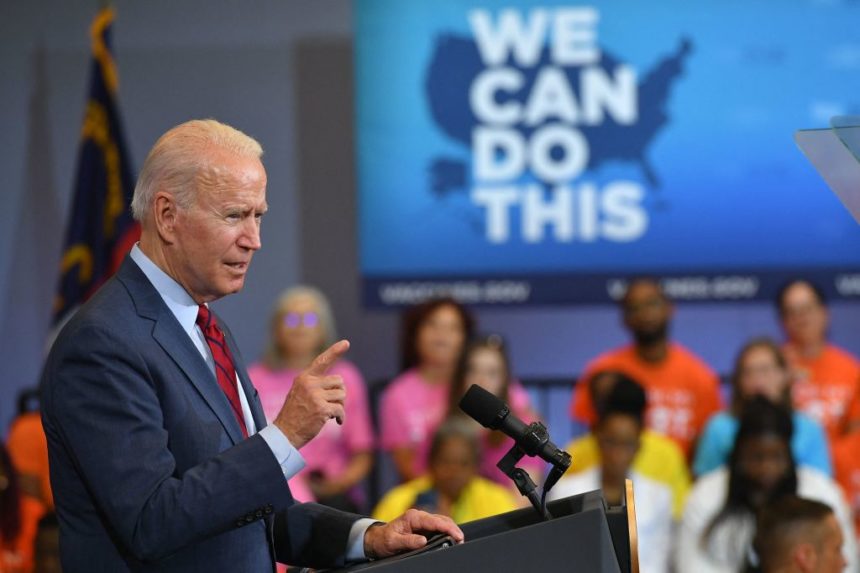

The 4th of July came and went without the U.S. meeting its goal of having 70% of Americans at least partially vaccinated. Though the country is approaching that mark, the Biden administration nonetheless finds itself scrambling to fill in the gaps across remaining pockets of the country that remain stubbornly — and, in some cases, proudly — unvaccinated.

With the final 30% so challenging to reach and/or persuade, the vaccination effort has transformed from sprint to marathon. And while a recent shift in strategy from mass vaccination efforts to localized and community-based approaches is showing promise, public health experts acknowledge that the remaining holdouts pose a huge potential headache.

“We are under no illusions that each person in this stage will take longer to reach,” one senior administration official told Politico. “The first 180 million were much easier than the next 5 million.”

The country thus finds itself in a position where vaccines are widely available and people can schedule an appointment without any hassle; supply has long since outstripped demand. That’s why Lorna Thorpe, director of the division of epidemiology in the department of population health at NYU Langone, believes the next plan of attack must be far more creative.

“That strategy of waiting for people to walk in the door is not the strategy we need now,” she explained. “We have many different groups in the U.S. who are not being vaccinated due to various concerns and hesitancies — because of some misinformation they may have received, or maybe due to barriers in their own lives. They may not have time or availability, and may need to hear from [vaccinated] people they know to overcome the concerns they may have.”

The Biden administration has thus reshaped its vaccination policy to prioritize doctor’s offices, schools, workplaces and mobile sites as the main conduits for hesitant individuals.

“‘One at a time, one conversation at a time’ is the way this is going to work,” Thorpe said.

She added that while it’s too early to assess the changes, some preliminary evidence suggest they could work. In June, vaccination rates increased more rapidly in states — including Alabama, Arizona and Florida — where community-focused strategies were being applied with the most purpose.

“Every month as we review the data and see where we are with increasing our vaccine rates, we’ll learn more about what works and what doesn’t work,” Thorpe said.

The new approach focuses on bringing vaccine doses to healthcare providers, including primary care doctors and pediatricians, who have longer-standing relationships with members of their local communities.

“The number of providers who are offering vaccines in their offices has grown significantly in the last couple of months, and that’s good,” Thorpe said. “For many health conditions, having your provider make a recommendation is a very motivating force.”

But non-traditional approaches, such as vaccine delivery via mobile vans and in pop-up clinics and workplace settings, could spur greater returns. Bringing vaccines to college campuses before the fall will similarly be integral to getting school started again, especially with virus activity likely to increase in cooler months.

In order for these localized efforts to succeed, they will require a nuanced understanding of what drives vaccine hesitancy across varied groups — whether, for instance, it is spurred by political or religious beliefs, or simply concerns about safety. Regardless of the source of the skepticism, information delivered by trusted messengers is potentially the most powerful countermeasure.

Recent data from the Kaiser Family Foundation’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor found that individuals who were hesitant to receive the vaccine earlier in the year were swayed by seeing family members receive it. That conclusion is supported by more recent data from the African American Research Collaborative, according to Real Chemistry global inclusion and health equity officer Mary Stutts.

“They found that healthcare providers, state health departments and vaccinated friends and family are the most effective messengers,” she explained. “I know many of my family members didn’t get the vaccine until after I got it and I didn’t drop dead.”

Moving forward, health experts need to lean even more heavily on the data, which will continue to shine a light on the root causes of vaccine hesitancy — and, at least in theory, suggest new ways to address it.

“That’s why the epidemiologic data around who’s becoming infected is so important, because in any particular community one needs to know: Is transmission occurring among young people?” Thorpe explained. “What are their misgivings, how can we get testing and vaccination services out there, who will they listen to, and how can we tailor our responses? It is very important to have real-time, small-area data to guide this work.”

Real Chemistry president Michele Schimmel agreed that localized approaches cannot succeed unless they are tweaked based on the most recent data. “Following the data of who people trust and what is going to motivate them is crucial to understanding who is going to take those wait-and-see-ers and move them into action,” she said.

At the core of it all, Schimmel continued, is building trust, “especially when it comes to your own life and the lives of those you love… What we’ve had to do as a public health industry is better understand what builds trust and what is leading to potential distrust, and then create programs, campaigns and spokespeople to address the nuances. It’s a very powerful emotion and a tall charge.”