’s start, some 70% of this subset of Harris respondents (1,025 out of 2,026 total) said it was due in large part to the industry’s overall response to the outbreak — specifically, its efforts in developing vaccines, treatments and tests. Also cited was greater collaboration among manufacturers, which have shared data and drug formulas that might work against coronavirus symptoms. This has served to enable otherwise competitive R&D chiefs to hold regular meetings with one other.

“Those are all things that have never been seen before. They’ve never been on the radar. They’ve never even been a consideration,” says Jekielek. And, he notes, they present a more tangible way for the public to better understand the value the industry creates. “What you’re really seeing is a brand new lens on pharma companies.”

It’s a view pharma has been trying to advance for years. “I joined AstraZeneca in 2007 and my first meeting was about pricing and reputation,” recalls Tony Jewell, who left the company in 2013 to start healthcare PR consultancy Boardwalk Public Relations. “That nut still hasn’t been cracked.”

Part of the problem, Jewell says, is that in pharma, progress is largely defined by incremental change, improvements in treatments or building upon what came before — think the methodical, step-by-step progress seen in diabetes or cancer. “Rarely do you have a ‘eureka!’ moment where the industry can provide a new, effective treatment or vaccine that the world desperately needs for something that has no treatment or vaccine,” he explains. “There is a unique opportunity for the industry right now to clearly demonstrate the value it provides.”

On the other hand, Jewell doesn’t see the industry veering drastically from its PR or marketing playbooks. “The reputational improvement is people saying, ‘Hey, I see now that you don’t flick a switch and have a vaccine or a new treatment.’ This takes significant investment and time.”

Pharma isn’t the only sector that has recently enjoyed a reputation boost. Edelman’s Trust Barometer, which surveys some 13,000 people across 11 countries, shows large trust gains by the government and the food and beverage sectors.

There is a unique opportunity for the industry right now to clearly demonstrate the value it provides.

Tony Jewell, Boardwalk Public Relations

“When you think about those three areas — healthcare, food and beverage and government — for what people are experiencing right now, those are probably the sectors that they are feeling the most close contact with,” says Kirsty Graham, CEO, global public affairs at Edelman.

Another Harris study, the Essential 100, asks Americans to rank corporations playing an essential role in the pandemic. More than a few health and pharma organizations appear on the list, including CVS (ranked 10th), Johnson & Johnson (12th), Walgreens (15th), UnitedHealth Group (26th), Bayer (30th) and Anthem Health (43rd).

“You have all these companies that are getting pushed to the top of the list because it is apparent that they are delivering right now,” Jekielek says. “It’s less about aspiration and vision. It’s more about delivery.”

The results were all the more surprising given that biopharma, an industry infamous for inspiring bipartisan antipathy in Washington, DC, and long criticized for making expensive medicines and addictive painkillers, entered the year at a reputational low point. As of last September, 58% of respondents in the Gallup poll had a negative view of the industry.

With biopharma hitting rock bottom — a mere 27% of consumers had a positive view of the industry, according to Gallup, a 31% drop versus the year prior — it wasn’t hard to imagine its public perception languishing there for the foreseeable future. What followed, though, was more akin to a reputational resurrection than a requiem.

Edelman’s Trust Barometer shows the public’s trust in pharma companies rose from 58% in January to a record high of 73% in May. That represented the highest rise among the four healthcare sectors tracked, leaving it trailing only hospitals. It’s notable that pharma edged out biotech firms, whose trust levels also surged, as well as insurers.

“It’s a moment for the industry in terms of the contribution it makes and people recognizing that we’re not going to be able to get out of COVID without those contributions,” Graham explains.

But conventional wisdom suggests the numbers aren’t etched in stone. For one, reputational and trust gains have proven fickle over time. Out of 17 sectors experiencing double-digit trust gains in the Edelman survey from 2012 to 2020, 13 saw a loss in trust the very next year.

Whether pharma will sustain its trust and reputation gains depends to a large extent on the industry’s efforts over the next six months. “If there is a Hail Mary success in Q4 — particularly early in quarter four, before the U.S. election, like a vaccine and/or a near miraculous treatment — then reputation could be bolstered tremendously,” says Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, a health economist and the founder of Think-Health, a consultancy.

Barring that sort of wild card, Sarasohn-Kahn isn’t ready to read too much into the positive poll results. “There’s a phenomenon in consumer research and in history that when a crisis hits, people run to the flag, to mom and apple pie. They rally to security and what’s safe,” she explains. “Pharma was seen as a part of the solution to this crisis, and I don’t think that’s going to last.”

As to how the gains could unravel, nobody knows how long the pandemic will endure. That said, the public is increasingly looking to pharma for a way out. That puts pressure on industry to deliver soon — or else.

“The longer COVID-19 goes on and the worse the economy gets, the more people will be angry and look to blame someone,” Sarasohn-Kahn warns. “You know — ‘We’re still sick, pharma. Why can’t you get us out of this?’”

Roughly 20 million people were added to the unemployment rolls this year, many of them losing health benefits in the process. It should come as little surprise, then, that nine in 10 Americans are concerned about the price of prescription drugs, according to a June poll by Gallup and West. The pollsters found that this concern crosses political party lines and, to a large extent, household incomes. Meanwhile, among the 16% of Harris poll respondents who said their view of the industry had become more negative or remained negative since the start of the pandemic, the No. 1 reason cited was that it hadn’t made drugs more affordable in this time of crisis.

Pharma receives no free pass when it comes to drug pricing, especially when it comes to coronavirus medicines and vaccines. Consider Gilead’s June 29 announcement of what it would charge for antiviral COVID-19 therapy remdesivir.

