Unprecedented in scope and size, the national COVID-19 pandemic response has penetrated nearly every corner of the country with its pro-vaccination push.

Not only have a panoply of behavioral tactics been employed, but some seemingly outside-the-box locations, like barber shops and churches, have become integral sites for public health messaging.

However, recent research published in JAMA suggests that there’s one inside-the-box venue the vaccination campaign may have overlooked: the hospital emergency department (ED).

Researchers found that implementing COVID-19 vaccine messaging in EDs led to greater acceptance of the shot and uptake in unvaccinated ED patients, many of whom were from diverse and medically underserved communities.

“We basically doubled the number of people who would accept vaccination and get vaccinated versus the control group,” said Robert Rodriguez, an ER physician at the University of California, San Francisco, and lead author on the NIH-funded study.

The results represent “the highest relative effect size of any messaging intervention published, that I’m aware of,” added Rodriguez, who led a research team spanning seven hospital EDs across four U.S. cities.

The effects were “particularly pronounced in Latinx persons and patients who lack primary care – two groups who have experienced disproportionate morbidity and mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic,” he and fellow authors wrote in JAMA.

EDs tend to be the prime healthcare hubs for the medically underserved. In the fall of 2020, during the first year of the pandemic, the researchers conducted a national study that had looked at this group and found they had less access to vaccines and higher vaccine hesitancy (between 8% and 10% were vaccine-hesitant).

“That study showed that there was going to be a big gap in vaccine availability and acceptance,” Rodriguez recalled.

With this in mind, Rodriguez and colleagues set out to determine whether COVID-19 vaccine messaging delivered in EDs could increase acceptance of the vaccine and shot rates in the unvaccinated. Based on their prior interviews with vaccine-hesitant patients in the ED, they already knew the reasons behind their reluctance and what messaging might address it.

The protocol for what would eventually become known as “Promotion of COVID-19 Va(X)ccination in the Emergency Department,” or PROCOVAXED, was written that fall. This was before the COVID-19 shots became available and certainly before any mass pro-vaccination campaigns got off the ground. PROCOVAXED was submitted to the NIH in February 2021.

The latest study launched in December 2021 and the messaging platform consisted of three components: a four-minute PSA-type video, informational flyers and scripts for face-to-face clinician messaging.

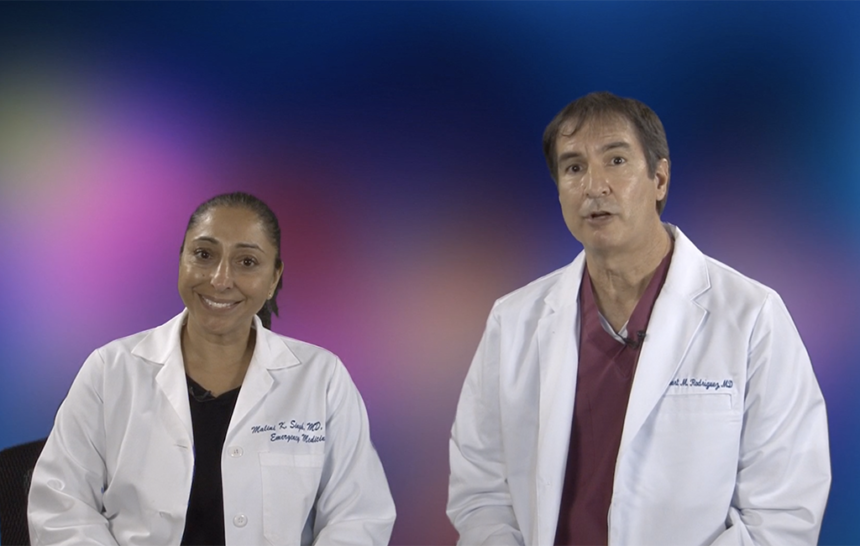

Notably, multiple versions were produced, with each version of video and flier featuring the same wording but included different physicians as the messengers or showed different clinicians administering the shot. Researchers matched them up with participants’ self-reported ethnic and racial characteristics: Latinx messengers on videos for Latinx participants, for instance.

The videos are quite basic, featuring two white-coated doctors addressing the camera in front of a generic background. Rodriguez wrote the scripts, and the hospital’s PR person worked the video camera, using a makeshift set within the facility’s library.

“They aren’t super-fancy,” he said. “What’s more important than the fluff of professional videography and all of that production is the messages and the content, in our belief.”

The videos, whose production cost was estimated to be under $1,000, and the other elements got the job done. Both rates of vaccine acceptance and uptake were higher among the group exposed to the messaging versus the control group, to a statistically significant degree.

About 12% more participants in the intervention group versus the control group said that they would accept the vaccine in the ED. That group was also about 8% more likely to wind up getting a COVID-19 vaccine within 30 days of their ED visit.

The researchers say their findings support the broad implementation of the messaging platform. They argue that the regimen could lead to greater COVID-19 vaccine delivery to underserved populations whose primary health care access occurs in EDs.

Pointing to the roughly 160 million EDs visits that took place in 2019, they estimate that an 8% to 12% increase in vaccine uptake and acceptance would lead to the delivery of “tens of thousands of COVID-19 vaccines to people who would not otherwise get vaccinated.”

“We’ve basically demonstrated that, with good content and messengers, you can have effective messaging,” Rodriguez explained.

The three messaging elements are freely available on the NIH’s open access portal. Participants viewed videos on tablets, but kiosks or televisions can also be used, or patients can view them on smartphones linked via QR codes, researchers suggested.

Can such methods make a dent in the quarter of the U.S. population that’s still unvaccinated against COVID-19? Rodriguez said he thinks so.

When the six-month trial began a little more than a year ago, COVID-19 shots had been out for almost a year, suggesting that the people who had yet to receive a vaccine by then were fairly entrenched in their views.

“We were already dealing with a pretty vaccine-resistant group, and it still worked in that population,” said Rodriguez, adding that he’d like to see similar measures enacted for the COVID bivalent booster shots.

As of last week, just 14.6% of Americans aged five and up have received the latest booster dose, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Future efforts should focus on getting shots in arms in EDs right after messaging occurs, rather than waiting or directing patients elsewhere, researchers said, given that most participants who received the COVID-19 vaccine got it during their ED visit and not at some other healthcare site.

The other principle the clinicians say their data support is that diverse populations may be more receptive to messages when they are delivered by clinicians who look and speak like them. The study population was quite diverse (62% were African American, Latinx or Native American) and medically underserved (nearly half lacked primary care and a fifth lacked health insurance).

“To address this public health delivery gap and reach a number of medically underserved populations in the U.S. (and elsewhere), you must go where they go for care: the ED,” the authors wrote.

Beyond vaccination campaigns, they say their research lays the groundwork for ED delivery of other public health measure messaging, such as for hypertension and diabetes, which could be especially helpful for those who lack access to traditional clinic-based primary care.

“We’re doing a similar study involving [ED] messaging for influenza vaccines,” said Rodriguez. “I would say that the ED as a site for public health interventions is growing. It’s not where it should be yet, but it is definitely growing.”