The director of the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), a nonprofit pharmaceutical pricing group, lauded the cost as “responsible” based on current evidence. But Democratic lawmakers criticized its price tag, given that the drug was developed with the aid of taxpayer funding and is merely an off-the-shelf medicine originally intended to treat the Ebola virus. And then there’s the footnote that Gilead is expected to turn a profit on remdesivir of somewhere in the neighborhood of $1.3 billion, according to a forecast by RBC Capital Markets analyst Brian Abrahams.

The lesson Sarasohn-Kahn takes from the remdesivir episode is that pricing needs to be collaborative. Had Gilead tapped the opinion of the patient community and touted such input in its messaging, both remdesivir’s price and the market reaction to it may have been different.

That’s advice others should heed with the next COVID-19 therapy or vaccine. “The messaging could have been better in terms of contextualizing the social benefit,” Sarasohn-Kahn continues. “If you believe there’s a social benefit, tell me why. How did you get there?” Language in the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security) Act requires that products purchased by the federal government, such as vaccines and therapeutics developed using federal funds, will be acquired at a “fair and reasonable price.”

How else can industry stay in the public’s good graces? There are things it can do, beyond making good on R&D promises, to lean into innovation. For instance, the Edelman Trust Barometer detected a renewed appreciation for the doctors and scientists who work in the sector.

“People are looking for others they can trust, particularly in times of crisis when there’s worry over fake news and misinformation,” says Graham. She adds that she’s been counseling clients during the pandemic to “use your doctors and your scientists to explain what’s happening” — especially in communications around the timetable for a vaccine and the challenging process of making one.

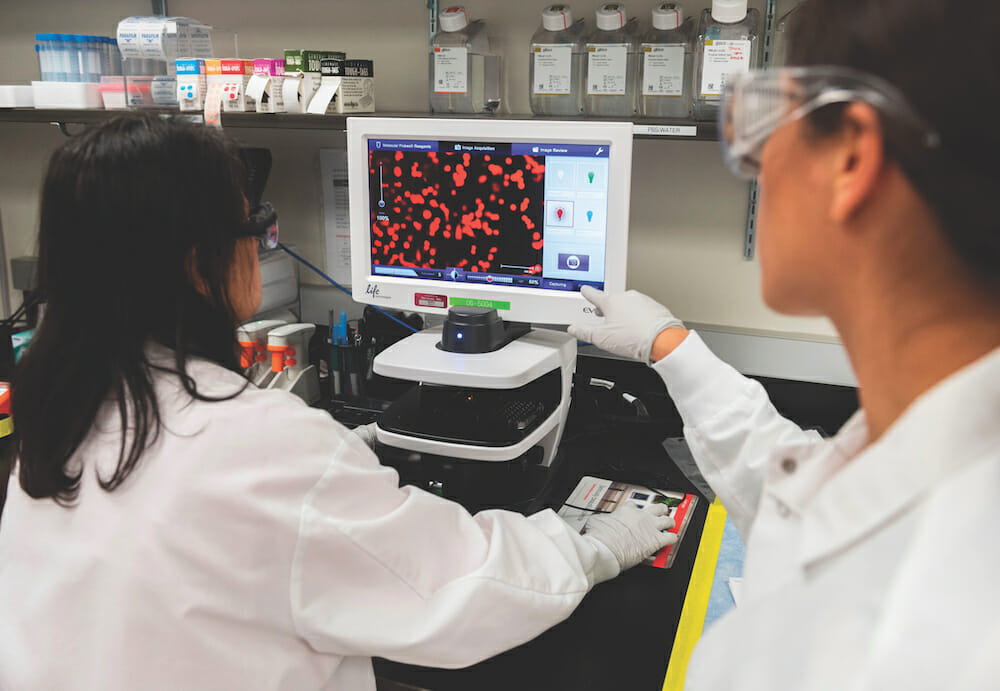

PhRMA’s director, public affairs Andrew Powaleny says the trade group will continue to showcase its researchers. “No one can tell a story about science, innovation and the everyday failures better than someone who actually sees those failures every single day in the lab,” he explains.

Indeed, pharma’s positive momentum hasn’t stemmed from “beating our chests and showing big ad campaigns,” notes GCI Health CEO Wendy Lund. “It was really about the hard work, the resources and the huge investments to solve what none of us had ever experienced before in our lives or careers,” she says, adding that the industry must keep working to “put ourselves in the forefront of what people are really thinking and what they really want.”

Graham recommends adopting the mindset of “solve, not sell” and to “think about where you show up and what conversations you have … COVID has changed the world in terms of what people care about and what people are looking to companies to do,” she explains.

For healthcare companies, one of those expectations is that they will embrace the societal need to correct glaring health inequality and access problems exacerbated by the pandemic. History will remember how they utilized their position and resources to address racial inequities and the outsized impact COVID has had on people of color.

“This commitment to broader society is something that will be with us beyond the COVID world,” Graham says.

Continued collaboration, too, will be important, across companies, disciplines and institutions as well as among the business community, civil society and government. “If one thing comes out of COVID, it is going to be an expectation — a reality — that no one’s going to be able to solve this without working with the other pieces,” Graham adds.

So how can pharma manage this new set of expectations? Even if pharma plays a major role in disappearing COVID-19 by the end of the year, don’t look for the industry’s political, regulatory or PR challenges to vanish with it, Jewell cautions.

“Hopefully there is a deeper understanding of how the industry works than there was six months ago,” he says. “The industry will always have its challenges, but it’s demonstrating right now the value that it provides to patients and society as a whole.”

From the August 01, 2020 Issue of MM+M - Medical Marketing and Media